Ask most Americans where their electricity comes from and they'll say, "From the wall." They don't tend to think about the country's energy infrastructure or how a hurricane or terrorist attack could disrupt it.

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) is thinking about these things. The institute was created after a massive 1965 blackout in the northeastern United States revealed the vulnerability of the nation's electric grid. EPRI, not a government agency and not an arm of the utilities, develops technical solutions to industry issues as an objective outsider that raises its own funding.

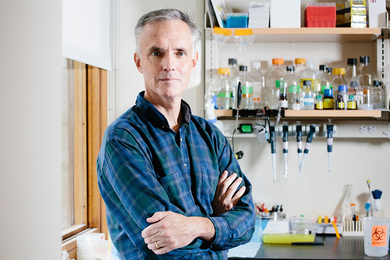

Theodore U. Marston, EPRI senior vice president and chief technology officer, spoke Thursday, April 6, as part of the Perspectives on Critical Infrastructure Systems series co-sponsored by MIT's Center for Technology, Policy and Industrial Development and the Engineering Systems Division.

Hurricanes, terrorists and hackers all have something in common: They are potential disruptors to a critical national resource.

The EPRI is reviewing all 103 U.S. nuclear power facilities for their vulnerability to natural and man-made threats, and eventually it will conduct risk analysis of the terrorist vulnerability of 17 sectors, including liquefied natural gas, subways, water supplies, dams and the power grid. The EPRI will advise the Department of Homeland Security on where to allocate funds to best protect these facilities.

Surprisingly, the institute has found that "nuclear plants have a low terrorist risk," he said, because of the nature of their design and the fact that few nuclear plants are in heavily populated areas. A rarely considered but potentially serious scenario is that of an avian flu epidemic, Marston said. Because symptoms don't appear for 24 hours, an individual could infect an entire crew, leaving a dearth of personnel to run a plant.

EPRI also tallied the lessons learned from the Gulf Coast following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, when high winds took down utilities' walls and blew asbestos from their thermal insulation "everywhere," Marston said.

The simple things caused the most trouble. Knowing who at the plant should stay and who should leave, making sure personnel were not denied access back into the plant by police, and getting in and out of electrical gates with no power are just a few of the unanticipated snags that could have been worked out in advance.

Bringing the aging industry into the 21st century is part of EPRI's challenge, Marston said. Until recently, there has been only minimal investment in electricity transmission systems. Power plant control rooms still feature "analog controls with levers and big dials," said Marston. "The question is, how can we advance the technology?" The solution lies in part with "intelligent systems" that monitor themselves and locate problems in real time, he said.

But there must be a "fair and equitable way to fund these upgrades," Marston said. "If you want cleaner, more reliable electricity, it's going to cost more. That's a fact of life."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on April 12, 2006 (download PDF).