The study, a randomized evaluation comparing health outcomes among more than 12,000 people in Oregon, employs the same research approach as a clinical trial, but applies it in a way that provides a window into the health outcomes of poor Americans who have been given the opportunity to get health insurance.

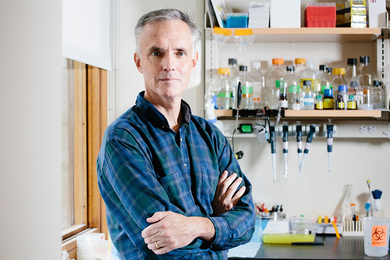

“What we found was that Medicaid significantly increased the probability of being diagnosed with diabetes, and being on diabetes medication,” says Amy Finkelstein, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT and, along with Katherine Baicker of Harvard University’s School of Public Health, the principal investigator for the study. “We find decreases in rates of depression, and we continue to find reduced financial hardship. However, we were unable to detect a decline in the incidence of diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol.”

A paper based on the study, “The Oregon Experiment — Medicaid’s Effects on Clinical Outcomes,” is being published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The findings bear on the expansion of the federal government’s Affordable Care Act (ACA), currently being phased in across the nation. The ACA provides funding for states to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults who are currently not part of the program.

Winning the lottery

The researchers analyzed the impact that Medicaid had on people over a two-year span. Among other things, they found about a 30 percent decline in the rate of depression among people on Medicaid; an increase in people being diagnosed with, and treated for, diabetes; and increases in doctor visits, use of preventative care, and prescription drugs. They also found that Medicaid reduced, by about 80 percent, the chance of a person having catastrophic out-of-pocket medical expenses, defined as spending 30 percent of one’s annual income on health care.

“That’s important, because from an economics point of view, the purpose of health insurance is to … protect you financially,” Finkelstein says.

The researchers did not find any change in three other health measures: blood pressure, cholesterol, or a blood test for diabetes. But the data does provide important indicators about the ways newly-insured people are using medical services.

“There was a big increase in the use of preventative medicine,” says Baicker, noting that Medicaid increased the use of services such as mammograms and cholesterol screening, as well as increasing doctor's office visits and prescription drugs.

Other health researchers say these findings correspond with a developing picture of how increased medical care addresses different kinds of problems over different spans of time.

“I would expect a more immediate impact when it comes to measures of mental health and emotional well-being, including depression,” says Thomas McDade, an anthropologist at Northwestern University and director of its Laboratory of Human Biology Research, who studies public-health issues. “Things like risk for cardiovascular disease, your lipid concentrations, your blood pressure, these are things that are really established over a lifetime of exposure to diet, physical activity, and psychosocial environment, so we don’t expect them to move as quickly.”

The study uses data from a unique program the state of Oregon founded in 2008, after officials realized they had Medicaid funds for about 10,000 additional uninsured residents. The state created a lottery system to fill those 10,000 slots; about 90,000 residents applied.

That lottery thus generated a group of residents gaining Medicaid coverage who were otherwise similar to the applicants still lacking coverage. Using this divide, the researchers compared to a control group of 6,387 people who signed up for the lottery and were selected to 5,842 people who applied for Medicaid but were not selected to enroll.

“We recognized the lottery as a literally once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring the rigors of a randomized controlled trial, which is the gold standard in medical and scientific research, to one of the most pressing social policy questions of our day, namely, the consequences of covering the uninsured,” Finkelstein says.

Or as Baicker puts it, “We would never accept a medical trial that didn’t have a control group.”

In particular, this kind of study, by matching two like groups of people, eliminates one longstanding problem in studying health insurance: that people in worse health may seek out health insurance more often than those in good health do, thus making it appear, at a glance, that having health insurance does not help improve medical outcomes.

“The whole tension with studying the effects of insurance is, you have to wonder why some people have insurance and other people don’t, and whether those reasons could be related to the outcomes you’re studying,” Finkelstein explains, “like the possibility that people who are sicker seek out insurance more. So you can get perverse results [on the surface], indicating that health insurance makes you sicker, not because it actually does, but because of the kinds of people who are seeking it out.”

As McDade also notes, “It’s a true experiment, and these kinds of opportunities do not come along very often.”

Growing body of evidence

Medicaid is the program, administered jointly by the federal government and the states, that provides health insurance for (mostly) low-income U.S. citizens; it is not to be confused with Medicare, the federal health insurance program for senior citizens, although both were initiated in 1965. Eligibility for Medicaid varies slightly from state to state; in Oregon, adults below the federal poverty guidelines established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (in 2013, an annual income of $11,490 per person, and $23,550 for a family of four) while meeting other requirements were eligible to apply for the insurance lottery.

In 2011, researchers released results from an initial related study, which found that after about one year of coverage, the lottery enrollees in Oregon’s Medicaid program did, in fact, use more medical care, suffer from less financial strain, and report themselves to be in better health. The current study augments that one by analyzing a longer time period and adding clinical health data to the self-reported information.

Finkelstein says she hopes the current study will gain public attention and consideration by policymakers.

“Maybe I’m overly optimistic, but I believe that rigorous scientific evidence finds an important voice in our policy discussions,” Finkelstein says.

In addition to Baicker and Finkelstein, co-authors of the paper are Heidi Allen of Columbia University; Mira Bernstein of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); Jonathan Gruber, an MIT economist specializing in health-care issues; Joseph P. Newhouse, a health-care economist at Harvard who helped pioneer the idea of randomized trials about health insurance; Eric C. Schneider of RAND; Sarah L. Taubman of the NBER; Bill J. Wright of the Providence Center for Outcomes Research on Education; and Alan Zaslavsky of Harvard.

The research was also conducted with the Oregon Health Study Group, which includes Matt Carlson of Portland State University, Tina Edlund of the Oregon Health Authority, Charles Gallia of the Oregon Department of Human Services, and Jeanene Smith of the Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research.

The project received funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the California HealthCare Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, the U.S. Social Security Administration, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.