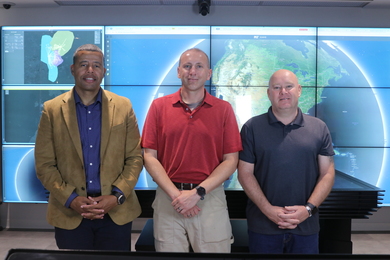

Spider webs were making music in Paris this fall, at MIT visiting artist Tomás Saraceno’s Palais de Tokyo art exhibit, ON AIR. "Spider’s Canvas," an exploration that sonifies the threads of a spider web, was designed, constructed, and performed by MIT’s Center for Art, Science, and Technology (CAST) Faculty Director and Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor Evan Ziporyn, Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) PhD student Isabelle Su, CEE department head and McAfee Professor of Engineering Markus Buehler, MIT Music and Theatre Arts lecturer Ian Hattwick, and composer and video artist Christine Southworth ’02.

Based on research on spider webs from MIT’s Laboratory for Atomistic and Molecular Mechanics (LAMM), Su, Buehler, and Ziporyn produced an interactive instrument that echoes the parallels of music and materials science.

ON AIR combined material from scientific institutions such as MIT, research groups, activists, and philosophers, to examine how human activity impacts the environment and various systems. The collaboration between CEE and CAST reflects the many ways in which music and science intersect. The 3-D spider web itself is a network that portrays this intersection, visually and acoustically embodying the unification of several disciplines.

“'Spider’s Canvas' is truly the most collaborative project I’ve ever been involved in. It’s not just interdisciplinary but literally interspecies. The real ‘first mover’ was the spider herself. In performance, all four humans have an equal effect on everything the audience sees and hears,” says Ziporyn.

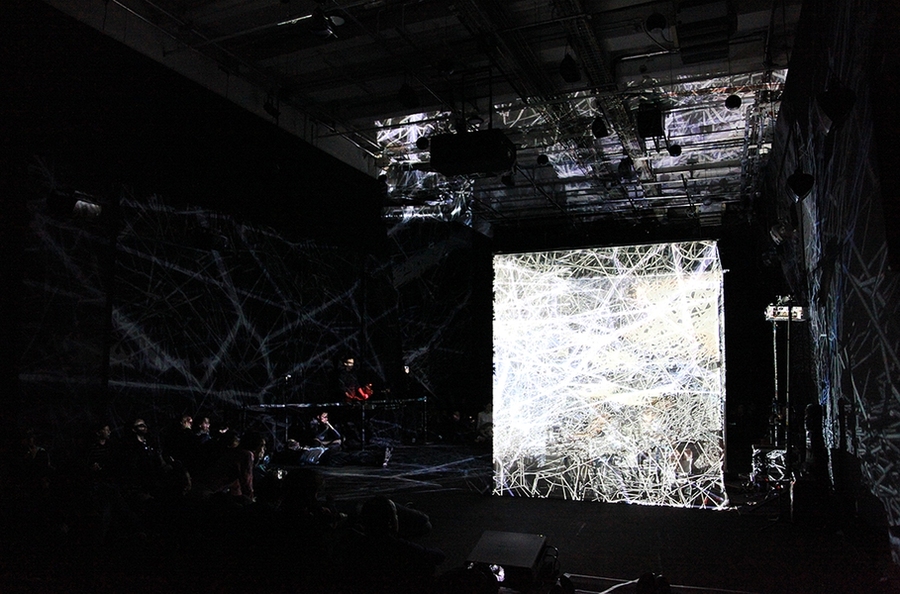

Creating an immersive performance

The project is based on a spider web which was spun by a Cyrtophora citricola spider. Buehler, Su and Saraceno created the spider web topology using automatic laser scanning and image processing protocols.

“Spider webs are intricate material systems that feature hierarchical structures that range from the chemistry of proteins to the complex architecture of filaments in the web, whereas this complexity is built from simple building blocks,” says Buehler. “Similarly, in music, sound is generated by the assembly of elementary units to produce complex harmonies and rhythms. In this project we’ve demonstrated an intimate connection between these realizations of complex systems.” Obscuring the distinction between what is material and what is sound, the spider web instrument allows researchers to interact with and immerse themselves inside the web.

