Introduction

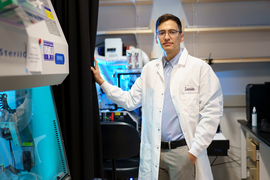

Sebastian Lourido is an associate professor of biology at MIT and a member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. Sebastian studies human pathogens and uncovers the genetic pathways that allow parasites like Toxoplasma gondii to survive and replicate inside human cells. His work could pave the way for new treatments for toxoplasmosis — which affects roughly 60 million people worldwide — and inspire drug discoveries for diseases caused by similar parasites.

In this episode, President Kornbluth and Lourido discuss toxoplasmosis, how parasites behave inside human cells, and the complex relationships that unfold over the course of a chronic infection.

Links

Timestamps

Transcript

Sally Kornbluth: Hello, I'm Sally Kornbluth, president of MIT, and I'm thrilled to welcome you to my podcast, Curiosity Unbounded. Here at MIT, our endless curiosity fuels a steady stream of inspiring discoveries and innovations. This podcast is your chance to join me as I talk with pioneers who are pushing the frontiers of knowledge and inventing real world solutions for a better future.

Today, my guest is Sebastian Lourido. Sebastian is an associate professor of biology here at MIT and a member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. Sebastian studies human pathogens and uncovers the genetic pathways that allow parasites like Toxoplasma gondii to survive and replicate inside human cells. His work could pave the way for new treatments for toxoplasmosis, which affects roughly 60 million people worldwide and inspire drug discoveries for diseases caused by similar parasites. Sebastian, welcome to the show.

Sebastian Lourido: Thank you, Sally. What a delightful opportunity to share our research with you today.

Sally Kornbluth: Fantastic. So, you've said that your work grows out of a fascination with how different organisms coexist. What does that mean in the context of parasites and how does it shape the questions that you ask in the lab?

Sebastian Lourido: Yeah, I think I have from an early age in some of the early exposure in undergrad to different questions in biology, a fascination with how different organisms clash, different natural histories with very, very distinct adaptations, all of a sudden coming together in a process of an infection and using different tools to adapt to very different niches to what we typically think about as free living organisms out in the wild. And so, for me, I think there was an intrinsic fascination in that clash, but then furthermore, an intrinsic fascination with being able to observe that under the microscope.

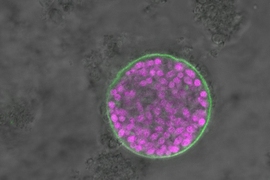

And because parasites are among the largest pathogens that infect humans, we can readily observe the process of infection, of parasitism, of intracellular replication inside of human cells under the microscope. And that really just captured my imagination. Moreover, in this class of organisms that we've decided to study, there's so little known about their fundamental biology. They've led a very distinct natural history from the branch of life that gave rise to animals and gave rise to fungi. And so, many of the lessons at a molecular level that we've gleaned from studying those other organisms are not really applicable to these organisms that have followed a very distinct evolutionary history.

And so, there was so much unknown. I kept asking professors and colleagues what we knew about how this process happened and how that process happened, how parasites enter cells, how they draw nutrients from those cells, how they decide between when to replicate and when not to. And all of those questions seemed vague and unanswered. And so, it just seemed like a really incredible area to go into research in. And also the impact that that research could have and the lives of people suffering from infectious diseases just seemed like a wonderful thing to devote myself to.

Sally Kornbluth: No, that's great. I mean, this is far from the public conception of parasites in horror movies. Although the word parasite, I guess, implies an interaction that may not be great for the host, unlike when we talk about symbiosis, things both benefiting mutually together. This is, as you said, the parasite hijacking, if you will, host functions. And I assume that that made it harder to study as well because a lot of the biology is not just intrinsic to the parasite, it's what the parasite will elicit from the host.

