Charles Julius Batterman, a former national diving champion and longtime MIT diving coach who was among the first to take a scientific approach to the sport, died March 31 in Peterborough, N.H. He was 87.

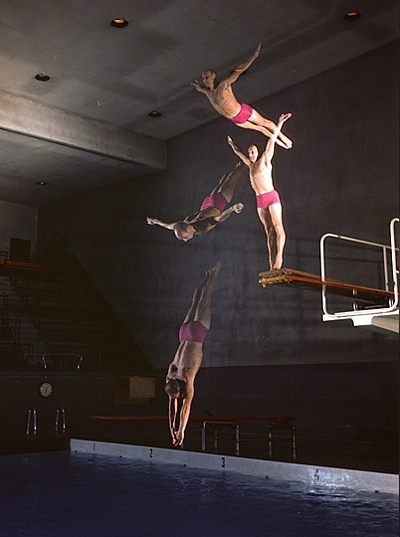

Batterman was the subject of some of Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton’s strikingly beautiful stroboscopic photographs, which captured the diver at various points as he twirled through the air on his way to the water. But Batterman was best known professionally for authoring The Techniques of Springboard Diving (MIT Press, 1968), the first book to apply physics principles to the analysis of dives. The book is illustrated both with Edgerton’s photographs and with Batterman’s own pen-and-ink drawings.

“From the standpoint of mechanical analysis and the scientific approach, the book has no equal,” said Bob Webster, winner of gold medals at the 1960 and 1964 Olympics. Diver Bob Clotworthy wrote in the foreword to the book, “In 1956, I had the opportunity to be coached by Charlie Batterman. I was already a National Champion, and an Olympian, but in a few weekends I found out how little I really knew about diving. Charlie was the first one to stress the importance of the scientific approach.”

Batterman was born June 10, 1922, in Brooklyn, N.Y., to parents who had emigrated as children from Eastern Europe. He attended Ohio State University, where he was a member of the school’s national-championship swimming teams in 1942 and 1943.

He and his future wife, Ruth Lester Fink, met as teenage counselors at summer camp; they married in 1944. That same year, while he was earning his MA part-time at Columbia University, Batterman was National Inter-Collegiate and National AAU diving champion in both the high board and the low board. He was named to the honorary 1944 Olympic team (there were no Olympic games that year because of the war).

Batterman, his wife and his infant daughter spent the summer at New York’s Jones Beach, where Batterman performed in diving shows in order to support his family. That and several jobs coaching high-school basketball disqualified him from competing in the 1948 Olympic games, on the grounds that he was a professional.

In 1949, Batterman went to Harvard University as an assistant coach. In 1956 he was appointed assistant professor of physical education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he also coached swimming, diving, soccer, lacrosse and water polo.

In 1968, he wrote a children’s book, How to Star in Swimming and Diving. It was widely distributed through Scholastic Book Services and reprinted several times by Four Winds Press.

In the summers of 1967 and 1968, under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State, Batterman traveled to Poland to set up training camps to prepare young Polish swimmers and divers for international competition. During his stay, the swimmers he coached broke between 15 and 20 Polish national records.

Batterman officially retired from MIT in 1987. His New England colleagues in the diving and swimming community honored him by creating the Charles Batterman Men’s and Women’s Diving Coach of the Year awards and the annual Charlie Batterman Relays.

In addition to being a teacher and an athlete, Batterman was an accomplished amateur artist and enjoyed painting watercolors. Among Batterman’s friends was American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, his roommate at Ohio State; in 1942, Lichtenstein created an oil painting of Batterman’s feet soaking in a basin.

“Charlie loved music, sang and danced and was the life of any party he attended. He was a true ‘lebenskunstler’ — an artist of life,” said longtime friend Ethan Bolker, noting that Batterman designed his icosahedral house in Hancock, N.H., where he and Ruth lived after Batterman retired.

His wife suffered a stroke, and for years afterward, Batterman cared for her himself in their Hancock house, despite the well-meant advice of friends and family who were sure the two of them could manage only in a retirement home. They were married for 60 years before her death in 2004.

Batterman was also preceded in death by a daughter, Amy Beissel. He is survived by his son, Henry Batterman of Florence, Italy; his daughter, Nora Campbell, of Cambridge, Mass.; five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Batterman was the subject of some of Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton’s strikingly beautiful stroboscopic photographs, which captured the diver at various points as he twirled through the air on his way to the water. But Batterman was best known professionally for authoring The Techniques of Springboard Diving (MIT Press, 1968), the first book to apply physics principles to the analysis of dives. The book is illustrated both with Edgerton’s photographs and with Batterman’s own pen-and-ink drawings.

“From the standpoint of mechanical analysis and the scientific approach, the book has no equal,” said Bob Webster, winner of gold medals at the 1960 and 1964 Olympics. Diver Bob Clotworthy wrote in the foreword to the book, “In 1956, I had the opportunity to be coached by Charlie Batterman. I was already a National Champion, and an Olympian, but in a few weekends I found out how little I really knew about diving. Charlie was the first one to stress the importance of the scientific approach.”

Batterman was born June 10, 1922, in Brooklyn, N.Y., to parents who had emigrated as children from Eastern Europe. He attended Ohio State University, where he was a member of the school’s national-championship swimming teams in 1942 and 1943.

He and his future wife, Ruth Lester Fink, met as teenage counselors at summer camp; they married in 1944. That same year, while he was earning his MA part-time at Columbia University, Batterman was National Inter-Collegiate and National AAU diving champion in both the high board and the low board. He was named to the honorary 1944 Olympic team (there were no Olympic games that year because of the war).

Batterman, his wife and his infant daughter spent the summer at New York’s Jones Beach, where Batterman performed in diving shows in order to support his family. That and several jobs coaching high-school basketball disqualified him from competing in the 1948 Olympic games, on the grounds that he was a professional.

In 1949, Batterman went to Harvard University as an assistant coach. In 1956 he was appointed assistant professor of physical education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he also coached swimming, diving, soccer, lacrosse and water polo.

In 1968, he wrote a children’s book, How to Star in Swimming and Diving. It was widely distributed through Scholastic Book Services and reprinted several times by Four Winds Press.

In the summers of 1967 and 1968, under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State, Batterman traveled to Poland to set up training camps to prepare young Polish swimmers and divers for international competition. During his stay, the swimmers he coached broke between 15 and 20 Polish national records.

Batterman officially retired from MIT in 1987. His New England colleagues in the diving and swimming community honored him by creating the Charles Batterman Men’s and Women’s Diving Coach of the Year awards and the annual Charlie Batterman Relays.

In addition to being a teacher and an athlete, Batterman was an accomplished amateur artist and enjoyed painting watercolors. Among Batterman’s friends was American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, his roommate at Ohio State; in 1942, Lichtenstein created an oil painting of Batterman’s feet soaking in a basin.

“Charlie loved music, sang and danced and was the life of any party he attended. He was a true ‘lebenskunstler’ — an artist of life,” said longtime friend Ethan Bolker, noting that Batterman designed his icosahedral house in Hancock, N.H., where he and Ruth lived after Batterman retired.

His wife suffered a stroke, and for years afterward, Batterman cared for her himself in their Hancock house, despite the well-meant advice of friends and family who were sure the two of them could manage only in a retirement home. They were married for 60 years before her death in 2004.

Batterman was also preceded in death by a daughter, Amy Beissel. He is survived by his son, Henry Batterman of Florence, Italy; his daughter, Nora Campbell, of Cambridge, Mass.; five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.