Whether it’s the pleasant experience of returning one’s childhood home over the holidays or the unease of revisiting a site that proved unpleasant, we often find that when we return to a context where an episode first happened, specific and vivid memories can come flooding back. In a new study in the journal Neuron, scientists from the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT are reporting the discovery of a mechanism the brain may be employing to make that phenomenon occur.

“Suppose you are driving home in the evening and encounter a beautiful orange twilight in the sky, which reminds you of the great vacation you had a few summers ago at a Caribbean island,” says study senior author Susumu Tonegawa, the Picower Professor of Biology and Neuroscience at MIT. “This initial recall could be a general recall of the vacation. But moments later, you may get reminded of details of some specific events or situations that took place during the vacation which you had not been thinking about.”

At the heart of that second stage of recall, where specific details are suddenly vividly available, is a change in the electrical excitability of what researchers call “engram cells” — the ensemble of neurons that together encode a memory through the specific pattern of their connection. In the new study, Tonegawa’s lab — led by postdoc Michele Pignatelli and former member Tomás Ryan, now of Trinity College in Dublin — showed that after mice formed a memory in a context, the engram cells encoding that memory in a brain region called the hippocampus would temporarily become much more electrically excitable if the mice were placed back in the same context again. For instance, if they were given a small shock in a specific context one day, the engram cells would be much more excitable for about an hour after they were put back in that same context the next day.

The researchers say the specific change in the engram cells’ electrical properties has some direct implications for learning and behavior that hadn’t been appreciated before. Importantly, during that hour after returning to the initial context, because of the engrams’ elevated excitability, mice proved better able to learn from a shock in that context and better able to distinguish between that and distinct contexts even if they shared some similar cues. The increase in excitability therefore allowed them both to learn to avoid places where danger happened very recently and to continue to function normally in places that happen to have some irrelevant resemblance. And because the effect was short-lived, it didn’t oblige them to remain overly attuned for very long.

“The short-term reactivation increases the future recognition capability of specific cues,” Pignatelli and Tonegawa’s team wrote. “Engram cell excitability may be crucial for survival by facilitating rapid adaptive behavior without permanently altering the fundamental nature of the long-term engram.”

Tonegawa adds that “while the survival interpretation may be an evolutionary origin of this multi-step episodic memory recall” it likely also applies to positive episodic memories, like the vacation sunset experience, just as much.

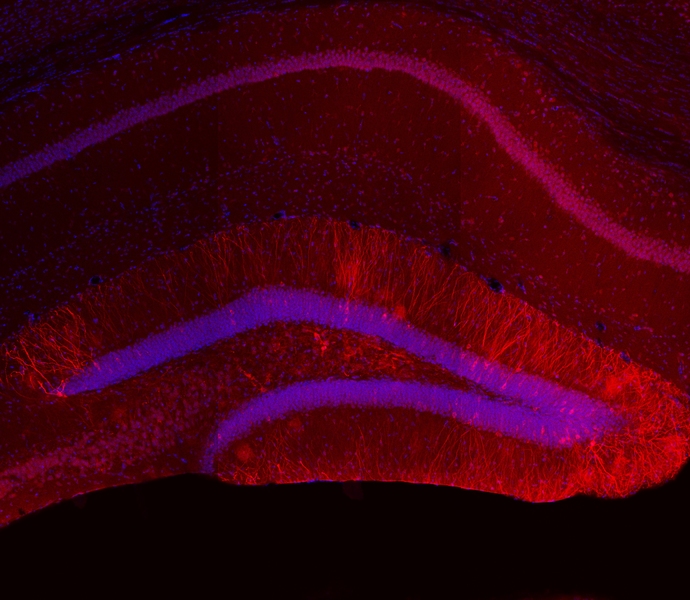

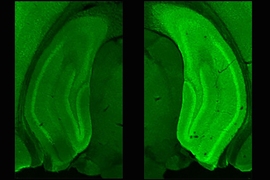

Using methods they’ve devised to label specific engrams, the team initially explored what happens when mice are returned to the context where they previously formed a new memory. They found that five minutes after mice were re-exposed to the context, the engram cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus were more electrically excitable than in mice who had been re-exposed three hours before or in mice who weren’t re-exposed at all. Subsequent experiments showed that the added excitability lasted for an hour after re-exposure before dwindling to no difference by two hours.

The finding prompted the scientists to investigate what accounted for the change. Their examination of the engram cells revealed that when they were more excitable, they expressed fewer of what the researchers call “inward rectifier” channels for potassium ions on their surface. Meanwhile, if they chemically interfered with protein synthesis, they found they could prevent the excitability from returning back to normal levels after an hour. Also, if they induced extra surface expression of the ion channels, they prevented re-exposure to a context from increasing excitability.

Taken together, their findings suggested that reduced expression of the potassium ion channels causes the excitability increase and protein synthesis ends it, after about an hour.

To understand the implications of the extra excitement on behavior, the team performed experiments that tested its effect on two main strategies of memory recall: pattern separation, in which the brain distinguishes between cues, and pattern completion, in which the brain extrapolates from available cues.

To test separation, they first trained the mice by giving them a little shock while in a specific place (which they called Context A). They next day they re-exposed two groups of mice to Context A — to increase engram excitability — but left a third group out of Context A as a control. The next day, they exposed all the mice to a new context that shared some of A’s cues but also had other ones (which they called Context AB). Some of the mice that had been returned to Context A entered Context AB after five minutes, while others entered after three hours.

So what happened? The mice who didn’t go back to A at all and the mice who had three hours between A and AB each froze up in fear in AB, as if they couldn’t be sure they weren’t back in A, where they had experienced a shock the day before. The mice who went to AB only five minutes after being in A didn’t freeze up in AB. Well within their hour of elevated engram excitability, they could tell the difference between A and AB.

On the first day of the pattern completion test, the researchers gave three different groups of mice about 10 minutes to explore a new Context A. They next day they returned all three groups to A. The control group got a little shock and were removed immediately. The second and third groups then each got to spend 3 minutes re-exploring A. The second group then returned again five minutes later for a mild shock and the third group returned three hours later to get a shock.

On day 3 all three groups were returned to Context A. The control mice and the ones who received the shock three hours after re-exposure each were much less likely to freeze in fear than the mice who got their shock within five minutes of re-exposure. They were clearly more attuned to being back in A.

The scientists hypothesize that the way enhanced excitability sharpens memory is by making the engram cells more sensitive to lower levels of input from their connections with other neurons, or synapses. In the broader circuits that connect memory and behavior, they are relays that can act even with less information.

“The excitability increase in the engram cell is likely to compensate for the reduction of synaptic inputs due to limited cue availability,” they wrote.

In addition to Pignatelli and Tonegawa, the paper’s other authors are Tomas Ryan, Dheeraj Roy, Chanel Lovett, Lillian Smith, and Shruti Muralidhar. The RIKEN Brain Science Institute, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the JPB Foundation funded the study.