‘150 years of MIT’ is a series that looks at specific people and moments from MIT’s 150-year history and explains their lasting effect on the Institute, the nation and the world. See the full interactive timeline at the MIT150 site.

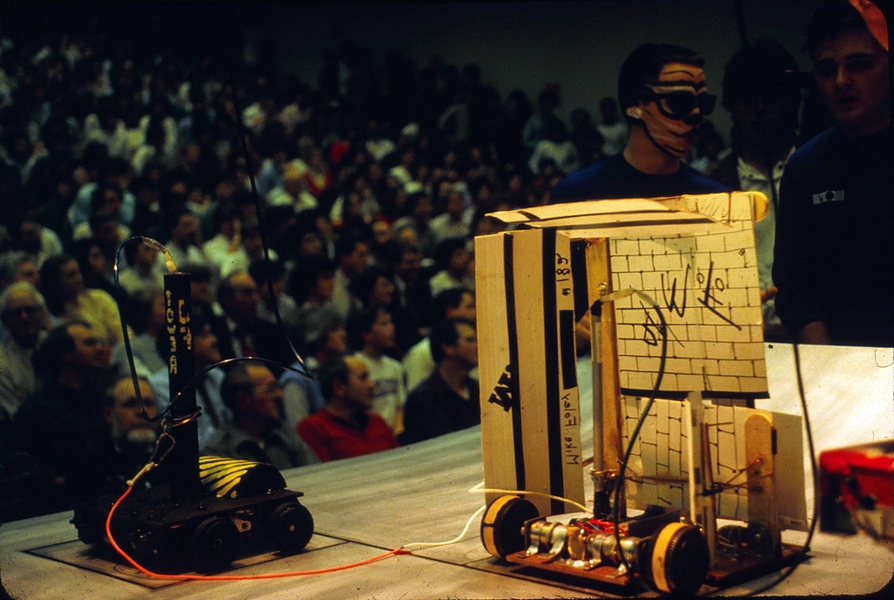

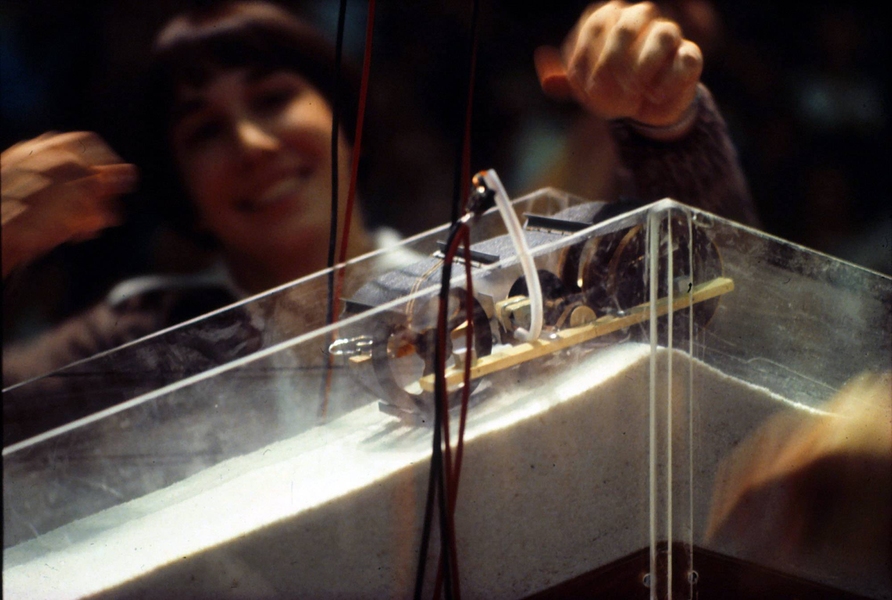

If you walk in to MIT’s Johnson Athletic Center on a certain evening at the end of the spring semester, the sounds coming from the throng inside — bursts of clapping, footstomping and cheering — would lead you to assume that you’re approaching an athletic event. And in a sense, the finale of the class called 2.007, “Introduction to Design and Manufacturing,” is indeed a kind of athletic competition, except that the participants out on the playing field are all robots, designed and built in one semester by teams of students, and they are carrying out tasks such as collecting balls or blocks in one place and carrying them to a particular chute or box or making a neat stack. Points are awarded for these tasks, and a winner is honored at the end of the single-elimination match.

