For MIT Assistant Professor Azra Akšamija, many of today’s headlines resonate both personally and professionally. Born in Sarajevo, Akšamija and her family fled Bosnia from the war in in 1992, when she was 14. She then moved among European countries and the United States as a Muslim immigrant pursuing her education and her art.

Today, through a multidisciplinary practice in art and architecture, Akšamija focuses on the representation of Islam in the West, spatial mediation of identity politics, and cultural transfers through art and architecture. Her work explores and blurs the boundaries between identities, such as her “wearable mosques” — including a traditional Austrian dirndl dress that transforms into an Islamic prayer environment — or her architectural design for a prayer space at the award-winning Islamic Cemetery in Altach, Austria, constructed of local materials in the manner of regional craft traditions while drawing upon motifs of Islamic religious architecture.

Akšamija, the Class of 1922 Career Development Professor in the Department of Architecture and assistant professor in the Program in Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT), spoke with the School of Architecture and Planning about her life and work and her perspective on the intersection of culture, religion, and politics.

Q: You create work that grapples with representations — and misrepresentations — of religious and cultural identity, including how Islamic identities are framed in the West. What first drew you to these topics as an artist?

A: Personal history. I come from Sarajevo, Bosnia, a place historically known as the Jerusalem of Europe. I grew up in an environment where many different cultures and religions coexisted for centuries. Historically, that coexistence was fruitful, and you can see this in the rich and diverse cultural heritage of the Balkans. That certainly informed my life and my family's views. The war in the Balkans in the 1990s instrumentalized this cultural and religious diversity for political ends, and that affected my artistic and intellectual trajectory from then on.

I have been living outside of my hometown from the 1990s onward, when we fled Bosnia — first to Germany, then to Austria. I have also lived in other countries throughout Western Europe, and then finally moved to the United States for graduate school in 2002. On the one hand, the experience of a migrant’s life allowed me to feel at home in many different places, and these new cultures shaped me in a very positive sense. On the other hand, being a Muslim from Central Europe has exposed me to certain problems of perception and misrepresentation in Western Europe and the United States, where I was often put in a position of having to justify my identity, or defend something that my culture stands for.

Through my research I came to understand that culture was completely instrumental in dividing a society. In Bosnia, I documented the systematic targeting of religious buildings, and culturally and ethnically significant sites, and analyzed how this cultural warfare enforced division of a multiethnic society. There was a certain sadism against architecture and culture that was meant to ultimately humiliate and intimidate people — using cultural instruments to prevent people from wanting to live together in the future.

Culture and art go hand-in-hand with politics, as I learned from the war in Bosnia, and this is where I discovered for the first time the power of culture. If culture was so powerful in the hands of nationalist extremists who wanted to transform Bosnia's multiethnic society into ethnically homogenous, separated, and mutually hostile nationalist enclaves, then we can also work with cultural means against these kinds of developments. This is what I’m trying to do in my work.

Q: The portrayal of Muslims in the United States has recently included calls for registering Muslims or barring them from entering the country. What is your reaction to how these issues are being framed?

A: If we learned one thing from the Second World War, it’s that there can be a frightening trajectory when this kind of rhetoric is used. Politicians exploiting hate speech and populist rhetoric need to be held accountable, and the media has a big responsibility in giving a voice — a differentiated voice — to other kinds of representations. In the current debates, what’s very problematic is that opinions get polarized into either/or categories. What we really need more of in the media is another, multilayered perspective on Islamic culture, one that is not exclusively linked to violence and war.

At MIT, for example, we can shed light on Islamic civilization’s contribution to the sciences. So much of the knowledge we are building on today is based on the achievements of Islamic scientists from the past. And contemporary Islamic societies aren’t stuck in the past. There are incredible scientific and cultural achievements — of people affiliated with Islamic civilization who may be either secular or religious — happening in the Middle East or the United States that could be reported on.

