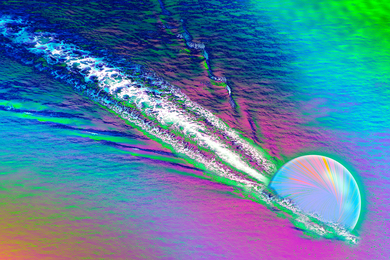

New research by MIT scientists suggests that carbon nanotubes — tube-shaped molecules of pure carbon — could be formed into tiny springs capable of storing as much energy, pound for pound, as state-of-the-art lithium-ion batteries, and potentially more durably and reliably.

Imagine, for example, an emergency backup power supply or alarm system that can be left in place for many years without losing its "charge," portable mechanical tools like leaf blowers that work without the noise and fumes of small gasoline engines, or devices to be sent down oil wells or into other harsh environments where the performance of ordinary batteries would be degraded by temperature extremes. That's the kind of potential that carbon nanotube springs could hold, according to Carol Livermore, associate professor of mechanical engineering. Carbon nanotube springs, she found, can potentially store more than a thousand times more energy for their weight than steel springs.

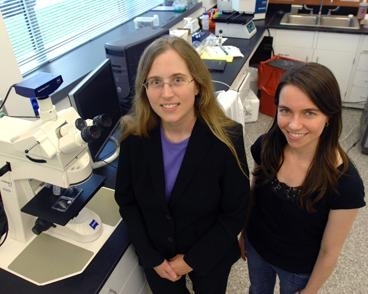

Two papers describing Livermore and her team's findings on energy storage in carbon nanotube springs have just been published. A paper describing a theoretical analysis of the springs' potential, co-authored by Livermore, graduate student Frances Hill and Timothy Havel SM ’07, appeared in June in the journal Nanotechnology. Another paper, by Livermore, Hill, Havel and A. John Hart SM ’02, PhD ’06, now a professor at the University of Michigan, describing laboratory tests that demonstrate that nanotubes really can exceed the energy storage potential of steel, appears in the September issue of the Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering.

Theoretical analysis shows the carbon nanotube springs could ultimately have an energy density — a measure of the amount of energy that can be stored in a given weight of material — more than 1,000 times that of steel springs, and comparable to that of the best lithium-ion batteries.

With a snap or a tick-tock

For some applications, springs can have advantages over other ways of storing energy, Livermore explains. Unlike batteries, for example, springs can deliver the stored energy effectively either in a rapid, intense burst, or slowly and steadily over a long period — as exemplified by the difference between the spring in a mousetrap or in a windup clock. Also, unlike batteries, stored energy in springs normally doesn't slowly leak away over time; a mousetrap can remain poised to snap for years without dissipating any of its energy.

For that reason, such systems might lend themselves to applications for emergency backup systems. With batteries, such devices need to be tested frequently to make sure they still have full power, and replace or recharge the batteries when they run down, but with a spring-based system, in principle "you could stick it on the wall and forget it," Livermore says.

Livermore says that the springs made from these minuscule tubes might find their first uses in large devices rather than in micro-electromechanical devices. For one thing, the best uses of such springs may be in cases where the energy is stored mechanically and then used to drive a mechanical load, rather than converting it to electricity first.

Any system that requires conversion from mechanical energy to electrical and back again, using a generator and then a motor, will lose some of its energy in the process through friction and other processes that produce waste heat. For example, a regenerative braking system that stores energy as a bicycle coasts downhill and then releases that energy to boost power while going uphill might be more efficient if it stores and releases its energy from a spring instead of an electrical system, she says. In addition to the direct energy losses, about half the weight of such electromechanical systems currently is in the motor-generator used for the conversion — something that wouldn't be needed in a purely mechanical system.

One reason the microscopic tubes lend themselves to being made into longer fibers that can make effective springs is that the nanotube molecules themselves have a strong tendency to stick to each other. That makes it relatively easy to spin them into long fibers — much as strands of wool can be spun into yarn — and this is something many researchers around the world are working on. "In fact," Livermore says, the fibers are so sticky that "we had some comical moments when you're trying to get them off your tweezers." But that quality means that ultimately it may be possible to "make something that looks like a carbon nanotube and is as long as you want it to be."

Tough and long-lasting

Carbon nanotube springs also have the advantage that they are relatively unaffected by differences in temperature and other environmental factors, whereas batteries need to be optimized for a particular set of conditions, usually to operate at normal room temperature. Nanotube springs might thus find applications in extreme conditions, such as for devices to be used in an oil borehole subjected to high temperature and pressure, or on space vehicles where temperature can fluctuate between extreme heat and extreme cold.

"They should also be able to charge and recharge many times without a loss of performance," Livermore says, although the actual performance over time still needs to be tested.

Livermore says that to create devices that come close to achieving the theoretically possible high energy density of the material will require plenty of additional basic research, followed by engineering work. Among other things, the initial lab tests used fibers of carbon nanotubes joined in parallel, but creating a practical energy storage device will require assembling nanotubes into longer and likely thicker fibers without losing their key advantages.

"These scaled-up springs need to be large (i.e., incorporating many carbon nanotubes), but those individual carbon nanotubes need to work well enough together in the overall assembly of tubes for it to have comparable properties to the individual tubes," Livermore says. "This is not easy to do."