But what’s being enthusiastically celebrated by the crowd is not athletic prowess but learning in action. The competition, now four decades old, is an Olympics of engineering.

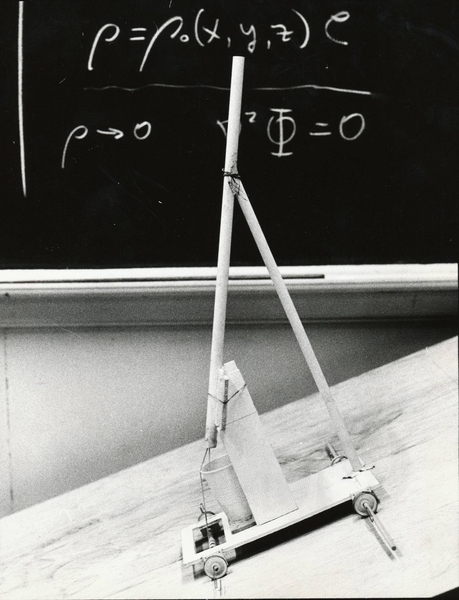

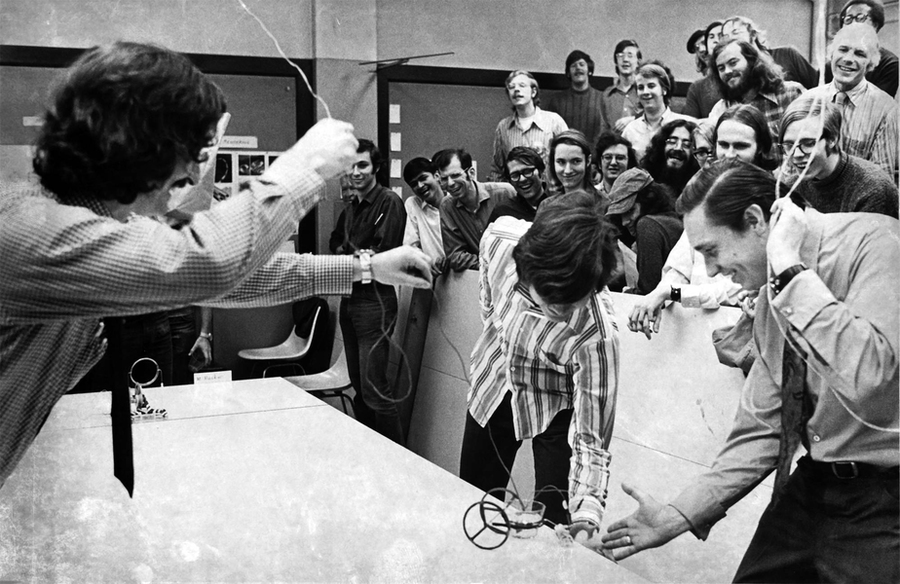

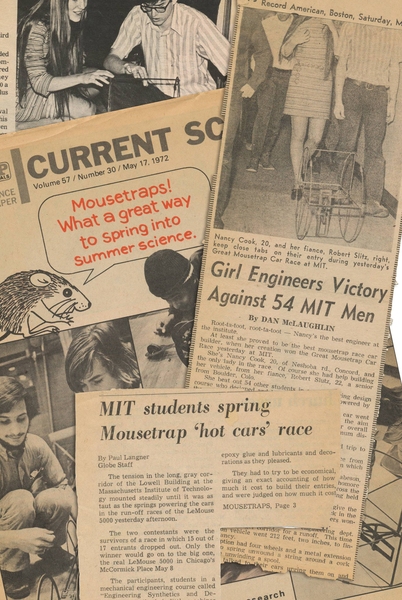

The contest has grown steadily since its humble beginnings in 1970, and in that time has spawned a host of imitators at MIT, at other colleges, and in schools around the world. But that first year, when the course was still called 2.70, there were no robots at all: The competition was to build a mechanical device, out of a set of relatively simple wooden and metal parts, that would roll down a ramp at a precisely controlled rate.