Sebastian Lourido: That's absolutely correct. I mean, I think that we can take that at several layers. Many of the parasites that we're interested in only survive, only replicate inside of a host, and that distinguishes them from maybe some of the bacterial pathogens that can be in some cases propagated in vitro in a flask. And so, that has an inherent challenge that lays obstacles in terms of genetic manipulation, understanding of molecular biology and biochemistry. All of the things that have been much more accessible in free living organisms are indeed challenged by these natural constraints of the system.

Sally Kornbluth: We don't think about that probably as much as we used to now that there have been so many innovations in molecular and cellular biology, but a lot of discoveries were using systems that were predicated on the fact that they were experimentally tractable. And so, dealing with something that's out of view, hidden inside the host that you have no way to propagate in vitro could be very, very challenging.

Sebastian Lourido: It's a major challenge. And certainly some of the major advances have been, how do we bring that as close to an in vitro system as possible? So, in our lab, for instance, in the case of Toxoplasma, we can maintain cultures of that parasite by infecting human cells in vitro and propagating it that way. And certainly one of the advantages of Toxoplasma is that it is relatively long-lived outside of those host cells. Even though it doesn't replicate, we can still manipulate it genetically. We can still change and observe elements of its physiology before putting them back into culture in those host cells, in those human cells in order to allow them to replicate.

So, there are still other barriers for the study of other organisms. And there too, I think there's this advantage of relying on those particularly closely related representatives that are more tractable. And that's been the case for Toxoplasma in this broader group of organisms called the Apicomplexans, which of course include many other human parasites such as the ones that cause malaria, some that cause diarrheas, and particularly intractable diarrheas in young children in developing countries belonging to the genus Cryptosporidium, and then other emerging diseases actually right in our backyard in New England, such as babesiosis, which is a tick transmitted relative of Toxoplasma. So, many, many diseases that can be in some subtle ways modeled back in the biology of Toxoplasma, which also motivates our research.

Sally Kornbluth: That's very interesting. And sadly, we're going to see more of those parasitic infections arising with climate change, et cetera, and with close juxtaposition of farm animals, agriculture, et cetera, to humans in different areas. So, let's talk a little bit about toxoplasmosis. For listeners who may not be familiar with it, tell us what it is, what effects it can have. My most recent reading at toxoplasmosis was probably 33 years ago when I was pregnant with my first child and was worried about toxoplasmosis. So, maybe you can tell us about it.

Sebastian Lourido: And what did they tell you then?

Sally Kornbluth: Not to change the cat litter. And that was great because I had my husband always changing the cat litter.

Sebastian Lourido: And it probably stayed that way for a few years.

Sally Kornbluth: Forever.

Sebastian Lourido: It was just to be safe.

Sally Kornbluth: As long as we had cats. Anyway.

Sebastian Lourido: Yeah. So, the reason that you were told that is because Toxoplasma has a special interaction with the cat. When a cat becomes infected with Toxoplasma, which occurs through the consumption of maybe a mouse that was itself infected with the parasite, the cat can allow for the sexual development of Toxoplasma. So, there are specific parasites that can live by replicating asexually, just dividing and making more copies of themselves, or sexually by making male and female a sexual stages that then fuse together to produce diversity and through sexual recombination.

And so, in the case of Toxoplasma, that sexual recombination only occurs in felines, and the product of that sexual recombination are these very environmentally resistant stages that are exquisitely infectious to us. Probably just a few, a handful of these stages coming into contact with our food and with our water are sufficient to infect a human being. And then in the context of a human being, what we would consider an intermediate host if the cats are the definitive host, these parasites can go from our intestines and disseminate throughout our bodies. In most instances, our immune systems are really good at keeping those parasites under control, although they never clear them actually. So, it's an interesting fact that of all the people who have become exposed to Toxoplasma, probably most of them carry the parasite chronically inside their tissues and that's something that we can discuss.

Sally Kornbluth: So, is that a problem for a subsequent pregnancy then?

Sebastian Lourido: It wouldn't be because you already have the immune responses and only the acute stages that are developing during that initial encounter are capable of traversing the placental barrier and infecting the developing fetus. That's the real risk. The other risk, which I think was really prominent during the AIDS crisis was that reactivation of the infection in those immunocompromised individuals could now allow the parasites to replicate unrestricted and damage all of those tissues where they were previously found late.

