Hundreds hear Charm School etiquette tips

About 800 students attended Charm School last Thursday, swarming through Lobbies 7 and 10 to attend 67 classes in 25 subjects, including three sections of "Buttering Up Big Shots" and four of "Dealing with People You Really Need in Life!"

Other popular courses included "Formalities, Flirting and Dating: Understanding Male and Female Perspectives," "Clothing Statements," "Table Manners," "Telephone/ Cell Phone/E-Mail/Network Etiquette," "Road Respect," "Courteous Cycling" and "How to Tell a Joke."

"Charm School has achieved its objective," Dean of Charm Travis R. Merritt said in the keynote address at Charm School Commencement, during which 150 "degrees" were awarded. "Look at the syllabus. There are no references to Dweeb Communications or Nerd Love. That's over. We've arrived. The stereotype of MIT students as style-deprived or ungraceful is dead."

The Chorallaries led the Commencement procession, playing Pomp and Circumstance on kazoos, and joined the student body in singing the Charm School alma mater. Dean Merritt led them in the Charm School cheer.

The day's highlights also in-cluded a game show entitled "Who Wants to Be a Charminaire?" in the Bush Room, hosted by Professor Emeritus Jay Keyser, and an exhibition by the Ballroom Dance Team in Lobby 13. Television channels 4, 5, 7, 25 and 56, the Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Cambridge Chronicle and Tab covered the event.

Charm School was coordinated and organized by Assistant Dean Katherine G. O'Dair and Heather A. Trickett of the Public Service Center.

Robert J. Sales

In batter's battle, perception is everything

"Keep your eye on the ball" is the Little League coaches' mantra. But while batting great Ted Williams might claim otherwise, a researcher at a January 20 IAP event says it's not physically possible to watch your bat connect with the ball.

Rob Gray, a research associate with Nissan Cambridge Basic Research, gave a talk called "Through the Eyes of a Tiger: Perception and Sport" sponsored by the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences. Dr. Gray presented an overview of experimental findings that explore athlete's perceptual skills and decision-making processes.

When researchers tested Ted Williams's claim that he could tell whether his bat smacked a ball on one seam, two seams or no seams, he got five out of seven right. But Gray said that the angle of the ball and hitters' line of sight diverge shortly before the ball reaches the bat.

"At around six feet from the plate, [professional] batters lose sight of the ball before the critical moment when it crosses the plate," he said. Amateurs lose sight of the ball 10 feet from the plate. Professionals could move their eyes faster than amateurs and they also moved their heads to follow the ball, while amateurs moved only their eyes. But based on the ball's trajectory, all hitters can and do attempt to predict where the ball will be as it crosses the plate.

When you think about the physics of trying to predict where a three-inch-diameter sphere hurled at you at 80-100 mph will end up so you can hit it within about eight inches of bat space, it's a wonder that anyone manages to hit the ball at all. "It's impossible to follow a 100 mph fast ball with your eyes," Dr. Gray said. "The ball moves at 1,000 degrees a second and our fastest eye movements are 90 degrees a second."

But players hit the ball all the time. They use a skill called judging "time to collision," or TTC. Our brains rely on five factors to help us see: color, brightness, texture, motion and stereo vision. Size is one of our strongest cues in TTC: as an object approaches, it looks bigger. The rate of change of an object's perceived size gives us a sense of the time left before it reaches us. In addition, a near image forms a different kind of image on the eye than a faraway image, Dr. Gray said.

He said not to underestimate the importance of depth perception provided by our binocular, or stereo, vision. When batters were given vision-blocking lenses to wear over one eye, their accuracy dropped dramatically. Lenses over two eyes had no effect.

Judging how high the ball will be when it crosses the plate is essential for accurate batting. Based on the reality of gravity, a ball must fall as soon as it leaves the pitcher's hand. What tells a batter that a pitch is a 90-mph fastball rather than an 80-mph curve? A slightly slower pitch will fall a critical half-inch farther when it reaches the plate. "You don't have the information you need to know where the ball will cross the plate," Dr. Gray said. "The only information you have is angular. You have to make a guess."

Although batters have an amazing ability to distinguish a fastball from a curveball (90 percent accuracy with only a 200-millisecond glance at the spin of the laces), sometimes they say that the ball dropped or rose dramatically at the last second before reaching the plate. Dr. Gray said this is an illusion caused by misjudging the ball's speed. If you expect the ball to be at a certain height when it reaches you, it might seem as though the ball has suddenly switched course when you correct your initial perception.