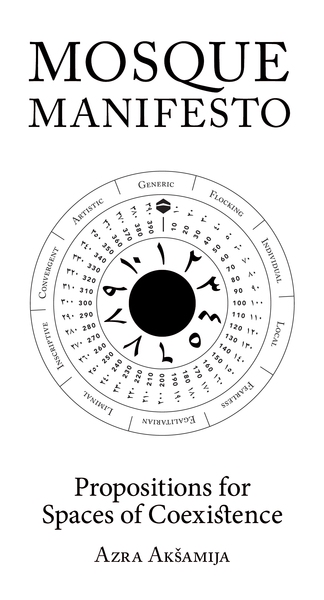

There’s also something that art can do, and that’s why I titled my book "Mosque Manifesto: Propositions for Spaces of Coexistence." I’m not directly engaging these political debates with defensive or offensive statements, but rather expanding the vocabulary of representation through alternative forms of religious architecture. There is this amazing opportunity to design mosques today with a language that appeals to Muslims in different contexts, but also to their non-Muslim neighbors for functions that could be both Islamic and non-Islamic.

What I’m trying to do is offer a new aesthetic while moving beyond the iconic language. I work on a sensory level and human scale to communicate and move people, which is something that art, architecture, and culture can do.

Q: It seems as though art that touches upon these issues could be challenging. How do people respond to your work?

A: I’ve had wonderful feedback, especially from the young Muslim community. People see themselves in [the art], as some of these pieces are empathetic. They speak to both Muslims and non-Muslims.

My work has been presented and exhibited in Islamic as well as non-Islamic contexts. In the United Arab Emirates, for example, my work has challenged the established norms of gender segregation, revealing how tradition is malleable and constantly reinvented. In the United States, I created the "Survival Mosque," giving form to experiences about how it felt to be a Muslim in America after September 11.

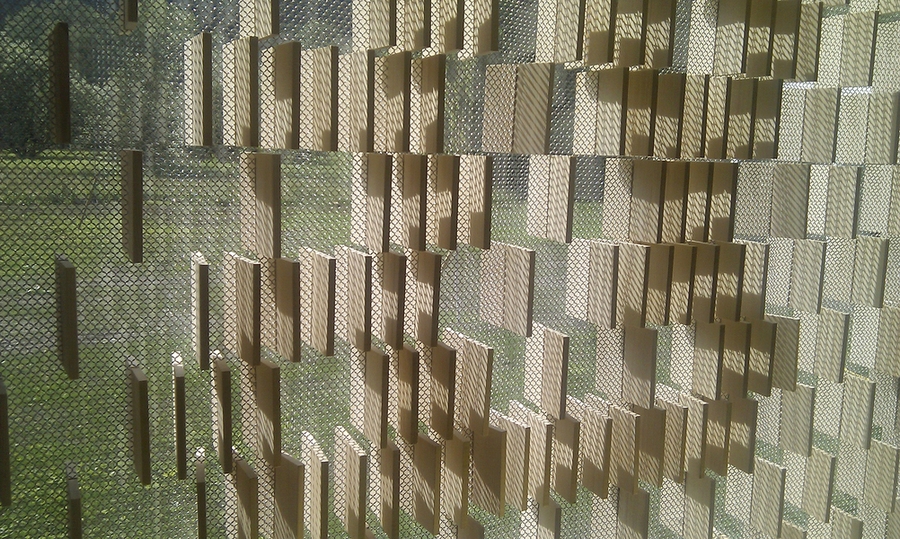

In Austria and Germany, Jewish museums have been defending the interests of Muslim minorities. Because of their own history in Europe, they understand these concerns. I think some of my pieces, like the Jewish/Muslim hybrid called "Frontier Vest" or the "Shingle Mihrab," speak to the Jewish and Christian communities too, because they introduce the idea of coexistence, the possibility of cultural hybridization, and the simultaneous belonging to different places.

When I exhibit my work, it’s interesting to see how the curator or venue chooses to describe me, depending on what they need and what kind of message they want to communicate. Sometimes I'll be an “Austrian artist.” Sometimes I’ll be a “Bosnian-born artist,” sometimes I’m a “Muslim woman artist.” I often joke that I’m a Sarajevo-born, Austrian Muslim, living and working in Cambridge, but with a global practice, and working across disciplines of art, architecture, design, and history.

How do you even express the entirety of your own persona? The bottom line is: We are all humans, and we can relate to each other on the level of our humanity.