Introduction

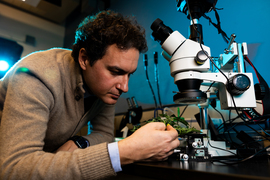

Benedetto Marelli is a biomedical engineer by training and a materials scientist. He is an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. His work is focused on using biomaterials-based innovation to improve agricultural methods, food security, and food safety.

In this episode, President Kornbluth speaks with Marelli about the advantages of using silk-based coatings in agriculture and water filtration, and why being bold and creative can lead to powerful discoveries.

Links

Timestamps

Transcript

Sally Kornbluth: Hello, I'm Sally Kornbluth, president of MIT, and I'm thrilled to welcome you to this MIT community podcast, Curiosity Unbounded.

Since coming to MIT, I've been particularly inspired by talking with members of our faculty who recently earned tenure. Like their colleagues in every field here, they are pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Their passion and brilliance, their boundless curiosity offer a wonderful glimpse of the future of MIT.

Today my guest is Benedetto Marelli, an associate professor in MIT's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Benedetto's work focuses on using biomaterials-based innovation to improve agricultural methods, food security and food safety.

Benedetto, welcome to the podcast.

Benedetto Marelli: Thank you very much for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

Sally Kornbluth: So you do incredibly interesting work, and I really want to kind of highlight a number of things. First of all, hunger and food insecurity are huge global problems, obviously, with approximately 750 million people worldwide experiencing hunger on a regular basis. Benedetto, you're a biomedical engineer and a material scientist who works on making food systems more sustainable by using silk as a coating for both food preservation and to enhance seed growth. Why silk?

Benedetto Marelli: It's a very good question, and I'm still asking myself sometimes how I came up to this solution. The reality is that I did study biopolymers, which are the materials that nature uses to design life and for biomedical application, mostly for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Then during my postdoc, I came by chance with a discovery that these materials can be applied to food and can make membranes around food and extend the shelf life. From there, I discover a completely new world, almost overnight and a new frontier open in front of my eyes, and I was like, let's see what we can now do with these materials when we apply to food and agriculture. Because they were applied before to food and agriculture, but not with the lens of a biomedical engineer and so I started to look at the problems. So I started to, literally, go through literature understanding what were the big problems, the big challenges in the agri-food systems, and try to match the problems with solutions that my lab could create with these biomaterials.

To go back to your question, why silk? Silk is a material that is very ancient is almost 5,000 years old and is also entrenched with my history. I grew up in Milan, which is a big fashion city, and when I was doing my undergrad in front of my university, there was a silk institute where they were doing textile research. And so I did my Europe there-

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, wow.

Benedetto Marelli: ... and at the same time they were using silk for biomedical application. It was just the beginning of it. So I really got excited about using these materials, and I never gave up using it.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's fantastic. So you said you discovered that silk had this ability to be used in the context of food. You know, I heard there were maybe chocolate-dipped strawberries somewhere in this inspiration. Tell me a little bit more about how you sort of stumbled on the food connection.

Benedetto Marelli: There were. So the lab where I was doing my post-doc organized competitions where we had to cook with silk because silk is considered edible in many part of the world.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, I see. Interesting.

Benedetto Marelli: So I was coming back from a conference in Switzerland where I saw in the airport a lot of these chocolate-coated strawberries. At the time I was studying the optical properties of silk because silk we're experiencing it as a white fiber, but in reality, that's how the caterpillar, the silkworm makes it or the spider. Silk naturally makes films like defect-less film is monolithic materials that are transparent, really, really transparent.

Sally Kornbluth: I see.

Benedetto Marelli: So I was trying to embed on the surface of the strawberries optical gratings. So these are diffraction gratings, they look like a little bit the back of a CD or a DVD so that you could add this sort of eye experience...

Sally Kornbluth: I see, I see, a little shiny...

Benedetto Marelli: Exactly. To eat in your strawberries, but it failed. Like it never happened.

Sally Kornbluth: I see. I see.