Sally Kornbluth: Where do they hide out?

Sebastian Lourido: They hide out in muscle and in the brain. And so, of course, that's a particularly susceptible place to have inflammation, to have tissue damage that can cause very severe diseases and even death.

Sally Kornbluth: So, when they reemerge, do they begin replication in vivo again? Is that the deal?

Sebastian Lourido: Correct. And in fact, a lot of our early work in my lab at Whitehead had to do with us understanding that cycle between them replicating and then bursting out of those cells. And that bursting out will damage, of course, the cells where they were previously replicating and cause tissue damage that alters a lot of structures in the infected organism. It's no good to have your neurons dying off, having immune cells infiltrating those areas, causing more inflammation, more damage. That process is predicated on parasite replication and host lysis.

Sally Kornbluth: It's interesting. I think there's a lot about this that we don't understand. So, for example, recently you probably saw the study that shingles vaccine is protective against dementia, presumably because the virus is lurking in your neurons for decades and decades and reemerges. I wonder if there's any possibility that Toxoplasma caused some late stage neurodegenerative disorders.

Sebastian Lourido: This is an active area of study and I think a fascinating direction, Sally. I think we don't understand what the long-term consequences of that interaction between the parasite and the host is. And it is one of my future aims to try to unravel the complex relationships that are carried out over the lifetime of a chronic infection. I think we've made a lot of headway in understanding some of the genetic circuits that mediate parasite differentiation from that acute state where they're replicating rapidly to the chronic state where they can lay dormant inside of our tissues. We've understood now what the master regulators of that process are at a genetic level.

One of our big breakthroughs was uncovering the basic elements of that circuit, but what are the long-term consequences of having those chronic stages there, replicating slowly, drawing nutrients from our neurons, and ultimately causing low levels of inflammatory responses that we really don't sufficiently understand. How's that changing brain physiology over the long term? I think that that is a really promising future avenue, and there are in fact associations epidemiological level between Toxoplasma seropositivity, which would be the production of antibodies by people who've previously encountered Toxoplasma and their prognosis in terms of neurodegeneration.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, very interesting. That's really interesting. So, maybe I was right to never change the cat letter again. So, just to clarify for the audience though, cooking meat thoroughly, taking care when cleaning the cat's litter box can reduce the risk, but what kind of treatments are available, especially for people who are immunocompromised?

Sebastian Lourido: Of course, I should preface this with saying that I am not a physician and that any sort of treatment should be in conversation with one's physician, but oftentimes people who are severely immunocompromised are maintained on therapies that kill the actively replicating parasites. But it is true that right now we have no therapies that are providing complete clearance of the parasites. And those chronic stages seem to survive every anti-parasitic drug that we have right now against them. So, when we think about Toxoplasma, we think about the suppression of tissue damage by killing off those acute stages, but not really a cure.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah. There might be a way to induce the replicative phase and then target with antiparasitics.

Sebastian Lourido: I think that's a brilliant idea. And certainly one of the reasons why we continue to try to unravel that circuitry that dictates differentiation. And so, we know in fact that some of the gene regulatory elements that we've found are required for parasites to enter the chronic state are also required for their maintenance of that chronic state. I see. So, if we could figure out ways of targeting those, we would definitely be able to transform the parasites into stages that we can treat actively and cure.

Sally Kornbluth: Very interesting. So, does Toxoplasma impact other species as well besides humans in terms of pathology?

Sebastian Lourido: Yes. And this is an interesting element of Toxoplasma compared to maybe some of its relative parasites, but it seems to be very poorly specific. It seems to have cracked the code of infecting any warm-blooded animal. And we find the same types of Toxoplasma that humans can get. We find it in chickens, which are also warm-blooded in mice, in rodents. We've previously documented the presence of these in alpacas and so

Sally Kornbluth: But they're not contagious from those species?

