Economists often talk about “moral hazard,” the idea that people’s behavior changes in the presence of insurance. In finance, for instance, investors may take more risks if they know they will be bailed out, the subject of ongoing political controversy.

When it comes to health insurance, the existence of moral hazard is a more matter-of-fact issue: When people get health insurance, they use more medical care, as shown by research including a recent randomized study on the impact of Medicaid, which MIT economist Amy Finkelstein helped lead.

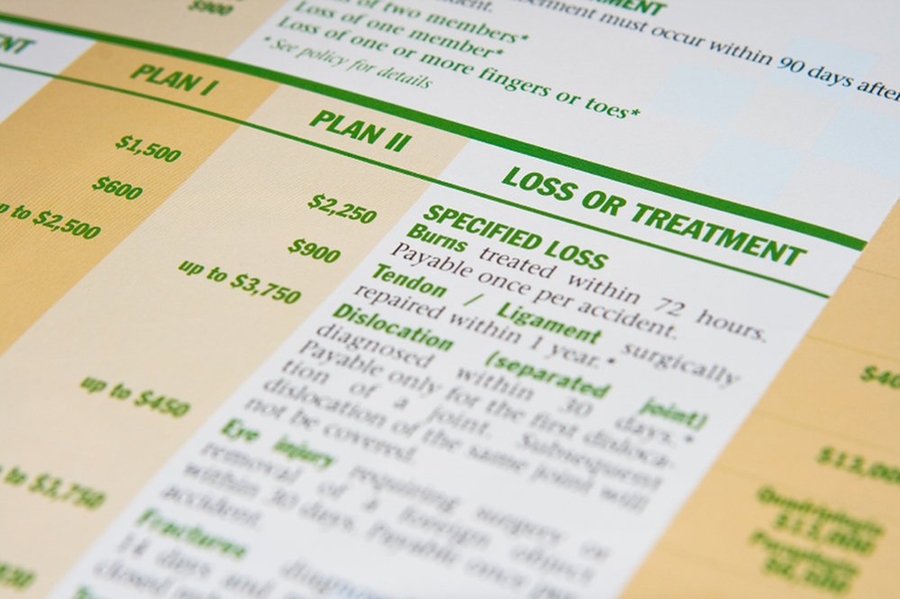

Such evidence helps explain why insurers and policymakers looking to reduce overall costs have become increasingly attracted to the concept of “consumer-directed medical care,” in which consumers pay for a larger share of medical expenses, sometimes in the form of high-deductible insurance plans. If people have to bear greater initial costs (the deductible is the amount consumers must pay before coverage kicks in), they may be less likely to seek insured medical care for seemingly marginal health issues.

But a new paper co-authored by Finkelstein suggests that forecasting the likely spending reduction associated with high deductibles requires a fine-grained approach, to account for the differing ways consumers respond to incentives in the health-care market. The research indicates that consumers select insurance plans based not only on their overall wellness level — with people in worse health opting for more robust coverage — but also on their own anticipated response to having insurance.

By scrutinizing a large data set based on choices made by employees of Alcoa, Inc., the researchers found that consumers selecting a new insurance policy who expect to reduce their use of medical care by a lot if they have to pick up additional costs shy away from high-deductible plans; by contrast, the people who opt for high-deductible plans are the ones who expect to change their health-care use the least.

Thus insurers, or at least those who expect that offering more high-deductible plans will lower their expenses, may experience smaller spending changes than they might expect if a random group of people were assigned to such plans.

“What we [find] is that if you base your forecasts on random assignment, you would substantially overestimate the spending reduction you can get by introducing high-deductible plans,” says Finkelstein, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT. “The people who select these plans aren’t randomly drawn from the population — they tend to be people who have a lower behavioral response to the [insurance] contract.”

Anticipating changes in behavior

To grasp this dynamic at work, Finkelstein suggests an analogy to an all-you-can-eat restaurant where the customers are there for two reasons: one group with consistently robust appetites, and another group who, by not having to pay a la carte, can have a larger meal than usual at a decent price. When it comes to health care, she suggests, consumers can also be divided into two similar categories: those who consistently seek a lot of coverage, and those who, given greater coverage, will change their behavior, and suddenly use much more medical care.

But how much more care do people in the second group seek? The paper, “Selection on Moral Hazard in Health Insurance,” published this month in the American Economic Review, answers that question by scrutinizing health-plan choices made between 2003 and 2006 by more than 4,000 employees at Alcoa, the global aluminum producer. The researchers were able to assess the overall health status of individuals, the health-plan choices employees made when switching coverage, and subsequent medical claims. The varying Alcoa plans offered different deductibles, but used the same network of health-care providers, meaning consumer choices were heavily based on financial concerns.

By analyzing the data this way, the researchers were able to identify the links between insurance-plan choices, overall health status, and changes in behavior — or “moral hazard” — as measured by increased claims. In quantitative terms, their bottom-line finding is that these two factors are equally significant: “Selection on moral hazard is roughly as important as selection on health risk,” the paper notes.

“There may be heterogeneity, and people may differ in how much more they spend when they get health insurance,” Finkelstein notes.

That finding could influence the way insurance firms and policymakers structure plan choices and estimate overall costs. “In a world in which people chose health plans based on not just how sick they think they are, but also on how much they think they’re going to increase their medical care use when the care is subsidized,” Finkelstein says, it could significantly affect how much health-care spending would be reduced through mechanisms such as high-deductible plans.

In addition to Finkelstein, the co-authors of the paper are Mark Cullen, a professor in Stanford University’s School of Medicine; Liran Einav, an economist at Stanford; Stephen Ryan, an economist at the University of Texas at Austin; and Paul Schrimpf, an economist at the University of British Columbia. Since 1997, Cullen has worked in coordination with Alcoa to study employee health issues.

