These days, senior Bethany Tomerlin is just like any other MIT student: She juggles a host of academic and research commitments, plays flute in the MIT Marching Band, and — when she finds a sliver of spare time — indulges what she calls her “pop culture vice” with friends in her dormitory.

But Tomerlin, a materials science and engineering major who grew up in southern California, has overcome intense physical challenges that make her hard-won accomplishments stand out even among those of her peers. She was born with mild cerebral palsy and sensory integration disorder, wore leg braces until sixth grade and had a childhood punctuated by hospital visits and physical therapy several times a week. (Cerebral palsy refers to a spectrum of disorders involving brain and nervous-system functions, often affecting motor abilities.) Tomerlin recalls her frustration in elementary school, when — despite her enthusiasm for schoolwork — she had difficulty learning to pick up and maneuver a pencil.

“My mom says in the fifth grade I determined that I was going to be smartest person anyone met, so when they looked at me they’d only see how smart I was and not my disability,” Tomerlin says.

Now, Tomerlin says, her motor issues are largely under control, although they still “pop up unexpectedly.”

“I don’t have a driver’s license,” she says. “It was hard to have something that seemed so easy for my peers be so hard for me.”

But she gives much credit to her doctors and therapists, whose “amazing” efforts and early intervention approach allowed her to lead as normal a life as possible.

“It definitely made me want to choose a field where I can give back, and help the world in some way,” she says.

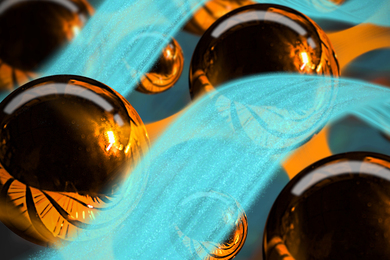

When she first arrived at MIT, Tomerlin thought that field might be energy. Last summer, she did research at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology through the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives, or MISTI, working on efforts to improve the efficiency of solar thermal cells. Solar thermal cells work by absorbing the sun’s heat to heat a liquid, which is then used to turn turbines and generate power — so, the hotter temperatures the cells can withstand, the more of the sun’s heat they can convert into energy. Tomerlin’s project involved developing and testing a cobalt coating for such cells to increase their heat thresholds.

Doing research in another country was a growing experience both intellectually and culturally for Tomerlin.

“You come away with both a sense of how universal science and engineering is, as well as how each country puts its own spin on it,” she says.

But while Tomerlin says she’s attracted to the global-scale problems of energy, over the course of her time at the Institute she learned that she ultimately prefers materials science — especially the study of biomaterials, which could help develop new cures and therapies for people with diseases similar to her own.

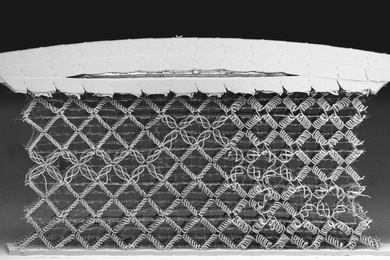

Next semester, she’ll be completing a thesis project in the lab of Linn Hobbs, a professor of materials science and nuclear science and engineering, analyzing the interface between bones and tendons. Her plan is to study how the cells in this juncture, and the connections between them, change over time after an injury.

“Understanding the interface [between bone and tendon] and what happens there will give a better indication of diagnostic stuff — whether it’s healed or it’s not healed — and let us speculate on ways to speed up the recovery,” Tomerlin explains.

After graduating in June, Tomerlin hopes to go abroad once more, this time to Brazil — to get started on her career, improve her Portuguese and experience what she calls “such a happening place right now.” She’s exploring options for materials science internships in various Brazilian cities through MISTI.

Eventually, she says, her dream job is to work for a company such as Disney, where she can combine her artistic sense and engineering know-how to produce brand-new products and spectacles.

“I’m an engineer, I like to create things,” she says. “At Disney, you can create whole worlds.”

But Tomerlin, a materials science and engineering major who grew up in southern California, has overcome intense physical challenges that make her hard-won accomplishments stand out even among those of her peers. She was born with mild cerebral palsy and sensory integration disorder, wore leg braces until sixth grade and had a childhood punctuated by hospital visits and physical therapy several times a week. (Cerebral palsy refers to a spectrum of disorders involving brain and nervous-system functions, often affecting motor abilities.) Tomerlin recalls her frustration in elementary school, when — despite her enthusiasm for schoolwork — she had difficulty learning to pick up and maneuver a pencil.

“My mom says in the fifth grade I determined that I was going to be smartest person anyone met, so when they looked at me they’d only see how smart I was and not my disability,” Tomerlin says.

Now, Tomerlin says, her motor issues are largely under control, although they still “pop up unexpectedly.”

“I don’t have a driver’s license,” she says. “It was hard to have something that seemed so easy for my peers be so hard for me.”

But she gives much credit to her doctors and therapists, whose “amazing” efforts and early intervention approach allowed her to lead as normal a life as possible.

“It definitely made me want to choose a field where I can give back, and help the world in some way,” she says.

When she first arrived at MIT, Tomerlin thought that field might be energy. Last summer, she did research at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology through the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives, or MISTI, working on efforts to improve the efficiency of solar thermal cells. Solar thermal cells work by absorbing the sun’s heat to heat a liquid, which is then used to turn turbines and generate power — so, the hotter temperatures the cells can withstand, the more of the sun’s heat they can convert into energy. Tomerlin’s project involved developing and testing a cobalt coating for such cells to increase their heat thresholds.

Doing research in another country was a growing experience both intellectually and culturally for Tomerlin.

“You come away with both a sense of how universal science and engineering is, as well as how each country puts its own spin on it,” she says.

But while Tomerlin says she’s attracted to the global-scale problems of energy, over the course of her time at the Institute she learned that she ultimately prefers materials science — especially the study of biomaterials, which could help develop new cures and therapies for people with diseases similar to her own.

Next semester, she’ll be completing a thesis project in the lab of Linn Hobbs, a professor of materials science and nuclear science and engineering, analyzing the interface between bones and tendons. Her plan is to study how the cells in this juncture, and the connections between them, change over time after an injury.

“Understanding the interface [between bone and tendon] and what happens there will give a better indication of diagnostic stuff — whether it’s healed or it’s not healed — and let us speculate on ways to speed up the recovery,” Tomerlin explains.

After graduating in June, Tomerlin hopes to go abroad once more, this time to Brazil — to get started on her career, improve her Portuguese and experience what she calls “such a happening place right now.” She’s exploring options for materials science internships in various Brazilian cities through MISTI.

Eventually, she says, her dream job is to work for a company such as Disney, where she can combine her artistic sense and engineering know-how to produce brand-new products and spectacles.

“I’m an engineer, I like to create things,” she says. “At Disney, you can create whole worlds.”