Sebastian Lourido: Only when the meat is consumed, right?

Sally Kornbluth: If it's not well-cooked.

Sebastian Lourido: If it's not well-cooked, correct.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, interesting. You mentioned a little bit about this serving as a model for other parasitic infections. Can you talk a little bit about that, how you would think about elaborating this work to other pathogens?

Sebastian Lourido: Yeah. I think that there are some conserved elements that are common to all of these parasites in the Apicomplexan group, and that includes the need to enter cells. There are both differences and commonalities in some of the machinery that's required for that entry process, and we've done some work in discovering some of those conserved elements. We've also been able to identify common elements of their cell biology. After all, they all share common ancestry and they essentially adapt it from the same free living ancestors as they undertook this path of parasitism.

And so, many of those elements are conserved, how they regulate their cell cycle, how they structure their cells, and the basic machinery that they use in order to start manipulating host cells. And then on the fringes of those interactions, maybe some of the specific receptors that they use to attach to host cells or the proteins that they're secreting into host cells to manipulate them, those tend to be quite a species specific because of course, they're under extraordinary selective pressure because the hosts evolve to try to suppress them.

Sally Kornbluth: It's interesting to think about how these parasites originally evolved.

Sebastian Lourido: There's some clues. And so, for a long time, I think since I've started working in Toxoplasma, I've been interested in that question as many of my colleagues, and there are some free living relatives that you could find maybe swimming around in seawater, maybe in association with corals, including some organisms that have only very recently been discovered as recent as 2010. Those organisms seem to have this facultative association with other cells, and there's in particular in some of these free living organisms, the propensity to attach to other single celled organisms...

Sally Kornbluth: But not get internalized?

Sebastian Lourido: ... suck out their insides.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, that's interesting. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Sebastian Lourido: As a source of food. We call this cellular vampirism.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I love it.

Sebastian Lourido: And so, one can speculate. Of course, it's difficult to recapitulate all of this biology, but one can speculate that that cellular vampirism all of a sudden went too far and established a much, much more intimate association between the vampire and its host, if you will.

Sally Kornbluth: So, maybe I should know this, but I don't. So, how easy is it to manipulate the genome of these parasites?

Sebastian Lourido: It differs between the different members of the group. In the case of Toxoplasma, I think we've been able to develop some of the best tools out of the entire group of Apicomplexan parasites, and that's what makes it such a robust model for molecular biology, biochemistry, and examination of essentially some of the fundamental elements of how these parasites work. We've been able to use the advent of CRISPR-based genome editing to perform genome-wide CRISPR screens that have individually mutate every gene... disrupting every single one of the 8,000 genes in Toxoplasma and asks what is required for infection of human cells or for survival of parasites under different condition for the acute infection that causes so much pathology.

So, that's been really transformative. And it has served also as a framework for work from colleagues that has attempted to do large screens in malaria parasites, for instance. And it's been really fascinating to be able to compare those large scale analyses of now different Apicomplexan representatives as they've come in online since our original CRISPR-based screening methods.

Sally Kornbluth: Very cool. That's very cool. So, has AI changed the way you're working at all?

Sebastian Lourido: There are maybe two ongoing initiatives that I'm really excited about and that overlap with the extraordinary promise of AI in biomedical research. The first one is that as we've developed our method to understand gene function by doing these large scale mutagenesis studies, we can observe each one of those disruptions as it plays out in the interaction with a parasite in living cells. This technology which has been developed through collaborations with Iain Cheeseman's lab at Whitehead and Paul Blaney's lab at the Broad have allowed us to get very rich phenotypes out of these perturbations that give us this grand look at all of the cell biology that's occurring in that interaction.

Sally Kornbluth: Even if you don't really know what the phenotype means, it's like a huge catalog of different phenotypes with different mutations that will allow you to predict behaviors.

