It's time for work toward sustainable development and sustainable energy systems to turn a corner, shifting emphasis from looking for possible solutions to taking action and finding ways to get those solutions implemented.

That was the message that emerged as more than 300 researchers and students from 16 countries around the world converged on MIT last week for the 12th annual meeting of the Alliance for Global Sustainability, a partnership that began in 1997 between MIT and three other major research universities with a technology focus.

In her opening talk to the three-day meeting, MIT President Susan Hockfield said the creation of the alliance "legitimized a whole new field," despite some initial resistance from people who felt that the whole concept of sustainability was "too elusive, too hard to define" and that universities were not the right place for such studies.

"It's impossible to ignore how much the landscape has changed" in the decade since then, she said.

Public attitudes on climate change have shifted dramatically, as reflected in the U.S. Congress finally taking action on new mileage standards for cars. Quoting New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, Hockfield said "green has become the new red, white and blue."

But along with the new awareness has come a wave of despair that must be overcome. As Hockfield said, "the public is starving for some sense of focus, clarity and direction. And I believe that the people in this room are well equipped to provide that leadership."

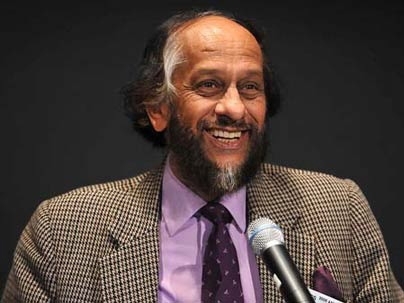

Among the many top researchers who addressed the group were leaders of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), co-winners of last year's Nobel Peace Prize, including three MIT faculty members. IPCC head Rajendra Pachauri, who gave the meeting's keynote speech, began by stating the scientific case clearly: "Climate change is unequivocal," he said, "and in the last 50 years the rate has been accelerating."

Climate change will continue for decades even if dramatic measures are taken now to reduce emissions, he said, and it will "impede present and future generations' ability to meet basic needs." Such changes will not be evenly distributed: "The poorest of the poor are left behind," he said, "but even the richest countries in the world are not immune from these effects."

Despite claims by some leaders that efforts to curb emissions will be too costly, Pachauri said, the most stringent measures-far beyond those proposed so far-needed to stabilize carbon dioxide levels at below 535 parts per million (compared to today's 380 parts per million) would have quite modest costs, "reducing the growth rate of nations' gross domestic product by less than 0.12 percent." Because of the many new business opportunities that would be created by such measures, he said, "it might even turn out to be a negative cost-that is, a gain."

And there could be additional gains at the same time, he said: "Increased energy security, health benefits from reduced air pollution, more rural development, increased agricultural production and reduced pressure on natural ecosystems."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 6, 2008 (download PDF).