To create the sonification of spider webs, the team applied different frequencies of sound to several different lengths of spider web fibers.

The researchers thought about acoustical concepts starting from sine waves, the simplest form of sound production. Sine waves are defined as the mathematical waveforms that describe periodic oscillations. The group then combined different sine waves to create more complex sounds, reflecting the tiered structure of music.

Analogous to music, spider silk has a hierarchical organization and functions that are comparable to Western classical music of the 18th and 19th century. The team compared the protein secondary structure and stable structure of silk to musical notes and chords.

By drawing upon this analogy between music and silk, which both rely on limited simple building blocks, the group has intentions of ultimately creating and improving material designs.

Buehler’s lab’s research on spider webs goes hand-in-hand with the work of Saraceno’s spider-web-based art and his ongoing collaboration with MIT, which provided the foundation of the sonic structure for "Spider’s Canvas." As the parallels of science and music became evident, it inspired a new set of ideas that pushed the boundaries of the project.

“The goals in art can often be very different than the goals in research; however, they share a similar methodology,” Ziporyn says.

Attaining a new perspective on the project, the team began layering various elements to the spider web sonification. Their goal was to create a holistic and immersive experience for the audience. Using the coding systems Unity and Max/MSP, they created an interactive video game within the spider web. While traveling throughout the web, the participants can decide the speed, what they look at, and, therefore, what they listen to.

“This visualization method paired with the generation of sound creates a more complete and holistic experience,” Su explains.

During the performance, Su controls what the audience views, as if it is coming from the spider’s perspective. While she guides the viewers through the web, the different types of fibers they see reflects what the audience hears.

Ziporyn describes the experience of performing "Spider’s Canvas" in holistic terms: “This piece makes you feel that connection between the physical world and the acoustic world; your senses are aligned and focused, allowing you to experience it and pay attention to it in your body and in your spirit.”