Sebastian Lourido: Precisely.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Sebastian Lourido: And I think that that sort of technology has been very timely to the developments in AI-based image analysis, which allows us to capture ever more subtle differences between those infected cells, between those images of infected cells, and extrapolate that to comprehensive analysis of which genes must be operating together to coherently change the process of infection in a particular way. And so, there, I think we have this partnership between the generation of really broad-based data that gives us visuals on so many different perturbations and the algorithms that can handle that data and can help us understand common processes therein.

A different area where we are trying to advance experimental approaches that feed into AI-based predictions is at the level of how the cell is structured. You know as a cell biologist that location matters, how proteins interact and come together in living cell matters, and that many of the changes in a cell and many of the functions that we care about are not changes in the overall abundance of their parts, but in the interactions of those part. And for a long time, a lot of our broad-based analyses, if we think about RNA-seq, if we think about proteomics, have relied on measuring differences in the abundance of the parts, but not really assembling them into complex pictures.

And there are new methods in proteomics, especially in the field of cross-linking mass spectrometry that allow us to generate spatial constraints for how those parts must come together. We can do this now globally. And in fact, very recently we just obtained the first global data sets for Toxoplasma that gave us a sense of how thousands of different Toxoplasma proteins interact with one another and how the proteins themselves are structured, because you're also obtaining spatial constraints for the individual parasite proteins. This for me is really mind-blowing.

Sally Kornbluth: Presumably, you might be able to use that for drug targeting of the latent infected cells, right? What proteins are interacting on the surface of the parasite? How might you disrupt those interactions, et cetera?

Sebastian Lourido: Yes. The way that this can feed into AI-based structural prediction is really beautiful. I mean, I think many of us have heard about the extraordinary advances in AI-based, and we are really delighted to be collaborating with the Ovchinnikov lab at MIT to use these structural constraints to try to globally predict how the molecular shape of all of these parasite proteins are and how they come together. I think you're absolutely right that as we develop these methods and we're able to take essentially these snapshots of how all of the pieces come together, we want to move towards how are they changing at different states in the acute and the chronic state, but also how is the infected cell changing? What are the interactions that are supporting this remarkable biology? And what's beautiful about that is that we can break to some extent our reliance on genetic manipulation, which has required us to be able to do that in very specific species and is difficult to perform in other organisms.

As long as we can grow it, we can measure all of those molecular details, which I think I'm very excited about being able to apply to other infectious diseases, including many of the infectious diseases that remain as neglected tropical diseases that have received very little attention from pharmaceutical industry and that of course continue to cause millions of infections around the world and which have not benefited from all of the advances in molecular biology that have enriched cancer research, have enriched cardiovascular research, brain research, of course. Can we bring these tools that we almost take for granted here at MIT and the hub of all of this technology? Can we bring them to those neglected tropical diseases?

Sally Kornbluth: Very interesting. So, you're originally from Columbia and you spent a lot of time in your mother's genetics lab. So, what was that like? How did it shape your path into science?

Sebastian Lourido: I don't remember learning what a chromosome was. It was so much a part of our family culture. And I remember as a kid helping my mother cut out chromosomes from the karyotypes that she was assembling for her lab, for cancer research or for diagnosis of congenital disorders. And this was, I think, teaching me that life, which I think is so rich and observable in the natural world, came down to these invisible principles of genetic material being passed from one organism to the other, from parent to child. And so, to me, that was all a little bit second nature. I also grew up spending some time as, of course, she would be meeting with patients or doing her work, playing around with the microscopes in her laboratory, observing both the cells that they were growing, the karyotypes that they were trying to make, and really learning about some of the tools of laboratory science.

Sally Kornbluth: It's such an exciting adventure for a kid, right? You're like, wait, you can do this for a job, just satisfy your curiosity. And it's definitely exciting. So, you double majored in fine art though in cell and molecular biology. So, how do you think about how your art background influences your work, how you think about these problems?

