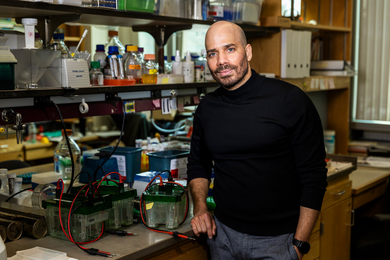

In Song Kim was raised with an appreciation for the importance of closely tracking international relations. His grandfather was a Korean politician who lived through the Japanese occupation and World War II. He taught his family that the fate of small countries is often determined by negotiations among the big powers. Kim set his sights on having a role in international decision-making as a bureaucrat at the UN or World Bank, and he earned a master’s degree in law and diplomacy from Tufts University's renowned The Fletcher School.

But Kim, who joins the MIT Department of Political Science as an assistant professor in the fall of 2014, stopped short of the negotiating table when he found himself more interested in the theory of international relations than its practice. He wanted to understand why countries have difficulty coming to agreement. Kim’s attention was drawn to this bit of conventional wisdom among political scientists: Trade policy reflects conflicting political interests at the level of industries. But when he looked at the data, he saw examples that ran counter to the conventional wisdom. “Government actually sets trade policy very differently across very similar products within the same industry,” he says.

Kim devoted his doctoral research at Princeton University to probing trade policy at the level of products. His thesis, "Political Cleavages within Industry: Firm-level Lobbying for Trade Liberalization," won Best Paper Award at the 2013 International Political Economy Society conference. But when he began his research, he quickly ran into a problem: There was a lot of data. He needed to examine trade relations between pairs of countries for specific products. He was looking at monthly trade volumes for more than 200 countries and tens of thousands of products. “Big data not only means that you have a larger number of data sets, it also means that you have different computational and methodological challenges to solve,” he says.

Kim adapted the tools of the natural sciences — cluster computing and data analytics algorithms — to the task of analyzing product-level trade relations. “I’ve done a lot of programming so that I can actually deal with the data,” he says. “My research has focused more on developing proper methodology to analyze data.”

Using his big data tools, Kim found an interesting pattern. The way firms lobby government on trade policy — pushing for more protectionism or more liberalization — depends on how unique their products are. The more differentiated a company’s products, the more likely it is to push for lower tariffs or other forms of trade liberalization. And when a company’s products are not very differentiated, meaning the products can more easily be replaced by other, potentially less expensive products, the company is more likely to push for higher tariffs or other forms of protectionism.

Not only is product differentiation the key factor, product differentiation varies within industries. For example, some automobiles are relatively replaceable, and some textiles are relatively unique. In addition, firms that produce highly differentiated products tend to be larger and wield greater influence when lobbying. “They’re not only economically powerful, but also politically powerful,” says Kim. “It is the productive, big firms that are actually important in driving trade policy, especially for the countries that are producing differentiated products,” he says.

Looking ahead, Kim plans to extend his research to predictive analytics, which is the branch of big data that makes it possible to anticipate trends. “Once you know some recurring patterns, then you can actually predict what is going to happen,” he says.

For Kim, MIT is the ideal place to do this work. “My research really lies between economics, political science, and computer science,” he says. Computer science can advance political science, and political science and the other social sciences can help computer science students shape and apply their skills. “That’s why I’m very excited to be part of the MIT community.”