Tod Machover's dream is to make everyone a musician. Not necessarily through mandatory piano lessons-though the MIT composer/inventor studied cello and received bachelor's and master's degrees in composition at Juilliard-but through the marvels of cybertechnology.

Mr. Machover, associate professor of music and media in the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, took a giant step towards his dream this week when his one-of-a-kind interactive musical event, Brain Opera, opened at the first Lincoln Center Festival in New York. The multimedia work-one of the largest interactive entertainment projects ever undertaken-will have nearly 100 free performances and involve a cast of literally thousands during its premiere, which runs until Saturday, Aug. 3.

Developed by Professor Machover and a team of more than 50 artists, scientists, musicians and inventors from the Media Lab and beyond, the project features opportunities for the public to interact with computer-enhanced "hyperinstruments" and computer-interactive programs as observers, contributors and participants. Brain Opera will premiere simultaneously on the Internet; those wishing to pay a virtual visit to

Following its Lincoln Center premiere, Brain Opera will travel to Copenhagen, Berlin, Tokyo, West Palm Beach, FL; Singapore and Linz, Austria, with many additional sites being scheduled through spring 1998.

The work consists physically of three parts, each occupying a separate space in the Lincoln Center complex. The first is a large interactive display, responsive to crowd presence and movement, which is located outdoors on the Lincoln Center plaza, reflecting on-site and Internet Brain Opera activities.

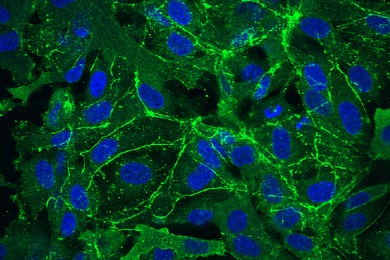

The second is a maze of "interactive music/image experiences" using Professor Machover's state-of-the-art hyperinstruments-"intelligent" music instruments which use computer technology to expand the capabilities of instrument and performer. Here, in the lobby of Juilliard's Morse Recital Hall, visitors can move their fingers across the touch-sensitive pad of the Melody Easel to "draw" computer-generated melodies. Or, in Harmonic Driving, they can navigate through a composition using a steering wheel, joystick and foot pedal to alter the flow and texture of the music depending on what path is taken.

The third part is a final performance space, where the music and sounds created by the audience in the lobby, along with contributions from the Internet, will be woven into a single, coherent 45-minute multimedia performance.

Professor Machover has been developing Brain Opera with his collaborators for more than two years, but he's really been working towards this project for over a decade. His work with hyperinstruments began at the Media Lab in 1985, as he partnered with musicians such as cellist Yo-Yo Ma and pop artist Peter Gabriel in an effort to enhance the capabilities of instruments for virtuosic professionals. In 1991, his Hyperinstrument Group began creating sophisticated interactive musical instruments for nonprofessional musicians, students and music lovers. These inventions included devices such as the Joystick Music System, which allowed the user to guide and shape the evolution of a musical work by moving two videogame-type joysticks in a sort of "musical driving" game; and a Sensor Chair, designed for magicians Penn and Teller, which used an invisible electric field to detect body motion and turn it into sound.

Professor Machover hopes that Brain Opera will be many things: a powerful artistic experience; an exploration of the mind and of the creative process itself; an example of how technology can be used to enhance expression, encourage communication and build community; a synthesis of art, technology, psychology and science; and an introduction to a new kind of music that could bridge the chasm between classical music tradition and the John Cage-ian avant-garde.

Most importantly, he hopes that it will be many things for many people-a mechanism, according to the prospectus, for bringing expression and creativity to general, non-specialized audiences "on site or at home, by combining an exceptionally large number of interactive modes into a single, coherent experience."

While the cables and cameras, sensors and screens, microphones and MIDI applications have been envisioned and assembled by Professor Machover and his team, the central concept behind Brain Opera is based, he said, on the work of his Media Lab colleague Marvin Minsky (Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences) and Professor Minsky's book The Society of Mind. Writes Professor Machover: "Marvin Minsky is the first person I ever met who dared to ask questions about music so basic that they seemed naive, yet so perceptive that no one has yet answered them. Why do we like music? Why do we spend so much time with an activity that has little or no practical benefit? Why does music make us feel? And think? And are feeling and thinking the same? Is music the activity that most deeply unifies our complex selves?"

Professor Machover hopes that the experiences in Brain Opera will stimulate audiences to reflect on questions like these. One of his greatest hopes, he says, is that it will "encourage people to be excited by their own minds" and by the desire, in the words of Professor Minsky, to "look inside and hear what is going on." It is this type of audience involvement-combined with the vocal texture of Brain Opera, the diversity of its participants, and its "dramatic progression" from a maze of complex fragments to a cohesive experience-that makes the work an "opera," Professor Machover said.

Whatever the genre in which one wishes to place it, the event has already attracted international media attention and the curiosity of professional musicians, amateurs and non-musicians alike.

In conjunction with Brain Opera, on Thursday, July 25 in Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall, Professor Machover will present his "Hyperstring Trilogy," in which all three of his compositions for hyperinstruments will be performed for the first time on a single program.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on July 24, 1996.