Benedetto Marelli: So I left it on the bench and then I came back a week later and I saw that the half of the strawberries were rotten and were not edible, but the other were preserved. So I came back to the idea and I say why this is happening and that's how it started, right? So we started looking at the membrane properties of silk and how it works as a food coating, and that how everything started.

Sally Kornbluth: That's great. It's like your penicillin moment. It's funny because I always think about this. You're always told to keep all your research materials neat and clean up right away, and there are a lot of things that come up with while I left it on the bench and came back a week later, and it was like, aha.

Benedetto Marelli: It's what I keep saying to my students. I tell them when they're in the lab, you have to be very neat and you have to respect the lab as a neat working environment, but be playful. And if you're a little bit messy, it's fine because typically that's how new discoveries may come.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly, exactly. Have you either yourself worked on or are you aware of other coatings that people use, natural coatings that work in a similar way, or even synthetic coatings that people are developing?

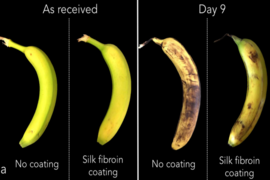

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah, there are other coatings. So we're not the only one in the world that did that, and this is a good thing. There are other coatings, there are other companies that make edible coatings. Some of them, like everybody probably who lives in the United States experience apples that sometimes are coated with waxes and that's to extend the shelf life. So that's the typical food coating when it comes to mind.

There are pro and cons with the different coatings. The beauty of silk and why it works so well is because we can use just a tiny amount of material, very little amount because it makes very thin coatings that are very good in keeping the water in the food and the oxygen out. And so that's key to extend the shelf life, typically.

Sally Kornbluth: I see. So food preservation in general then is keeping air out, keeping water in.

Benedetto Marelli: I would say so. For some foods, yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: Got it. So your seed coating was recognized as one of the inaugural projects of MIT's Climate Grand Challenge. Ultimately, how do you see this addressing problems of hunger and food insecurity in the context of climate change?

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah. So that's a project that is led by Chris Voigt, and I think we were a good cohort of MIT PI's professors who are working all together from different angles to try to make agriculture more sustainable and revolutionize fertilizers. So as we are developing innovations in the lab, we have an eye of rapidly translating the technologies in different markets, and so we're now looking at making field experiments in different part of the world. Plants are stressed by different, what we call abiotic stressors, so this can be salinity of the soil, scarcity of water, excessive heat, and these biofertilizers that we're developing are microbes that boost the plant health. So we are engineering the interface between the microbes and the plants and so we're now trying to translate the technology by doing field experiments and see how far we can go.

Sally Kornbluth: I see. So you're working directly with farmers now?

Benedetto Marelli: Yes.

Sally Kornbluth: That's really interesting. The other thing that I think is really interesting, just in terms of environmental health, is the notion of using silk as a material to filter out contaminants. So tell me a little bit about that. So how's it different from traditional filtration methods? What are the advantages, and where do you see this going longer term?

Benedetto Marelli: So something that always amazed me about these biopolymers is that, thermodynamically, they want to come together to make nanomaterials. So that's really nanomaterials for free. You just have to take food waste or the waste from the paper industry or other industry that use natural polymers, extract the raw materials, and then engineering how they can come together to make nanofibrils.

Nanofibrils are very good for several application because they have a very high surface-to-volume ratio, so they can make a lot of interfaces with the environment. So we discovered that if you pass water through nanomembranes made out of silk and cellulose, we're able to extract forever chemicals from the water and some heavy metal contaminants. They perform extremely well. They perform similarly, if not better, to existing standard.

The big advantage I think is that, first of all, we take a waste material and is transforming a technical material. And on top of that, these membrane are biodegradable. So the moment we extract the forever chemicals, then we can simply degrade the membrane, take the forever chemicals out, and then dispose them according to the laws, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Makes sense. You don't compound the problem with a forever membrane.

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah, you don't want to create a new problem-

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly, exactly.

Benedetto Marelli: ... by solving another problem.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, I mean it's clear now that we're all carrying around a burden of many, many chemicals over a lifetime of consuming what are minor contaminants in any individual food or drink, but over the long haul are probably accumulating in our tissues.

