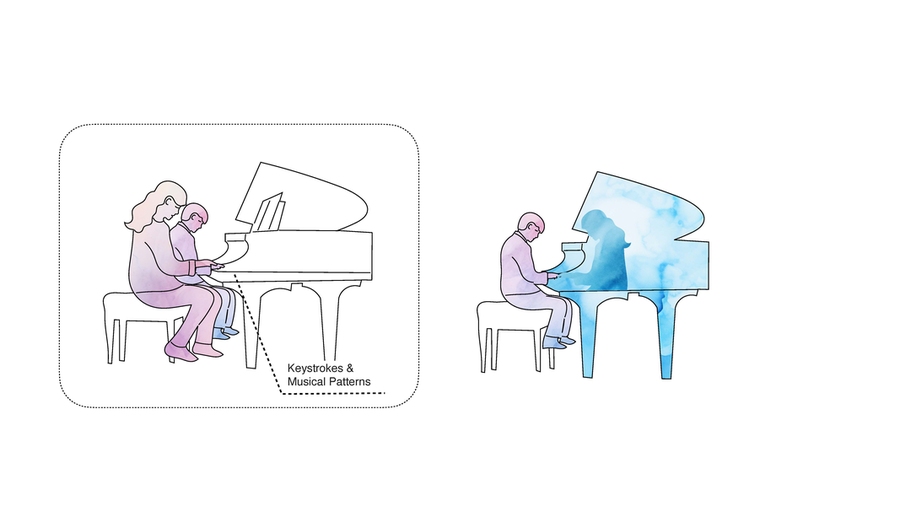

In the dim light of the lab, friends, family, and strangers watched the image of a pianist playing for them, the pianist’s fingers projected onto the moving keys of a real grand piano that filled the space with music.

Watching the ghostly musicians, faces and bodies blurred at their edges, several listeners shared one strong but strange conviction: “feeling someone’s presence” while “also knowing that I am the only one in the room.”

“It’s tough to explain,” another listener said. “It felt like they were in the room with me, but at the same time, not.”

That presence of absence is at the heart of TeleAbsence, a project by the MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media group that focuses on technologies that create illusory communication with the dead and with past selves.

But rather than a “Black Mirror”-type scenario of synthesizing literal loved ones, the project led by Hiroshi Ishii, the Jerome B. Wiesner Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, instead seeks what it calls “poetic encounters” that reach across time and memory.

The project recently published a positioning paper in PRESENCE: Virtual and Augmented Reality that presents the design principles behind TeleAbsence, and how it could help people cope with loss and plan for how they might be remembered.

The phantom pianists of the MirrorFugue project, created by Tangible Media graduate Xiao Xiao ’09, SM ’11, PhD ’16, are one of the best-known examples of the project. On April 30, Xiao, now director and principal investigator at the Institute for Future Technologies of Da Vinci Higher Education in Paris, shared results from the first experimental study of TeleAbsence through MirrorFugue at the 2025 CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Yokohama, Japan.

When Ishii spoke about TeleAbsence at the XPANSE 2024 conference in Abu Dhabi, “about 20 people came up to me after, and all of them told me they had tears in their eyes … the talk reminded them about a wife or a father who passed away,” he says. “One thing is clear: They want to see them again and talk to them again, metaphorically.”

Messages in bottles

As the director of the Tangible Media group, Ishii has been a world leader in telepresence, using technologies to connect people over physical distance. But when his mother died in 1998, Ishii says the pain of the loss prompted him to think about how much we long to connect across the distance of time.

His mother wrote poetry, and one of his first experiments in TeleAbsence was the creation of a Twitterbot that would post snippets of her poetry. Others watching the account online were so moved that they began posting photos of flowers to the feed to honor the mother and son.

“That was a turning point for TeleAbsence, and I wanted to expand this concept,” Ishii says.

Illusory communication, like the posted poems, is one key design principle of TeleAbsence. Even though users know the “conversation” is one-way, the researchers write, it can be comforting and cathartic to have a tangible way to reach out across time.