Rod Ruoff, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Texas, adds that while the theoretical energy density of such systems is high, present ways of making carbon nanotubes are limited in their ability to produce highly concentrated bundles, and so "It appears to me that the 'low hanging fruit' here is to find important applications where the energy density on per weight basis outweighs the energy density on a per volume basis." But, he adds, if Livermore and her team are able to produce denser bundles of carbon nanotubes, "then there are exciting possibilities for mechanical energy storage" with such systems.

The group has already filed for a patent on the technology. Their work has been funded by the Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation Ignition grant and by an MIT Energy Initiative seed grant.

Imagine, for example, an emergency backup power supply or alarm system that can be left in place for many years without losing its "charge," portable mechanical tools like leaf blowers that work without the noise and fumes of small gasoline engines, or devices to be sent down oil wells or into other harsh environments where the performance of ordinary batteries would be degraded by temperature extremes. That's the kind of potential that carbon nanotube springs could hold, according to Carol Livermore, associate professor of mechanical engineering. Carbon nanotube springs, she found, can potentially store more than a thousand times more energy for their weight than steel springs.

Two papers describing Livermore and her team's findings on energy storage in carbon nanotube springs have just been published. A paper describing a theoretical analysis of the springs' potential, co-authored by Livermore, graduate student Frances Hill and Timothy Havel SM ’07, appeared in June in the journal Nanotechnology. Another paper, by Livermore, Hill, Havel and A. John Hart SM ’02, PhD ’06, now a professor at the University of Michigan, describing laboratory tests that demonstrate that nanotubes really can exceed the energy storage potential of steel, appears in the September issue of the Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering.

Theoretical analysis shows the carbon nanotube springs could ultimately have an energy density — a measure of the amount of energy that can be stored in a given weight of material — more than 1,000 times that of steel springs, and comparable to that of the best lithium-ion batteries.

With a snap or a tick-tock

For some applications, springs can have advantages over other ways of storing energy, Livermore explains. Unlike batteries, for example, springs can deliver the stored energy effectively either in a rapid, intense burst, or slowly and steadily over a long period — as exemplified by the difference between the spring in a mousetrap or in a windup clock. Also, unlike batteries, stored energy in springs normally doesn't slowly leak away over time; a mousetrap can remain poised to snap for years without dissipating any of its energy.

For that reason, such systems might lend themselves to applications for emergency backup systems. With batteries, such devices need to be tested frequently to make sure they still have full power, and replace or recharge the batteries when they run down, but with a spring-based system, in principle "you could stick it on the wall and forget it," Livermore says.

Livermore says that the springs made from these minuscule tubes might find their first uses in large devices rather than in micro-electromechanical devices. For one thing, the best uses of such springs may be in cases where the energy is stored mechanically and then used to drive a mechanical load, rather than converting it to electricity first.

Any system that requires conversion from mechanical energy to electrical and back again, using a generator and then a motor, will lose some of its energy in the process through friction and other processes that produce waste heat. For example, a regenerative braking system that stores energy as a bicycle coasts downhill and then releases that energy to boost power while going uphill might be more efficient if it stores and releases its energy from a spring instead of an electrical system, she says. In addition to the direct energy losses, about half the weight of such electromechanical systems currently is in the motor-generator used for the conversion — something that wouldn't be needed in a purely mechanical system.

One reason the microscopic tubes lend themselves to being made into longer fibers that can make effective springs is that the nanotube molecules themselves have a strong tendency to stick to each other. That makes it relatively easy to spin them into long fibers — much as strands of wool can be spun into yarn — and this is something many researchers around the world are working on. "In fact," Livermore says, the fibers are so sticky that "we had some comical moments when you're trying to get them off your tweezers." But that quality means that ultimately it may be possible to "make something that looks like a carbon nanotube and is as long as you want it to be."

Tough and long-lasting

Carbon nanotube springs also have the advantage that they are relatively unaffected by differences in temperature and other environmental factors, whereas batteries need to be optimized for a particular set of conditions, usually to operate at normal room temperature. Nanotube springs might thus find applications in extreme conditions, such as for devices to be used in an oil borehole subjected to high temperature and pressure, or on space vehicles where temperature can fluctuate between extreme heat and extreme cold.

"They should also be able to charge and recharge many times without a loss of performance," Livermore says, although the actual performance over time still needs to be tested.

Livermore says that to create devices that come close to achieving the theoretically possible high energy density of the material will require plenty of additional basic research, followed by engineering work. Among other things, the initial lab tests used fibers of carbon nanotubes joined in parallel, but creating a practical energy storage device will require assembling nanotubes into longer and likely thicker fibers without losing their key advantages.

"These scaled-up springs need to be large (i.e., incorporating many carbon nanotubes), but those individual carbon nanotubes need to work well enough together in the overall assembly of tubes for it to have comparable properties to the individual tubes," Livermore says. "This is not easy to do."

Rod Ruoff, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Texas, adds that while the theoretical energy density of such systems is high, present ways of making carbon nanotubes are limited in their ability to produce highly concentrated bundles, and so "It appears to me that the 'low hanging fruit' here is to find important applications where the energy density on per weight basis outweighs the energy density on a per volume basis." But, he adds, if Livermore and her team are able to produce denser bundles of carbon nanotubes, "then there are exciting possibilities for mechanical energy storage" with such systems.

The group has already filed for a patent on the technology. Their work has been funded by the Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation Ignition grant and by an MIT Energy Initiative seed grant.