Habits tend to be "friendly little fellows" that help us coast through the day, says Ann M. Graybiel, the Walter A. Rosenblith Professor of Neuroscience in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

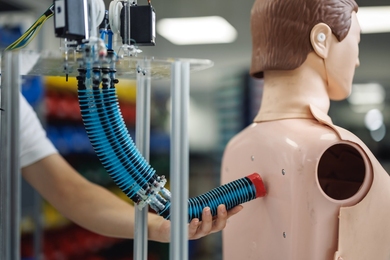

But the same loop in our brains that helps us perform tasks on autopilot can go awry, causing problems ranging from Parkinson's disease and obsessive-compulsive disorder to addiction. On Monday, Graybiel delivered the 31st Killian lecture, "The Robot Within Us: Neural Mechanisms Underlying Habit Formation."

Graybiel, a principal investigator in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, is recognized worldwide for her pioneering work on the architecture and neurochemical organization of the large forebrain region known as the basal ganglia.

"Even though it's buried under the cortex, the main output of the basal ganglia is to supervise the 'big boss' lobes of the cerebral cortex," the brain's executive responsible for the daily and long-term decision-making that shapes our lives, she said. A loop of signals and receptors help us select what to do and what not to do, and this system can be very powerful. This same loop is responsible for harmless rituals and uncontrollable, debilitating compulsions.

The basal ganglia house the brain's dopamine receptors, and dopamine is a potent reward signal. "We lurch somehow through life between rewards and punishments," Graybiel said. In conditions where the ability to take up dopamine is lost, such as in Parkinson's disease, behavior and cognition are profoundly affected. In addition, drugs such as cocaine target these receptors and send them into overdrive, causing physical changes in the brain that are hard, if not impossible, to reverse.

Graybiel, who attended Harvard as an undergraduate, peppered her talk with good-natured digs at MIT's proclivity for numbers over words. "The first thing MIT undergrads do when they get up is turn on the computer," she said. "After that, everything is optional." Of the cerebral cortex, she said, "It's a phenomenal organ. It's sort of an MIT organ. We spend a lot of our time not on the plane but on autopilot."

A 2002 recipient of the National Medal of Science, Graybiel earned a Ph.D. degree from MIT in 1971 and has been a member of the faculty since 1973. She joins an impressive list of recipients of the James R. Killian Jr. Faculty Achievement Award, established by the MIT faculty in 1971 to recognize "extraordinary professional accomplishments" by members of the faculty and to honor Killian, former president and chairman of the corporation.

"Ann Graybiel has had a profound impact on research on the functional anatomy and physiology of the brain," Stephen C. Graves, the Abraham Siegel Professor of Management and chair of the faculty, read from the citation before the lecture. "She is widely sought as a speaker because of the clarity and energy of her presentations and for her ability to make the complexities of the brain accessible to those who are not experts in the field."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 19, 2003.