Woodie Flowers SM '68, MEng '71, PhD '73, now the Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Emeritus, was a graduate student and teaching assistant in the course that year, he recalls. The class had long required students to design and build a project of some kind, but Flowers recalls how some students spent more time on the decision process than on the fabrication, and thus faced a “frantic struggle at the end” to finish the project.

So, instead of leaving it as an open-ended project, Flowers decided to give each team of students an identical kit of parts, from which they all had to build a device to accomplish the same specific task. In the first year, the task was to make something that could move down a ramp in exactly three minutes. “That worked much better,” Flowers says, “because students didn’t flounder around so long figuring out what to do.”

The other key innovation, framing the course as building up to a competition in which all the students’ projects would be tested against each other, helped to focus their minds on meeting deadlines — and tapped into MIT students’ natural competitiveness in order to provide extra motivation. However, Flowers stresses, “competition is not as important as having a meaningful experience and helping others in the process” — an attitude he describes as “gracious professionalism.” While winners are announced at the end of the competition, students’ finishing place is not reflected in the grades for the class.

Although the winner can be pretty sure of getting an A, so might a student who produces an ingenious and unique design that doesn’t even make it past the first elimination round. Some students “would build things that had no chance of winning, but if they did something interesting, it was celebrated,” Flowers says.

One of the early competitions was filmed for an episode of a PBS series called Discover: The world of science, and proved to be the most popular segment of that series. Soon after, the producers hired Flowers to host a successor to the program, Scientific American Frontiers, partly based on the popularity of the program on the MIT competition.

From mechanics to robotics

Over the years, the kits of parts the students got to work with, and the playing fields and the tasks to be performed, have become more complex and sophisticated. While the first few contests involved purely mechanical devices, over time they have become more electronic and robotic. In 1992, Flowers teamed up with inventor Dean Kamen, creator of the Segway transporter, to launch a robotic competition based on the principles developed in the MIT class.

That competition, dubbed FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), was for teams of high school students, who were paired with mentors who were professional engineers. That contest has grown with every passing year, from 28 teams in the first year to 150,000 students involved last year, and winners are sometimes invited to the White House. Last fall, NASA provided a $20 million grant to the contest. It has also grown to include elementary-school competitions, and has attracted teams from around the world.

Woodie Flowers discusses course 2.70 and how it evolved into MIT’s annual 2.007 mechanical engineering contest.

Video: AMPS MIT Video Productions (watch the full documentary)

Over the years, the tasks posed and the materials provided in the MIT class have changed, but its basic structure and its hands-on emphasis has not. Mechanical engineering professor David Wallace, who taught sections in the class during the 1990s, recalls that many students in the class had never really had a chance to create something from scratch before, and they “felt very empowered by doing so” in the class. That kind of transformation is one reason the concept “has had a wide-ranging impact on the curriculum at many schools,” he says. Similar classes have been set up at Caltech, Georgia Tech, Tulane and several others places.

One of the big challenges for those who have taught the class over the years has been coming up with suitable challenges each year — not so hard that they are unachievable, not so easy that they’re trivial, and, perhaps most importantly, open-ended enough “so it has a lot of different potential design approaches,” Wallace says. Often the themes are based on currently popular movies or ideas — one year it was based on the movie Wall-E, for example, with the robots attempting to collect and recycle garbage; another contest was based on the MIT mascot, the beaver, with robots attempting to gather “logs” and arrange them to dam up a “river.”

The concept has also spawned a host of imitators within MIT. Many other courses and Independent Activities Period contests, such as the IAP LEGO robot competition 6.270, a website design contest and an underwater vehicle competition use the same basic format, providing teams of students with a set task, a limited time to achieve it, and a big competitive finale. Other contests feature such things as the design of toys or consumer products, competitive videogaming with robotic players, and the design of poker-playing computer programs.