Sebastian Lourido: Growing up in Columbia, I always had those two dueling passions, right? And I think often we see as art and science is two different pulls, but in fact, they're united by creativity. They're united by the desire to discover and create and share those new creations with other individuals. I think that's very central to the motivation of a lot of scientists as it is to a lot of artists. And so, not being able to decide, I decided to come to the US where it was possible to undertake those dual degrees and continue fueling the two flames. And really, as I started as an undergrad at Tulane and over the years that followed, I really fell in love with research as I continued to do a lot of a studio art. And until the very end of my undergrad, I thought, I'm going to try to keep these two alive and see where things go. And it wasn't until I took the next step to go work in Berlin at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology that I really committed to one of those avenues.

Sally Kornbluth: There's such an elegance to biology as well. It's this aesthetic pleasure in biology that I would think you would also get from the fine arts, this sort of beauty.

Sebastian Lourido: Absolutely. And maybe the resonance between different patterns. I think that sometimes when we're overwhelmed by the facts of biology in the introductory classes, it's hard for us to pick up the patterns, but the more you're in it, the more that you learn from colleagues and really embrace the entire field, you start seeing the patterns of life reemerge in very distinct contexts. You start seeing convergence of design, you start seeing the reuse of common elements, and that really does enrich the picture. It gives you a sense of that natural history.

Sally Kornbluth: It's interesting. This is a little bit of an aside, but something you're saying strikes me. We have a lot of discussion about what will education look like in the age of AI. And I always think about how much do you actually have to have in your own head to make those kind of connections you're talking about rather than essentially offloading it to AI, right? That pattern, I mean AI is great at pattern recognition, but for you to see those patterns and have the kind of creative thoughts you're talking about, how do we balance that? It's going to be very interesting.

Sebastian Lourido: I agree. I think about that a lot when teaching cell biology, what is the framework that we have to offer the next generation so that they know what to ask and how to think about the problems? There has been this clear transformation, if I think about the history of cell biology between a field that could be conceivably captured in a single person's mind, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Right.

Sebastian Lourido: If I think about some of my senior colleagues, Harvey Lodish, it really does seem that up to a point he knew all the cell biology that there was to know...

Sally Kornbluth: There was to know. Right, right.

Sebastian Lourido: And over the past 40 years, the amount of knowledge ...

Sally Kornbluth: That's impossible, yeah.

Sebastian Lourido: ... that has accumulated on distinct organisms and pathways, it really is impossible to capture in a single mind. And how do we take that leap to understanding who we should ask, what we should ask, and having a global framework for how things were and operating effectively within that framework. I think that that is one of the challenges. The way that I use some of the large language models that, of course, in All of our lives right now is really thinking about them as expanding the associative memory that is allowing you to say, "Oh yeah, I had not thought about that and I should incorporate that."

Sally Kornbluth: That's right. But then you have something to incorporate it into.

Sebastian Lourido: Correct.

Sally Kornbluth: And that's the question of how you build that mental framework.

Sebastian Lourido: And you need an editor.

Sally Kornbluth: Yeah, exactly. That's right.

Sebastian Lourido: You still need to be your best editor, your most critical editor. And that is the part of our brain that we often shut down when things become easier, right?

Sally Kornbluth: That's right. That's right. Exactly.

Sebastian Lourido: And so, maintaining that high level of self-critique in our work, even as the large language models are making it much easier to produce things that approximate the final product.

Sally Kornbluth: From all of this background, how did you find your way to MIT?

Sebastian Lourido: Yeah. So, after working in Berlin, I decided to return to the US for my PhD, which was at Washington University in St. Louis. That's where I started my work in Toxoplasma in the laboratory of David Sibley, really creative and bold scientists who would always allow us to take risks and bring in new technologies and new ideas into Toxoplasma research. And he was, I think, the one who proposed me looking into some of these fellows programs that allowed newly minted PhDs to start their own laboratory, where typically in our field, we tend to do a postdoc in order to prepare for a faculty position. And so, I applied to a few of these fellows programs. There aren't that many, and I got interviewed at Whitehead.