Benedetto Marelli: And this is a challenge that we will need to face in the future. So as the humanity addresses new technologies, we need to engineer new technologies that take care of what inherited from the past, right? So I think we discover so many new technologies in the past, which has a huge beneficial impact on the human health, but now we also need to think about the planetary health and so how we can develop new technologies that complement the existing one, but also mitigating the impact.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly. You know, we recently announced, MIT recently announced our initiative on climate change, and the whole notion we have the climate project at MIT is we're going to have very focused missions on different areas of science, technology, policy, et cetera, that will be focused on solving particular problems, whether it be decarbonizing industry or building more resilient cities. We made one called Wild Cards because, in part, we don't know what's coming down the road, and we want to make sure that everyone's really interesting creativity can be incorporated into this project directed towards solving what I think is one of the most significant problems of our time.

You've been recently announced as one of our mission leads of Wild Cards thinking about unconventional solutions. So I'm just wondering, is it too early to hear a little bit from you about this mission, what kinds of projects and how you think about moving things forward?

Benedetto Marelli: I think I'm starting to have an idea of how the Wild Card will look like. First of all, it's going to be a place where serendipitous innovation will find the right place to grow and to thrive. And at the same time, we're going to try to push technology from what we call the proof of principle to the proof of concept. So we're going to try to take technologies that are almost ready, that have been already developed at the institute, and they need a final push so that they can have an impact on society, typically by spinning out or by being licensed.

At the same time, we're going to have a very open communication and channel with policymaking, and we're going to have stakeholders be part of innovation realm so that they can give the innovators a very early stage feedback of how the innovation could have an impact in the real world. So we're going to try to merge solution and problems in a single mission so that we can accelerate this innovation, and we can really push it forward.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that sounds great. I mean, I think there are so many fantastic ideas that are going to be emerging and thinking about how we essentially select the best ones and help them expedite a move into real use, I think, is going to be critical.

Benedetto Marelli: Absolutely. Then something we're also going to try to do is typically when you spin out a company, eventually the company needs to survive. So it's going to look for market, and it's going to look for making money. This is natural, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Benedetto Marelli: But at the same time, we can try to develop innovation that while it's chasing the money-making solution, it will also chase solution that have an impact in the real world where is needed the most, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Benedetto Marelli: These are typically hotspots for climate, hotspots for population growth. So can we develop in parallel the same innovation so that it can bring us solutions that target two completely different market? So a profitable market and a less profitable or maybe not profitable at all market, but using the profit of the profitable market to sustain the non-profitable one. I think that would be a good model.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah. Also the non-profitable one, as you say, provides proof of concept that these things can actually be deployed, and so that will attract more investment for those who are interested in the for-profit side.

Benedetto Marelli: Absolutely, absolutely. At the same time, these are the non-profitable market providers also a possibility to develop technologies that are low-tech, that are simpler. So also mentally it's very challenging to make technology that looks simpler and is more accessible. So I think it would be a good exercise also for the innovators.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, I mean, you raised something that I think is really important about the climate project at MIT, which is it's one thing to address some of these problems in the United States, often in a more high-tech, high-cost way. But one of our goals is to make these technologies affordable, deployable, usable, because the impact on climate, we all share. I mean, I always joke that changing climate over Cambridge isn't going to do us a whole lot of good. So I think that's right. If we can find a way to reduce cost, make it easy to use, that will go much further in terms of potentially having an impact.

Benedetto Marelli: Absolutely. And I had the first-hand experience on this when I, in the project on the seed coatings, we're applying some of these seed coatings in Morocco where we are deploying them in farms, in experimental farms, in Morocco, in collaboration with local universities. And we do have the stakeholder's feedback at the very early stage, and they really help us in developing solutions that can be deployed very rapidly because-

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's great.

Benedetto Marelli: ... if we close ourselves in the basement of Building 1, we don't know what the farmer in Morocco really needs, right? So having their feedback early on is very important.

Sally Kornbluth: That's right. I mean, I think our partnerships with local, whether it be farmers or NGOs or local industry, I think is going to be important.