But at its essence, the class is just a direct outgrowth of the original vision of William Barton Rogers when he founded MIT in 1861, explains Alexander Slocum ’82, SM ’83, PhD ’85, the Neil and Jane Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering, who taught 2.007 for 14 years, starting in 1994. It’s an embodiment of “the words he used to found MIT: mind and hand, mens et manus,” he says. “It’s a coupling between science and engineering.”

Introducing new elements

Each teacher who has taken on the class has added new elements. One of Slocum’s innovations was to include student teachers to work with each of the student teams, as well as adding a requirement for “project scheduling” and a system of documenting the reasoning behind every decision made in the design process — a reflection of the way real industrial-engineering design is structured, so that graduates will come away with “a clear methodology for how to apply the process in an industrial environment,” he says.

But Slocum stresses that the class has become something much larger than any of its instructors. “No one owns, 2.007, 2.007 owns you,” he says. “You’re just the current caretaker.”

The latest caretaker, now starting his third year of teaching the class, is Daniel Frey PhD ’97, associate professor of mechanical engineering and engineering systems. One of his innovations was to give students the option of working on a different design challenge, without the competitive element. But he was surprised to find that most of the students really do prefer to compete.

Additionally, Frey is working with co-instructor David Gossard, a professor of mechanical engineering, on a video that shows a sample design and construction process from start to finish, to help students who have never built things before to visualize how the process works.

Flowers, who now spends much of his time working on the still-growing FIRST competition, remains a strong believer in the whole approach embodied in that 2.007 class and its host of followers: the idea of learning by actually making things, fine-tuning them, and getting them to work — and doing so in an atmosphere of fun, friendly competition. “Doing things really does augment your understanding of what you do,” he says.

If you walk in to MIT’s Johnson Athletic Center on a certain evening at the end of the spring semester, the sounds coming from the throng inside — bursts of clapping, footstomping and cheering — would lead you to assume that you’re approaching an athletic event. And in a sense, the finale of the class called 2.007, “Introduction to Design and Manufacturing,” is indeed a kind of athletic competition, except that the participants out on the playing field are all robots, designed and built in one semester by teams of students, and they are carrying out tasks such as collecting balls or blocks in one place and carrying them to a particular chute or box or making a neat stack. Points are awarded for these tasks, and a winner is honored at the end of the single-elimination match.

But what’s being enthusiastically celebrated by the crowd is not athletic prowess but learning in action. The competition, now four decades old, is an Olympics of engineering.

The contest has grown steadily since its humble beginnings in 1970, and in that time has spawned a host of imitators at MIT, at other colleges, and in schools around the world. But that first year, when the course was still called 2.70, there were no robots at all: The competition was to build a mechanical device, out of a set of relatively simple wooden and metal parts, that would roll down a ramp at a precisely controlled rate.

Woodie Flowers SM '68, MEng '71, PhD '73, now the Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Emeritus, was a graduate student and teaching assistant in the course that year, he recalls. The class had long required students to design and build a project of some kind, but Flowers recalls how some students spent more time on the decision process than on the fabrication, and thus faced a “frantic struggle at the end” to finish the project.

So, instead of leaving it as an open-ended project, Flowers decided to give each team of students an identical kit of parts, from which they all had to build a device to accomplish the same specific task. In the first year, the task was to make something that could move down a ramp in exactly three minutes. “That worked much better,” Flowers says, “because students didn’t flounder around so long figuring out what to do.”

The other key innovation, framing the course as building up to a competition in which all the students’ projects would be tested against each other, helped to focus their minds on meeting deadlines — and tapped into MIT students’ natural competitiveness in order to provide extra motivation. However, Flowers stresses, “competition is not as important as having a meaningful experience and helping others in the process” — an attitude he describes as “gracious professionalism.” While winners are announced at the end of the competition, students’ finishing place is not reflected in the grades for the class.

Although the winner can be pretty sure of getting an A, so might a student who produces an ingenious and unique design that doesn’t even make it past the first elimination round. Some students “would build things that had no chance of winning, but if they did something interesting, it was celebrated,” Flowers says.

One of the early competitions was filmed for an episode of a PBS series called Discover: The world of science, and proved to be the most popular segment of that series. Soon after, the producers hired Flowers to host a successor to the program, Scientific American Frontiers, partly based on the popularity of the program on the MIT competition.