And so, I joined in 2012, The Whitehead as one of their fellows. And it was just an incredible experience that allowed me to pursue some of those ideas and concentrate in my research for several years. It went really well. We were able to establish some of those first genome-wide screens that I told you about. And I had the great fortune of being recruited thereafter to the biology faculty at MIT. And I really loved both the breadth and the rigor of science at MIT. It just felt like a place where bold ideas could thrive, where you could connect on the basis of curiosity and knowledge and science with other investigators and where their doors were constantly open to a collaboration, insight, advice.

And I've really found that to be true. Even though infectious disease research is a relatively small footprint of what we find at MIT, all of these interactions with other researchers working on RNA biology, working on different chemical biology approaches, collaborators in biological engineering, working on mass spectrometry have really served to enrich our research beyond belief and have allowed us to bring into the field of infectious disease research all sorts of cutting edge approaches. And I don't know that it would've been possible, certainly not to this extent, in another environment.

Sally Kornbluth: This was really brought home to me in the last week in two separate ways. I don't know if you've seen the documentary on Phil Sharp cracking the code.

Sebastian Lourido: I haven't yet.

Sally Kornbluth: So, it's on PBS, you can see it. And it really highlighted this life at MIT as this incubator of incredible science and all of the synergistic interactions between people doing different but related things. The other thing, it was yesterday was the memorial for David Baltimore, the towering Nobel Laureate who had such an impact on MIT and a particular way that...

Sebastian Lourido: And founding director of Whitehead.

Sally Kornbluth: ... Founding Director of Whitehead. But what was funny was David had originally intended that Whitehead Fellows would not be hired as faculty because he didn't want the fellowship to be perceived as an audition. But as they said at the memorial yesterday, he decided that those rules could be superseded because the people were so fantastic that there were a number of the original Whitehead fellows that wound up on the MIT faculty. And you're obviously one of the later ones that wound up on the MIT faculty.

Sebastian Lourido: I received the same prompt when I was hired as a Whitehead fellow.

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, yeah. You weren't going to be hired here.

Sebastian Lourido: No.

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Sebastian Lourido: And certainly I went through the same kind of faculty search process that any other member would've been under.

Sally Kornbluth: That's funny. MIT is a special place and I can understand the opportunity arising and grabbing it.

Sebastian Lourido: Yeah. And trying to, I guess, retain talent and collaborations in different fields.

Sally Kornbluth: Exactly. So, speaking of talent, finally, let me just ask you this. You've been open about being gay, you've been interested in support of the LGBTQ community. From your perspective, what steps could universities in general and MIT in particular perhaps do to really support people from diverse backgrounds? Because we are about getting the very best talent from all quarters, and we want to make sure that everyone's here feels like MIT is their home.

Sebastian Lourido: Absolutely. I think openness and inclusivity are challenging things to implement. And I think that we need to have those conversations that open our eyes to different perspectives in order to be able to recognize differences that otherwise go unnoticed to us because of the limits of our own perspective. And so, for me, it's just been so enriching to be able to listen to some of those personal stories from Dean [Nergis] Mavalvala, from other colleagues throughout MIT. And it is, I think, in sharing that complex process of learning how to belong, of feeling like sometimes we don't belong, that we end up finding, I guess, a common framework for our distinct humanities.

And so, I do think that having opportunities to share that go beyond our professional persona and to listen to each other's stories in an open fashion, I think it's those moments that without knowing it, help other members of our community know that they belong. And so, for me, in my own professional development, I have felt at times vulnerable based on my sexual identity, times based on my immigration status, based on my ethnicity. There are moments where I feel like I don't belong, or maybe I belong for the wrong reasons. I remember when I was hired to the MIT faculty, one of the graduate students, and I wasn't much older than they were, so we were all friends. One of the graduate students at Whitehead, actually someone from Latin America said, "Congratulations. I wanted to be the first diversity hire."

Sally Kornbluth: Oh, wow.

Sebastian Lourido: It was actually the first time that I thought, "Oh wait, is that why they hired me?" And it was such a pernicious thought, right?

Sally Kornbluth: Yes.

