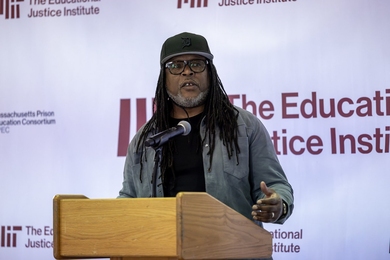

A panel of nuclear power experts met on Monday at MIT to discuss how to address nuclear waste recycling or disposal, which many analysts consider the biggest obstacle to building a new generation of nuclear power plants across America.

The meeting, convened by Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.), came on the heels of last week's decision by the Obama administration to end the planning for Yucca Mountain, Nev., as the final repository for high-level radioactive material from all of the nation's nuclear power plants. The planned facility had drawn strong opposition in Nevada, but some of the panelists questioned that decision and suggested that Yucca Mountain should at least remain as an option for possible use.

Carper, who chairs the Senate Subcommittee on Clean Air and Nuclear Safety, said that "over the last 30 years, the American public has dramatically shifted its views on nuclear power" and is now much more receptive to it as an option. But, he added, waste disposal is the "elephant in the room" in discussions of nuclear power.

"We need another Manhattan Project to figure out what to do with all of the spent fuel," he said. The 104 existing U.S. power reactors are expected to generate a total of more than 105,000 metric tons of high-level waste over their operating lifetimes, which under currently planned disposal methods would require a subsurface storage facility of more than 1,700 acres -- about twice the size of New York's Central Park. At present, all of the waste is stored at the sites of the plants that produced it.

All four of the panelists -- Charles Forsberg, director of the Fuel Cycle Study in MIT's Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, Matthew Bunn, associate professor of public policy at Harvard's JFK School of Government, Ernest Moniz, director of the MIT Energy Initiative, and Andrew Kadak, professor of the practice of nuclear engineering at MIT -- agreed that contrary to much public perception, the issue of waste disposal is not urgent. The present system of storing spent fuel in "dry casks" on the sites of the power plants can safely be left in place for several decades, perhaps even for a century, they said.

"There is no significant technological reason to implement permanent fuel disposal now," Moniz said. "We have time."

But deciding on the best policy for storing this material depends on reaching a clear decision as to what the nation ultimately wants to do with it, said Forsberg. "We do not know today if spent fuel is waste, or the nation's most important energy resource," he said, pointing out that current reactor operations, using a "once through" fuel cycle, only extract about 1 percent of the fuel's energy, and that it could be reprocessed to harness much more of that potential.

Deciding the best course of action for dealing with nuclear waste in the long run has at least as much to do with politics as with technology. "Siting and operation of a repository is as much an institutional challenge as a scientific challenge," Forsberg said. And Kadak suggested that even though President Obama has called for canceling the Yucca Mountain repository, "Yucca is still available. Do we really want to start over?" The process of studying and selecting that site has taken "a generation," he said, and starting again could create a similar delay.

Confusing the issue?

But Moniz cautioned that any effort to move toward nuclear fuel reprocessing today could seriously hamper efforts to stimulate the construction of a new generation of nuclear power plants. "The number one issue now is the first-mover nuclear plant construction," that is, the first new plant to break the more than 25-year hiatus in construction of any new plants in this country.

While new designs for safer, more efficient plants have been developed, it will require actually going through the process of permitting, building and operating the first new plant to convince investors the new systems are practical, Moniz said. "What will it take?" to get a new plant approved, he asked. "What will it cost? We don't know that yet." And, he said, "any discussion of moving to reprocessing now only confuses the issue."

Bunn added that even though reprocessing systems may be developed that would allow the efficient reuse of nuclear fuel, that is not the case today. Using today's reprocessing technology, he said, "I think it would be wasteful to proceed. Today, reprocessing is more expensive than not reprocessing," and also presents greater risks for nuclear proliferation and terrorism, and would actually decrease the nation's energy security.

"Those who are in favor of a new future for nuclear power should oppose reprocessing," he said. But, he added, things might change in the future if new reprocessing methods are developed: "Today, we don't know what the best fuel cycle might be down the road. Further research on advanced fuel cycles is called for."

Moniz said that MIT's in-depth study on the future of nuclear power, originally issued in 2003, said that in order to make a serious contribution to alleviating global climate change, the world would need new nuclear plants with a total capacity of at least a terawatt (or one million megawatts). With current policies, "we are not on a trajectory toward a terawatt," he said. A new, updated version of the 2003 study has just been posted on the MIT Energy Initiative's web page, he said.

What is most needed now, Moniz said, is "a robust research program on advanced fuel cycles" as well as other aspects of nuclear technology, totaling $500 million per year.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 20, 2009 (download PDF).