From mechanics to robotics

Over the years, the kits of parts the students got to work with, and the playing fields and the tasks to be performed, have become more complex and sophisticated. While the first few contests involved purely mechanical devices, over time they have become more electronic and robotic. In 1992, Flowers teamed up with inventor Dean Kamen, creator of the Segway transporter, to launch a robotic competition based on the principles developed in the MIT class.

That competition, dubbed FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), was for teams of high school students, who were paired with mentors who were professional engineers. That contest has grown with every passing year, from 28 teams in the first year to 150,000 students involved last year, and winners are sometimes invited to the White House. Last fall, NASA provided a $20 million grant to the contest. It has also grown to include elementary-school competitions, and has attracted teams from around the world.

Woodie Flowers discusses course 2.70 and how it evolved into MIT’s annual 2.007 mechanical engineering contest.

Video: AMPS MIT Video Productions (watch the full documentary)

Over the years, the tasks posed and the materials provided in the MIT class have changed, but its basic structure and its hands-on emphasis has not. Mechanical engineering professor David Wallace, who taught sections in the class during the 1990s, recalls that many students in the class had never really had a chance to create something from scratch before, and they “felt very empowered by doing so” in the class. That kind of transformation is one reason the concept “has had a wide-ranging impact on the curriculum at many schools,” he says. Similar classes have been set up at Caltech, Georgia Tech, Tulane and several others places.

One of the big challenges for those who have taught the class over the years has been coming up with suitable challenges each year — not so hard that they are unachievable, not so easy that they’re trivial, and, perhaps most importantly, open-ended enough “so it has a lot of different potential design approaches,” Wallace says. Often the themes are based on currently popular movies or ideas — one year it was based on the movie Wall-E, for example, with the robots attempting to collect and recycle garbage; another contest was based on the MIT mascot, the beaver, with robots attempting to gather “logs” and arrange them to dam up a “river.”

The concept has also spawned a host of imitators within MIT. Many other courses and Independent Activities Period contests, such as the IAP LEGO robot competition 6.270, a website design contest and an underwater vehicle competition use the same basic format, providing teams of students with a set task, a limited time to achieve it, and a big competitive finale. Other contests feature such things as the design of toys or consumer products, competitive videogaming with robotic players, and the design of poker-playing computer programs.

But at its essence, the class is just a direct outgrowth of the original vision of William Barton Rogers when he founded MIT in 1861, explains Alexander Slocum ’82, SM ’83, PhD ’85, the Neil and Jane Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering, who taught 2.007 for 14 years, starting in 1994. It’s an embodiment of “the words he used to found MIT: mind and hand, mens et manus,” he says. “It’s a coupling between science and engineering.”

Introducing new elements

Each teacher who has taken on the class has added new elements. One of Slocum’s innovations was to include student teachers to work with each of the student teams, as well as adding a requirement for “project scheduling” and a system of documenting the reasoning behind every decision made in the design process — a reflection of the way real industrial-engineering design is structured, so that graduates will come away with “a clear methodology for how to apply the process in an industrial environment,” he says.

But Slocum stresses that the class has become something much larger than any of its instructors. “No one owns, 2.007, 2.007 owns you,” he says. “You’re just the current caretaker.”

The latest caretaker, now starting his third year of teaching the class, is Daniel Frey PhD ’97, associate professor of mechanical engineering and engineering systems. One of his innovations was to give students the option of working on a different design challenge, without the competitive element. But he was surprised to find that most of the students really do prefer to compete.

Additionally, Frey is working with co-instructor David Gossard, a professor of mechanical engineering, on a video that shows a sample design and construction process from start to finish, to help students who have never built things before to visualize how the process works.

Flowers, who now spends much of his time working on the still-growing FIRST competition, remains a strong believer in the whole approach embodied in that 2.007 class and its host of followers: the idea of learning by actually making things, fine-tuning them, and getting them to work — and doing so in an atmosphere of fun, friendly competition. “Doing things really does augment your understanding of what you do,” he says.