You have a company called Mori. Is that operating? How's it being used commercially, et cetera? Maybe you can tell me a little bit about that.

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah. So I co-founded the company, the company grew up out of my postdoctoral research, and then it was spin out when I was at MIT. And I think for me was the best way to really see my technology going out and having an impact in the real world. So I'm very proud that there are people that now working in the company and my original idea actually having an impact in the real world. And when I go to the grocery store and I see food that is coated with the materials that I develop, of course, it makes me very, very proud.

Sally Kornbluth: So I have a really silly question to ask you. So in terms of the production of the silk you use, what does that look like? In other words, are you using natural methodologies? Are you synthesizing it?

Benedetto Marelli: So silk can be used both, can be made both through synthetic biology, or the one that we're using is extracted from the cocoon of the Bombyx mori caterpillar. For food application, it has to be approved by the FDA, which made the silk generally recognized as safe material, so an edible materials for the intended use of food coating. So we simply get the cocoons, and then from the cocoons we extract the protein, and then the protein is applied directly on the food.

Sally Kornbluth: I mean, how does this scale up? In other words, do you have a huge farm where you're got caterpillars making cocoons? How do you come by all this material?

Benedetto Marelli: So we retrofit the sericulture system so some of the cocoons that are supposed to go to the textile industries, they actually come to us because they've been produced to satisfy the regulations of the United States for food safety. Then once we receive them, we treat them in the United States, and then we apply the coating at the farm level.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, interesting. Very interesting. It seems that Boston now is experiencing a growing cluster of food tech companies. Have you interacted with any of the other efforts that are developing here?

Benedetto Marelli: I did over time, and I must say when I joined MIT in 2015, it was not such a big food cluster as far as I know. And when I was going around saying, "Oh, we can use silk to prevent food loss and food waste," people were looking at me in a weird way. Then over time, I think it grew that the biomedical industry and the innovation in biotech could actually have a big impact in food and agriculture. So Boston became a hub. And so I was fortunate in that sense that it was matching the same time when the company came out. And I think there's a good cluster of people that is growing, and there's a lot of idea that are exchanged. And the students, MIT students, they really want to have an impact in food and agriculture. So they realize that is a major societal problem, first of all, because not everybody have food. We're also wasting too much food, right? So the food that we waste can feed 1.6 billion people.

Sally Kornbluth: Wow.

Benedetto Marelli: It depletes 25% of the fresh water.

Sally Kornbluth: Wow.

Benedetto Marelli: So that's a societal problem. And so students are really, particularly MIT, are really passionate about this problem. They really want to go there and make a difference and move the needle, right? So they're very eager to find solutions, and they take classes around MIT, and they're looking forward to solve this problem. So it's very interesting. It's a very, very vibrant community that is keep growing.

Sally Kornbluth: That's terrific. Backing up a little bit now from your time here, you studied in Milan, you studied at McGill, you studied at Tufts before you landed in MIT. Tell me a little bit about the journey and what actually brought you MIT, specifically.

Benedetto Marelli: I still want to know if I'm the only biomedical engineer who's a professor in the civil environmental engineering department. I don't think there are many.

Sally Kornbluth: Maybe not, maybe not.

Benedetto Marelli: And I think that's the beauty of MIT. I think bringing me to MIT was the vision of the former department head, Markus Buehler who works on silk so we had that connection. And I have to say also my interest in food and agriculture and the understanding that this could become my career also, Markus had a big role on that because I remember the first time I was presenting my research, when I talk about food, his eye shot open, and he looked very interesting, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Benedetto Marelli: He was like, "Oh, this is not the usual silk research." So that told me something. And what I noticed at MIT is that everybody was not skeptical, right? They embraced, come in and say, look, we can use silk for food and agriculture. They were encouraging me to do so. They gave me good advices. They paired me with many mentors in the senior faculty that could help me developing the technology and thinking how to critically solve problems. So I think it was very instrumental, if you like, for my research and for my success and the success of my students, particularly.

