Consider the range of possibilities from 4D printed materials that transform underwater, or fibers that snap into a particular shape when they are cut out of a flat panel, or coaxing shifting sands in the ocean into building artificial islands, and you will have some idea of the breadth of research that Skylar Tibbits, MIT associate professor of design research in the Department of Architecture, pursues.

Tibbits’ Self-Assembly Lab at MIT demonstrated, through studies in a water tank simulating ocean conditions, that specific geometries could generate self-organizing sand bars and beaches. To test this approach in the real world, the lab is currently conducting field experiments based on their lab work with a group called Invena in the Maldives — a chain of islands, or atolls, in the Indian Ocean, many of which are at risk of erosion and, at worst, submersion from rising sea levels.

Wind and waves naturally build up sand bars in the ocean environment and just as naturally sweep them away. The idea of the Maldives project is to harness the power of waves and their interaction with specifically placed underwater bladders to promote sand accumulation where it is most needed to protect shorefronts from flooding, rather than building land-based barriers that are inevitably worn away or overwhelmed.

Sand alone may not ensure permanency to these “directed” islands, so the Self-Assembly Lab hopes to incorporate vegetation into future efforts, drawing on classic motifs of landscape engineering such as mangrove forests that anchor an ecosystem. “In the bladders underwater, you could seed them with vegetation to make them stay,” Tibbits said in a presentation to the MIT Industrial Liaison Program’s Research and Development Conference on Nov. 13.

Tibbits also discussed his collaborations on “4D printing,” objects that are formed by multi-material 3D printing but designed to transform over time, whether that transformation is activated by mechanical stress, water absorption, light exposure, or some other mechanism. One method to create adaptable materials is by pairing two different materials that expand or contract at different rates. In a collaboration with Stratasys and Autodesk, he designed a single strand of material that, as soon as it is immersed in water, folds itself into the letters M - I - T.

Working with BMW, the Self-Assembly Lab designed silicone cushion clusters that are 3D-printed in liquid and can be inflated cell by cell, thus changing their overall shape, stiffness, or movement. This material could be the basis for more comfortable seating that adjusts to individual passengers.

The Self-Assembly Lab is conducting active textile research in collaboration with Ministry of Supply, fiber extrusion specialty firm Hills Inc., the University of Maine, and Iowa State University. So far, the group has produced sweater yarns that can be heated to conform to an individual wearer’s body shape, with a long-term goal of producing climate-adaptive textiles. This work is partly funded by Advanced Functional Fabrics of America, and that portion of the research is administered through the Materials Research Laboratory.

The Self-Assembly Lab also developed a method to 3D-print liquid metal into powder that creates fully formed parts that can be lifted out of the powder. The parts are made of a material that can be re-melted to form new parts.

Using carbon-based materials in a project for Airbus, the Self-Assembly Lab developed thin blades that can fold and curl by themselves to control the airflow to the engine. The “programmable” carbon work was carried out with Carbitex LLC, Autodesk, and MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms.

For a chair project with Biesse and Wood-Skin, the Self-Assembly Lab designed a small table that marries 3D-printed wood fiber panels and pre-stressed textiles. The table can be shipped flat, then jump into several different arrangements because of the flexibility of the textile.

By 3D-printing a stiffer material in a circular pattern onto a flat mesh, for example, the researchers showed that cutting out the circle from the flat plane causes it to snap into a hyperbolic parabola shape. The researchers include MIT computer science Professor Erik Demaine; Christophe Guberan, a visiting product designer from Switzerland; and David Costanza MA ’13, SM ’15.

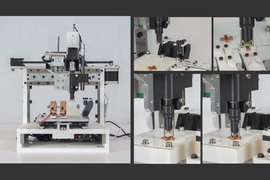

Tibbits worked with Steelcase to develop a process for 3D printing plastic into liquid for furniture parts, called rapid liquid printing. This process prints within a gel bath to provide support for the printed parts and minimize the effect of gravity. With this printing technique they can print centimeter- to meter-scale parts in minutes to hours with a range of high-quality industrial materials like silicone rubber, polyurethane, and acrylics.

The common theme across all these different projects is Tibbits’ belief that the future of industrial production lies in the transformative power of harnessing smart, programmable materials. “We want to think about what’s coming next and see if we can really lead that,” Tibbits says.