MIT technology has once again driven the quest for speed on the water in the ancient art of sailing. As the America's Cup defenders race goes down to the wire Tuesday, two out of three of the American syndicates vying for the honor of defending the America's Cup have boats designed by professors from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ocean Engineering Department.

The America's Cup defenders today are in a three-way win-or-die battle, with the Mighty Mary of America3 and Stars & Stripes/Dennis Conner scheduled to race this afternoon. If Mighty Mary wins, it will face off against Young America/PACT 95 and Stars & Stripes will be out of the competition. If Stars & Stripes wins, it will be the defender and will then take on the challenger, New Zealand, for the Cup.

Professors Paul Sclavounos and Jerry Milgram have different ideas about what combinations will yield the fastest boat under all conditions. Professor Sclavounos, the principal scientist for the Young America/PACT 95 design team, proudly describes the innovative winged rudder on Young America as the innovation of this America's Cup. "The data out of our computer tells us it will really increase boat speed," he said.

Professor Jerry Milgram, design director of Mighty Mary/America 3 , has a radical "whale's tail" design for the keel, the bulbous stabilizing element attached to the bottom of a racing yacht's hull, and a very long, 13-foot rudder. While Milgram agrees that rudder wings show enough promise to be worthy of a full-scale experiment, the evaluations and tests by A3 indicated that gain or loss was small either way.

The two boats have set different priorities. A3 has concentrated on improving light air capabilities after being the clear winner in heavy conditions in 1992. (Sclavounos, now with PACT 95, was responsible for the research on rough seas that aided the A3 effort in 1992.) PACT 95 , on the other hand, has concentrated on performing well in rough water.

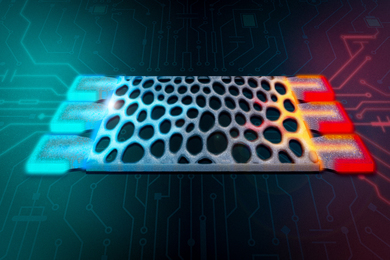

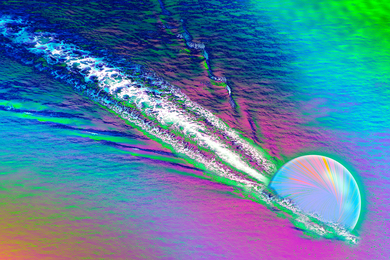

Sclavounos and his cadre at MIT are also responsible for a computer program called Ship Wave Analysis (SWAN), which allows measurement of the water flow around a ship's hull. Being able to measure the performance of a boat in waves allowed them to test hundreds of hull designs by computer simulation. He says 1% difference in speed translates to 1 minute on the race course.

Two weeks ago, the veil of secrecy around the ships' designs was dropped and the America's Cup contenders showed their keels, which are also known as bulbs. This was done to alleviate the intelligence and counterintelligence subterfuge that had grown as technology assumed greater importance. The results surprised many.

New Zealand, which has been steamrollering the foreign competition (the Challengers) and was thought to have some new secret appendage, has a rather conventional design, including its bulb.

According to Sclavounos, it shares the "minimalist" approach with PACT 95's Young America. The most visible design difference is that New Zealand has large "unswept" winglets extending straight out from the bulb, whereas Young America has "swept" winglets angled toward the stern of the boat to allow kelp to slide away.

A3 and Australia were described as more "maximalist" by Sclavounos. Milgram agreed that they are a little more exotic, but only because of their appendages. A3 has a very long rudder-at 13 feet it was the maximum allowed. Initially, it also had the first ever all-women's team, which has now been joined by Dave Dellenbaugh, as tactician. The women, while top-notch athletes and dinghy (small boat) racers, have not had experience in big boat racing, which offers different challenges.

"With a less experienced sailing team, we as designers needed to accommodate to that," said Milgram. "We designed a deeper rudder to be efficient at the unusually large rudder angles these particular sailors seemed to need to steer well. Mighty Mary, with its sleek narrow hull and relatively small keel has terrific maneuvering but keeping it aimed correctly is a challenge.

"We have a radical bulb (keel), " said Milgram. "It's short, shaped like a whale's tail. It has the best faring of winglets to keel, we think. Whales do their tails very nicely, they've had so long to evolve."

Since two designers formerly with A3 went to Australia this time, it is not surprising that the boats would more closely resemble each other. The Australian team is headed by John Bertrand, who won the America's Cup in 1983 and is a student of Milgram's and a 1972 graduate of MIT. "We've been thinking we should charge Australia a copyright fee", Milgram joked. He was quick to add, at the memory of the disastrous sinking of Australia's new boat, "but we're a lot stronger. Remember, New Zealand and A3 are the only ones of the boats remaining which haven't nearly sunk ." Pushing the envelope of design for speed has made many boats more fragile than in the past.

The third syndicate, that of Dennis Conner, has relatively little technology in its program. Its bulb has an unusual dip in the middle, which is difficult to see from the photo angles that were permitted at the unveiling. It is the slowest boat by all reports, yet continues to surprise with wins and brilliant tactical sailing.

So, how much of the art is intuitive and emotional, and how much is technology? Both are needed these days, say the experts.

Professor Milgram says, "A difficult challenge is getting the fruits of the science put into practice. The sailors need to learn to coordinate their intuition with the technical findings, and the scientists and engineers need to learn to make the boat perform optimally when the sailors are using their intuition."

For example, he said, the sailors like the feel of the boat at excessive heel angles. Heeling is when the boat leans far over to one side, bringing the center of gravity higher and thereby slowing the boat speed. The designers are then pressed to distribute the weight in the boat for less than the optimum heel stability. This robs the sails of power, and the sails are the engine. It takes time in the office and on the water to bring all elements together to the point where the crew is comfortable sailing a boat going as fast as it can, he said.

The entire effort, says Milgram, is a massive system project involving management, fund-raising, science, technology, and, most-importantly, the skills of the team on the water. Although science and technology can improve the overall result, it adds to the overall time required to do the project. If the managers of the projects started sooner, it would greatly increase their chances of success, he says.

Professor Milgram thinks that good sail shapes, good sail control and good sailing will decide the winner. Since most of the boats' hulls are similar to the A3 Cup-winner of 1992, Milgram thinks that boat design will be less of a factor this time. Professor Sclavounos, with a grin, says, "We'll see."