Sally Kornbluth: You know, two things you said resonate. One is the impact of mentors and mentor reactions, you know? Sometimes it just takes that spark of encouragement to think this is not a completely crazy thing, that it's important pathway to follow.

The other thing is, as you're talking about it, I'm thinking about you as director of the Wild Card part of our project, and the notion that you're going to hear these kinds of things that'll sort of spark entirely new areas. And they might sound crazy a little bit sometimes, but MIT is sort of the place where crazy becomes the norm kind of thing.

Benedetto Marelli: Absolutely. And you need to be bold and you need to remain creative. And when the two merge, typically good things can happen.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly.

Benedetto Marelli: So I really hope in the future for the missions, I will have the same reaction that I saw in Markus-

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, exactly.

Benedetto Marelli: ... when some people are going to present me the research.

Sally Kornbluth: You know, I'm wondering where this sort of desire to make a world impact came from. What was your family like? Was this something that you remember growing up with, or something you developed later?

Benedetto Marelli: So I grew up in a very normal family, middle class family. I think what really sparked that I wanted to change the world, it came from almost my experience in the Boy Scout.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, really?

Benedetto Marelli: I had an experience in the Boy Scout when I was young, and they really taught me about having a positive impact on society and respecting the environment and being a steward for the environment and a good citizen. I liked the idea and from there, I started to have this idea that my work would actually benefit society. Of course, I never thought I would become a professor at MIT, but even in the small day-by-day tasks, I always try to embrace that vision.

Sally Kornbluth: What do you like to do if you have a day off?

Benedetto Marelli: I like typically to play with my kids. They both play soccer, so we play a lot of football or soccer together.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes, yes. That's nice.

Benedetto Marelli: And I like to use my motorcycle. So I'm an avid motorcycler, and so I'm using a lot my motorcycle and I'm going around with it. So if you see me around MIT with a motorcycle...

Sally Kornbluth: Wow. Where do you go on your motorcycle?

Benedetto Marelli: From here, you typically go to New Hampshire, Vermont or to Rhode Island.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, nice, nice.

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah. In Italy you have much more options because I had the Alps close by, so those are very, very nice to drive, but yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: And maybe there's a limited time of year here or-

Benedetto Marelli: You're right. Unfortunately, yeah, is April till October. Sometimes I push it to November.

Sally Kornbluth: Where do you do your thinking? Do you think on your motorcycle or...

Benedetto Marelli: No, I have to be focused on the road.

Sally Kornbluth: Pay attention, yeah.

Benedetto Marelli: The plane, is incredibly the plane, and when I'm flying is where I have all my ideas. I'm very relaxed, and I don't watch movies typically, and I just take notes. And I think and I think and I think and eventually, some ideas come up. And typically, 99 don't work, but you need one that works, and that's the best part for me.

Sally Kornbluth: So when you're trying to come up with something new, you plan a trip?

Benedetto Marelli: Yeah. I'm flying several times, so yeah.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, that's great. So I've really enjoyed this conversation. I've learned a lot. I had never thought about silk before, and the notion of its sort of multifaceted use, and also just the notion of thinking really outside the box to come up with solutions to real-world problems. So I thank you very much for joining us here today.

Benedetto Marelli: Thank you very much for the opportunity.

Sally Kornbluth: And I also want to thank our audience again for listening to Curiosity Unbounded. I hope you'll join us again. I'm Sally Kornbluth. Stay curious.

Curiosity Unbounded is a production of MIT News and the Institute Office of Communications in partnership with the Office of the President. This episode was researched, written and produced by Christine Daniloff and Melanie Gonick. Our sound engineer is Dave Lishansky. For show notes, transcripts and other episodes, please visit news.mit.edu/podcasts/curiosityunbounded. Find us on YouTube, Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. To learn about the latest developments and updates from MIT, please visit news.mit.edu.

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you'll tune in next time for a brand new season when Sally will be talking with Dr. Giovanni Traverso about his work developing the next generation of drug delivery systems and treatments, and the implications that it has for the future of medicine. We hope you'll be there. And remember, stay curious.