In addition to relying on perception, batters also use physical cues: how much white they can see in the pitcher's hand sometimes tells them whether he's planning a fastball or a curveball, or his arm and leg motion can give him away. Dr. Gray said that for this reason, Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez has trained himself to make his windups identical. Pitchers with unusual deliveries tend to be successful for a while because batters have trouble keeping their eyes on the release point, or the point where the ball leaves the hand. Some pitchers strategically place their white resin bags on the mound so that from the batter's view, it will look like the ball came out of the bag.

Batters get some advantages as well. Seats in center field directly behind the pitcher are often covered with a black tarp to prevent fans in white shirts from distracting the batter. Pitchers are the only players required to use a black or brown glove to provide high contrast to the white ball.

Deborah Halber

'King Louie' triumphs in robot contest

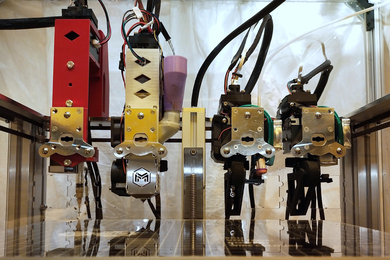

"King Louie," a long-armed, knuckle-dragging robot made of blue and red LEGOs, ruled over a veritable animal kingdom of robots in the final rounds of the annual IAP Autonomous Robot Design Competition (6.270) on January 27 in the sweltering confines of Rm 26-100.

The contest, called "Bots in Blue," took place on two pingpong-table-sized MIT "campuses." These were painted with areas to denote Massachusetts Avenue, East and West Campuses and "jails" at opposite ends. Teams scored points by putting small black blocks ("hackers") into one of the jails; by moving white blocks ("students") into their own side of "campus," and by pulling pink blocks ("professors") out of the traffic.

"King Louie," named in honor of the character in The Jungle Books, ruled over other crowd-pleasers inluding "Smackdown," "My Little Pony" and the mysterious "Uncle S." "Louie" relied on an element of reliable surprise -- two long, red LEGO arms swept upward, outward and down upon the little blocks -- no mean feat in a contest that had been bedeviled by technical problems.

Campus Police put in a brief appearance at the start of "Bots in Blue," as well: people crouching on the steps created a fire hazard, and many were encouraged to watch 6.270 in an overflow room (34-100). The event was simulcast by MIT Cable and filmed by the BBC.

Contestants work in teams of two or three. In early January, each team is given the same kit containing sensors, electronic components, batteries, motors and LEGOs. They have three weeks in which to transform the parts into a working robot.

Sarah H. Wright������

Students become an art installation depicting race/gender experiences

Guillermo G������mez-Pe�a (right) offers pointers to actor Rishard Chen, a sophomore in chemical engineering, in his part of the theater piece that Mr. G������mez-Pe�a is directing later this week. Photo by Donna Coveney

The Ethnographic Museum of Irrelevant Races (EMIR) -- a temporary installation of satirical "living dioramas" produced by Dramashop students and directed by internationally known performance artist Guillermo G������mez-Pe�a -- opens Thursday, Feb. 3 in Kresge Little Theater.

Mr. G������mez-Pe�a is an artist in residence at MIT through the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Professor Program.

Associate Professor Brenda Cotto-Escalera of music and theater arts called the installation "a provocative work which will engage students and the public in valuable civic dialogue on the subject of race and its place in our history."

The "objects" in the mock museum are the MIT students themselves. The group worked intensively with Mr. G������mez-Pe�a during IAP to develop their own "hybrid personas," combining elements of local culture with their personal experiences of race and gender. The eight students will present themselves as "living specimens" complete with "unique artifacts" in individual dioramas.

Unlike the dioramas typical of ordinary musuems, the "specimens" in EMIR will converse with visitors, who are encourged to interact with the "installation."

EMIR "specimens" include an Indian-American woman trying to balance her "restrictive and pious Bengali-Indian culture" with the "liberal but prejudiced US culture"; a white, Appalachian lesbian "adrift in the privileged liberal world of Cambridge, Massachusetts"; and a man of Arab ascent who is "robbed of any identity other than that of dirty Muslim terrorist wife-beater."

The EMIR installation also features a video introducing the audience to "radical interpretations of culture based on race, hegemonic principles, covert ideology and social construction" and a museum shop containing inexpensive artifacts of the exhibit's unique environments.

Active as a multimedia performance artist, social and cultural critic, author and NPR commentator, Mr. G������mez-Pe�a explores cross-cultural issues and identity, often through fictionalized, interactive dioramas that parody various colonial practices of representation.

Public viewing periods for the installation are: February 3, 4, 5 and 7 from 7-8:30pm and 9-10:30pm, and February 6 from 1-2:30pm and 3-4:30pm. Admission is $6 for students and senior citizens and $8 for the general public. For reservations and information, call x3-2908 or e-mail emir@mit.edu or see the EMIR web site. There is adult content in the installation; parental discretion is urged.