When Takian Fakhrul was a young girl, her father, then a graduate student in materials science at the University of Manchester, would bring her along to his lab. During these visits, she would peek at structures under the microscopes or watch him polish newly synthesized materials. And she just couldn’t seem to stay silent.

“I used to ask a lot of questions,” says Fakhrul, who is now a fourth-year PhD student in MIT's Department of Materials Science and Engineering. “My dad tells me that I was a super-curious child.”

Fakhrul’s curiosity blossomed further when she was an undergraduate at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology in her hometown of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Conversations with her father, who was then a materials science professor there, figured heavily into her decision to major in the same field. They talked about pressing scientific problems, like the limits of existing materials and breakthroughs in materials science that could “really affect the future of technology,” Fakhrul recalls.

Now, working in the lab of Caroline Ross, the Toyota Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Fakhrul researches how garnets can solve problems in photonics, the study of the technical applications of light.

After finishing her PhD, she plans to return to Bangladesh to teach materials science and mentor students who want to pursue graduate studies. She hopes to help advance the field in her home country, drawing from some of the ingenuity she’s observed at MIT and at Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, where her colleagues have found creative ways to conduct their materials science research despite having far fewer resources. “I’ll take back my expertise, the connections I make here, and hopefully I’ll be able to create a bridge between MIT and Bangladesh,” she says.

Breaking speed limits

Within computers, data moves between and within chips electronically through small copper wires. In an increasingly technology-dominated world, “computers need to work faster and faster,” Fakhrul says. In order to do that, scientists must design chips and connections that allow faster data transfers and lower power consumption.

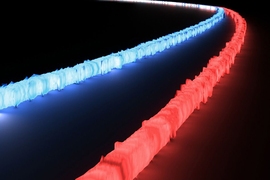

“The problem is that there’s a limit to the speed of electrons passing through metal wires,” Fakhrul says. “What’s faster than electrons in metal? The answer to that is light.” And, unlike metal wires, which can carry only a single electronic data stream, optical fibers can carry multiple wavelengths of light — and thus multiple data streams and more bandwidth — without interference. Optical fibers are already being used in networking and storage area networks; the key to advanced optical communication, and maybe even computing with light, is to design fast and energy-efficient optical fiber interconnects that function well on silicon chips.

Fakhrul researches materials for optical isolators — a component of lasers used in silicon photonics that provide a one-way path through which light can travel. “It lets light pass in the forward direction, but not backward. And that’s extremely important,” Fakhrul says. “Back reflections going into the laser destabilize the laser, reducing its performance.”

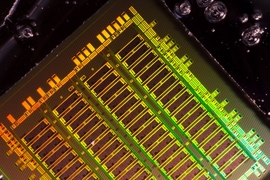

“If you really want to integrate silicon photonics onto a chip, then you definitely need to have this optical isolator integrated as well,” Fakhrul says.

Fakhrul focuses on iron garnets, which often experience chemical substitution — a trait that gives materials scientists the opportunity to design new variations of the material. The transparent nature of garnet allows light to pass through without interference. Iron garnets are also magnetic, such that they can rotate the plane of polarization of the light as it travels through. “When light passes through garnet, it acts differently in one direction than in the other direction,” Fakhrul says. By manipulating the garnets to design one-way streets for light, she hopes to demonstrate that garnets are the ideal materials for integrated optical isolators. But they also come with a catch.

“[Garnets are] actually very difficult to integrate on silicon,” Fakhrul says. “So that’s something that materials scientists have to deal with and figure out.”

Fakhrul is also interested in how garnets could be used to improve information processing. In an emerging field known as magnonics, information is transferred via the collective precession of spin waves — disturbances that propagate through magnetic materials. In garnets, spin waves “travel for long distances without relaxing,” Fakhrul says, due to their low damping constants.

“You can have this one class of materials, but then it has these unique properties that make it interesting for these versatile applications,” Fakhrul says.

Cherishing community

After earning her undergraduate degree, Fakhrul was hired as a lecturer at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology and began to teach other materials science students while she completed her master’s in materials science.

During her master’s program, she also married her colleague, Nadim Chowdhury, who was a lecturer in electrical engineering and, like Fakhrul, planning to pursue a PhD.

A month into their marriage, Fakhrul recalls, “I got my acceptance letter from MIT, and he got his acceptance letter from Princeton. We were really thinking about long-distance. But a week later, he got into MIT as well! It was so amazing — it was like a miracle,” Fakhrul says.

Together, Fakhrul and her husband moved to Cambridge, and they began their studies at MIT. To stay in touch with her cultural heritage, Fakhrul became involved in the Bangladeshi Students Association at MIT, which hosts events with national, cultural, and religious significance throughout the year. This year, Fakhrul will be a co-president of the student group after working as a secretary for two years and an organization chair for one.

Promoting research

Fakhrul ultimately plans to return to Dhaka and continue teaching materials science. But she also has an additional goal: to help advance materials science research back home.

During her third year at MIT, Fakhrul attended the IEEE Magnetics Society Summer School — a school for approximately 85 graduate students from around the world studying magnetism, held in Spain. A winning entry in a group project competition gave Fakhrul the opportunity to travel to the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi to visit some of their research labs.

“What I really took back from my visit to IIT Delhi is how creative people can be when they have such limited resources,” Fakhrul says. She cites the availability of instrumentation for materials science research: What may be readily available and easy to order at MIT might be challenging to acquire in Dhaka or Delhi.

“[At IIT Delhi], they had a lot of parts made from local suppliers, and then they imported other parts, and then made a whole thin-film deposition system. It was at least three to four times cheaper. I thought that was really incredible because that’s something I would want to do once I go back to Bangladesh,” Fakhrul says.

Fakhrul actively works with students at her alma mater as a mentor, and hopes to continue that after returning home as well.

“Whenever I get some time off from work, I also like helping students in Bangladesh apply [to graduate programs in the United States],” she says. In total, Fakhrul mentors 10 students, six of whom are currently pursuing PhDs in the United States. At the start of the 2018-19 academic year, one of her mentees began his graduate studies at MIT.

“The feeling was so incredible, because I was the first person from materials science from my school to come here,” Fakhrul says. “It’s really nice when you get to help other people make their dreams come true as well.”