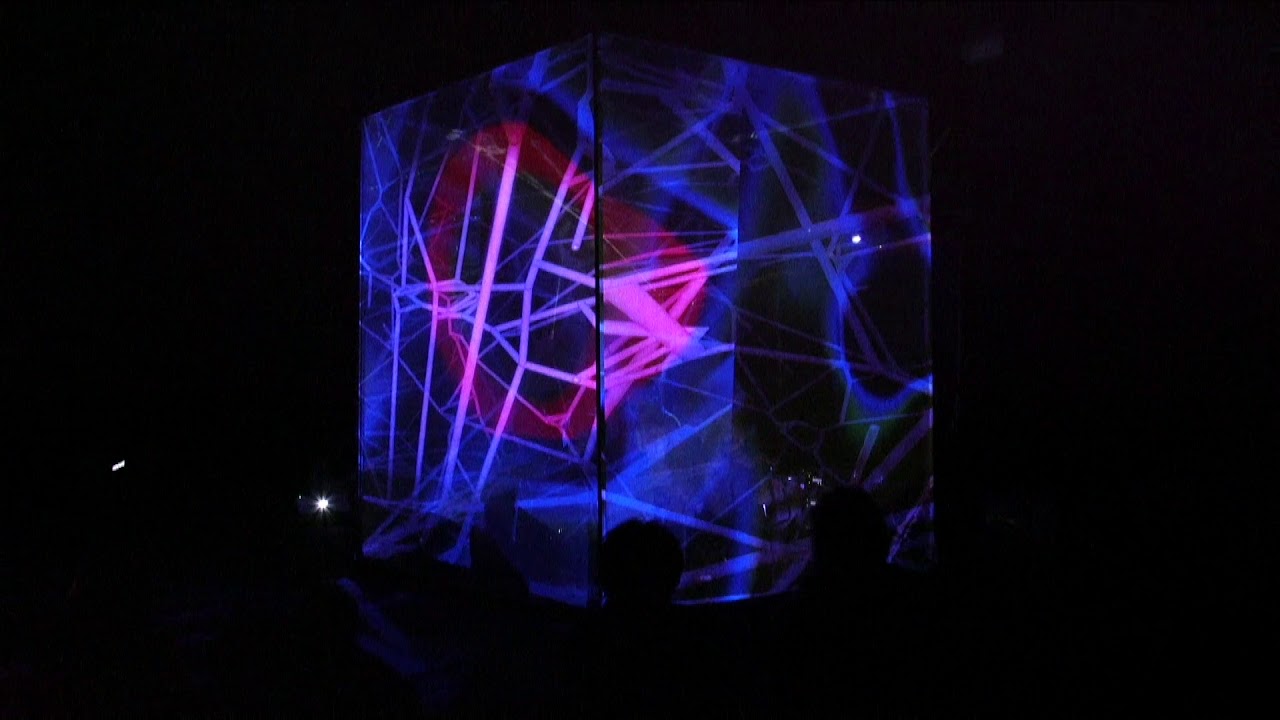

Southworth, a composer, added another element to "Spider’s Canvas" by improvising with the electric guitar and creating projections that amplified the intricacies of spider webs.

“It’s an autonomous improvising structure,” says Ziporyn. During the concert, “The ‘driver,’ Su, improvises by where she drives us; Ian improvises by how he sculpts the sounds the web is generating; and Christine and I improvise on top of it.”

Furthermore, the team was interested in the ways they could communicate the similarities between music and science through various mediums that would engage the audience’s senses and create a captivating concert.

MIT Music and Theatre Arts lecturer, Ian Hattwick, worked on the 3-D spider web project by taking what the researchers had already developed and adjusted it from an aesthetic sonification standpoint, including how it would work with other acoustical elements of the performance.

The concert was truly mesmerizing, according to Hattwick. “We had ourselves within the spider web and we were making immersive sound that was distributed around the room. People found themselves in the middle of the sound, the web, and the room.”

Merging science and art

Saraceno’s work is based upon literature from the science and technology movement, and focuses on the idea of networks. Placed within the context of the art exhibit, the performance of "Spider’s Canvas" was a metaphor within itself.

The project exemplifies the concept that Su, Hattwick, Ziporyn, and Southworth were dependent upon each other, similar to the way in which spider webs are intertwined and reliant on the environment they exist in. Spider webs are strategically constructed in order to continue the cycle of catching food and breaking it down in order to create the silk fiber necessary to spin their web once again.

“We are part of this interconnected network no matter what we do. Our actions will always have effects outside of ourselves and similarly, we are also affected by external factors,” says Hattwick.

Each node of a spider web, or each individual, contributes to a larger ecosystem of knowledge and ideas. This multifaceted 3-D web is not only based upon concrete scientific data, however; it also embodies the larger concept that humans need to transcend various disciplines in order to create and innovate.

“Just as Tomás’ exhibit is focused around the idea of interconnectedness, so is this project. In itself, there are various moving parts and people who come together with strong backgrounds and knowledge that allow it to manifest in such an immersive and complete way,” Hattwick says.

The interdisciplinary culture at MIT allowed the team to take concrete data of 3-D spider webs and convert it into an intricate harmony, a sensation, and an experience. The group is optimistic that the project will challenge others to take on similar endeavors and become part of the conversation, whether that may be from an artistic perspective or on the research level.

“Working on collaborative projects within a culture such as MIT is great because we are encouraged to explore unfamiliar areas, outside of our research. Our goal is to think about how what we do fits into the larger discipline and the larger discourse,” explains Hattwick.

The researchers are enthusiastic about the concept of creating an even more immersive experience. They plan to design virtual reality glasses that would create the illusion that users are traveling inside of the spider web. In addition, they hope to incorporate physics into the game, which would allow users to pluck any spider web fiber, and feel it vibrate throughout the web.

“The concert was really incredible. I am grateful for this experience and would love to continue working with MIT CAST,” says Su.

“Our study of the way function emerges in a material (such as its strength or deformability), and how function emerges from sound (such as the way music can stimulate our brain and body), can lead to new insights that can benefit both the inspiration of new art and the development of new technology, as we increase our ability to cut across disciplines. Working with this incredible team from many corners at MIT has been a rewarding experience,” says Buehler.

Spider’s Canvas will be performed Feb. 16-18, 2019 at the W97 Main Theater. Visit sounding.mit.edu for more information.