Sebastian Lourido: And I mean, I think now I have the confidence in what we have achieved in all of the wonderful research that I've been able to lead by so many talented researchers not to take undue credit that I know that that was a really misdirected statement. But I think that we are all susceptible to those moments where we wonder what role our identity has in the achievements that we've garnered. And I think knowing that others have similarly felt uneasy about their situation and doubted themselves at different times helps us put those experiences in context and recognize that belonging is an ongoing process and that when we feel strong, when we feel powerful, this incumbent on us to open those doors for others to tell those stories and knowing that not everybody feels equally comfortable and equal footing to do that.

Sally Kornbluth: That's right. I mean, when we hire for the very best talent, we're going to have a diverse talent pool. It doesn't mean that they're a diversity hire. We've hired the best talent and people are going to come from a wide range of backgrounds. And the thing that's really struck me, I've now been at MIT for three years. The thing that really strikes me is the people are accepted all kinds of people. You know what I mean? It's just a very interesting, diverse community from maybe people who were very conventional in their viewpoint to very quirky, from very left wing to very right wing. I mean, it's just been incredible because I think the bottom line is everybody here wants to do their best work, and that's the ultimate focus.

Sebastian Lourido: Absolutely. It's, I think, the science and the achievement, but I also think that that process is a human process, right? And so, we actually cannot dissociate those two. And so, how do we create a community where we recognize and accept each other's differences and each other's humanity that also requires a certain proactive approach towards having difficult conversations, having civil and respectful conversations, and in that process of disagreement, not forgetting each other's humanity and all of the things that we actually share.

Sally Kornbluth: That's right. And this is a much longer conversation because this is a problem well beyond MIT, but I'm glad that we got to have some of this conversation today. I learned a lot both about parasites and about you, so it's been great. And to our audience, I want to thank them for listening to Curiosity Unbounded. I very much hope you all will join us again. I'm Sally Kornbluth. Stay curious.

Curiosity Unbounded is a production of MIT News and the Institute Office of Communications, in partnership with the Office of the President. This episode was researched, written, and produced by Christine Daniloff and Melanie Gonick. Our sound engineer is Dave Lishansky. For show notes, transcripts, and other episodes, please visit news.mit.edu/podcasts/curiosity-unbounded. Please find us on YouTube, Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. To learn about the latest developments and updates from MIT, please visit news.mit.edu. You can follow us on Facebook and Instagram at CuriosityUnboundedPodcast.

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you’ll tune in next time when Sally will be speaking with Emil Verner, an associate professor of management and financial economics at MIT. In this conversation, Emil takes us through 150 years of history to explain why financial crises keep happening, how they impact ordinary people — not just markets — and what lessons we can learn to build a more stable future.

Glossary:

Toxoplasmosis is an infection caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. It’s a common parasitic infection that many people carry without knowing it, because it often causes no symptoms in healthy individuals.

People can become infected by:

- Eating undercooked or raw meat containing the parasite

- Handling cat litter or soil contaminated with infected cat feces

- Consuming contaminated food or water

- Passing the infection from mother to fetus during pregnancy

Health effects:

- Most healthy people: no symptoms or mild, flu-like illness

- Pregnant people: risk of serious complications for the fetus

- Immunocompromised individuals: can cause severe illness affecting the brain, eyes, or other organs

Lysis: In biology, lysis refers to the breakdown of a cell caused by damage to its plasma (outer) membrane. It can be caused by chemical or physical means (for example, strong detergents or high-energy sound waves) or by a viral infection.

Parasitism: Parasitism is a type of relationship between two living organisms in which one benefits while the other is harmed.

AP complex: AP complex (short for Adaptor Protein complex) is a group of proteins that acts like a shipping and sorting system inside cells. Put simply, AP complexes help cells move the right molecules to the right place at the right time.

Phenotype: Phenotype refers to the observable characteristics of a living organism — what it looks like and how it behaves.

Proteomics: Proteomics is the study of all the proteins in a cell, tissue, or organism and how they work together.