Hard evidence — but more would be useful

Ben Handel, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley who focuses on health-care issues, calls the study “a fantastic paper,” both because of the way it reveals heterogeneity in the way people chose insurance plans and because of the granular data it contains.

“They’ve done a great job of acquiring this very, very detailed data on health-insurance choices, claims, and many aspects of these individuals,” Handel says. “I think research on these kinds of questions is moving a lot in the direction of looking for this kind of individual-level data, and [the co-authors] have been leading the charge on that.”

For her part, Finkelstein emphasizes that the topic could use additional investigation.

“I view this paper as a proof of concept that this phenomenon exists and can be important,” Finkelstein says. “Now what we need to do — both ourselves and other researchers, hopefully — is to think about this in other settings, besides just the employee benefits of Alcoa.”

The research received funding from Alcoa, Inc., as well as the National Institute on Aging, the National Science Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health, and a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

When it comes to health insurance, the existence of moral hazard is a more matter-of-fact issue: When people get health insurance, they use more medical care, as shown by research including a recent randomized study on the impact of Medicaid, which MIT economist Amy Finkelstein helped lead.

Such evidence helps explain why insurers and policymakers looking to reduce overall costs have become increasingly attracted to the concept of “consumer-directed medical care,” in which consumers pay for a larger share of medical expenses, sometimes in the form of high-deductible insurance plans. If people have to bear greater initial costs (the deductible is the amount consumers must pay before coverage kicks in), they may be less likely to seek insured medical care for seemingly marginal health issues.

But a new paper co-authored by Finkelstein suggests that forecasting the likely spending reduction associated with high deductibles requires a fine-grained approach, to account for the differing ways consumers respond to incentives in the health-care market. The research indicates that consumers select insurance plans based not only on their overall wellness level — with people in worse health opting for more robust coverage — but also on their own anticipated response to having insurance.

By scrutinizing a large data set based on choices made by employees of Alcoa, Inc., the researchers found that consumers selecting a new insurance policy who expect to reduce their use of medical care by a lot if they have to pick up additional costs shy away from high-deductible plans; by contrast, the people who opt for high-deductible plans are the ones who expect to change their health-care use the least.

Thus insurers, or at least those who expect that offering more high-deductible plans will lower their expenses, may experience smaller spending changes than they might expect if a random group of people were assigned to such plans.

“What we [find] is that if you base your forecasts on random assignment, you would substantially overestimate the spending reduction you can get by introducing high-deductible plans,” says Finkelstein, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT. “The people who select these plans aren’t randomly drawn from the population — they tend to be people who have a lower behavioral response to the [insurance] contract.”

Anticipating changes in behavior

To grasp this dynamic at work, Finkelstein suggests an analogy to an all-you-can-eat restaurant where the customers are there for two reasons: one group with consistently robust appetites, and another group who, by not having to pay a la carte, can have a larger meal than usual at a decent price. When it comes to health care, she suggests, consumers can also be divided into two similar categories: those who consistently seek a lot of coverage, and those who, given greater coverage, will change their behavior, and suddenly use much more medical care.

But how much more care do people in the second group seek? The paper, “Selection on Moral Hazard in Health Insurance,” published this month in the American Economic Review, answers that question by scrutinizing health-plan choices made between 2003 and 2006 by more than 4,000 employees at Alcoa, the global aluminum producer. The researchers were able to assess the overall health status of individuals, the health-plan choices employees made when switching coverage, and subsequent medical claims. The varying Alcoa plans offered different deductibles, but used the same network of health-care providers, meaning consumer choices were heavily based on financial concerns.

By analyzing the data this way, the researchers were able to identify the links between insurance-plan choices, overall health status, and changes in behavior — or “moral hazard” — as measured by increased claims. In quantitative terms, their bottom-line finding is that these two factors are equally significant: “Selection on moral hazard is roughly as important as selection on health risk,” the paper notes.

“There may be heterogeneity, and people may differ in how much more they spend when they get health insurance,” Finkelstein notes.

That finding could influence the way insurance firms and policymakers structure plan choices and estimate overall costs. “In a world in which people chose health plans based on not just how sick they think they are, but also on how much they think they’re going to increase their medical care use when the care is subsidized,” Finkelstein says, it could significantly affect how much health-care spending would be reduced through mechanisms such as high-deductible plans.

In addition to Finkelstein, the co-authors of the paper are Mark Cullen, a professor in Stanford University’s School of Medicine; Liran Einav, an economist at Stanford; Stephen Ryan, an economist at the University of Texas at Austin; and Paul Schrimpf, an economist at the University of British Columbia. Since 1997, Cullen has worked in coordination with Alcoa to study employee health issues.

Hard evidence — but more would be useful

Ben Handel, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley who focuses on health-care issues, calls the study “a fantastic paper,” both because of the way it reveals heterogeneity in the way people chose insurance plans and because of the granular data it contains.

“They’ve done a great job of acquiring this very, very detailed data on health-insurance choices, claims, and many aspects of these individuals,” Handel says. “I think research on these kinds of questions is moving a lot in the direction of looking for this kind of individual-level data, and [the co-authors] have been leading the charge on that.”

For her part, Finkelstein emphasizes that the topic could use additional investigation.

“I view this paper as a proof of concept that this phenomenon exists and can be important,” Finkelstein says. “Now what we need to do — both ourselves and other researchers, hopefully — is to think about this in other settings, besides just the employee benefits of Alcoa.”

The research received funding from Alcoa, Inc., as well as the National Institute on Aging, the National Science Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health, and a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration to the National Bureau of Economic Research.