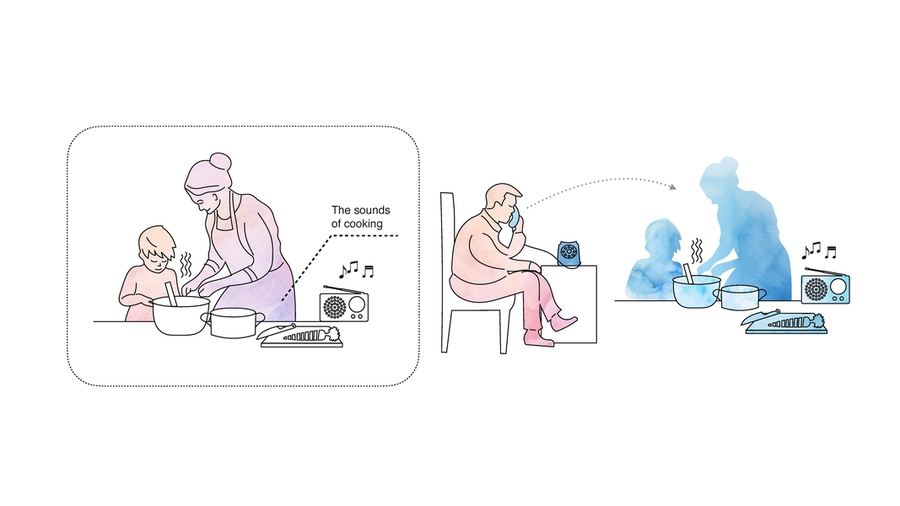

Finding ways to make memories material is another important design principle. One of the projects created by Ishii and colleagues is a series of glass bottles, reminiscent of the soy sauce bottles Ishii’s mother used while cooking. Open one of the bottles, and the sounds of chopping, of sizzling onions, of a radio playing quietly in the background, of a maternal voice, reunite a son with his mother.

Ishii says sight and sound are the primary modalities of TeleAbsence technologies for now, because although the senses of touch, smell, and taste are known to be powerful memory triggers, “it is a very big challenge to record that kind of multimodal moment.”

At the same time, one of the other pillars of TeleAbsence is the presence of absence. These are the physical markers, or traces, of a person that serve to remind us both of the person and that the person is gone. One of the most powerful examples, the researchers write, is the permanent “shadow” of Hiroshima Japanese resident Mitsuno Ochi, her silhouette transferred to stone steps 260 meters from where the atomic bomb detonated in 1945.

“Abstraction is very important,” Ishii says. “We want something to recall a moment, not physically recreate it.”

With the bottles, for instance, people have asked Ishii and his colleagues whether it might be more evocative to fill them with a perfume or drink. “But our philosophy is to make a bottle completely empty,” he explains. “The most important thing to let people imagine, based on the memory.”

Other important design principles within TeleAbsence include traces of reflection — the ephemera of faint pen scratches and blotted ink on a preserved letter, for instance — and the concept of remote time. TeleAbsence should go beyond dredging up a memory of a loved one, the researchers insist, and should instead produce a sense of being transported to spend a moment in the past with them.

Time travelers

For Xiao, who has played the piano her whole life, MirrorFugue is a “deeply personal project” that allowed her to travel to a time in her childhood that was almost lost to her.

Her parents moved from China to the United States when she was a baby — but it took eight years for Xiao to follow. “The piano, in a sense, was almost like my first language,” she recalls. “And then when I moved to America, my brain overwrote bits of my childhood where my operating system used to be in Chinese, and now it’s very much in English. But throughout this whole time, music and the piano stayed constant.”

MirrorFugue’s “sense of kind-of being there and not being there, and the wish to connect with oneself from the past, comes from my own desire to connect with my own past self,” she adds.

The new MirrorFugue study puts some empirical data behind the concept of TeleAbsence, she says. Its 28 participants were fitted with sensors to measure changes in their heart rate and hand movements during the experience. They were extensively interviewed about their perceptions and emotions afterward. The recorded images came from pianists ranging in experience from children early in their lessons to professional pianists like the late Ryuichi Sakamoto.

The researchers found that emotional experiences described by the listeners were significantly influenced by whether the listeners knew the pianist, as well as whether the pianist was known by the listeners to be alive or dead.

Some participants placed their own hands alongside the ghosts to play impromptu duets. One daughter, who said she had not paid close attention to her father’s playing when he was alive, was newly impressed by his talent. One person felt empathy watching his past self struggle through a new piece of music. A young girl, mouth slightly open in concentration and fingers small on the keys, showed her mother a past daughter that wasn’t possible to see in old photos.

The longing for past people and past selves can be “a deep sadness that will never go away,” says Xiao. “You’ll always carry it with you, but it also makes you sensitive to certain aesthetic experiences that’s also beautiful.”

“Once you’ve had that experience, it really resonates,” she adds, “And I think that’s why TeleAbsence resonates with so many people.”

Uncanny valleys and curated memory

Acutely aware of the potential ethical dangers of their research, the TeleAbsence scientists have worked with grief researchers and psychologists to better understand the implications of building these bridges through time.

For instance, “one thing we learned is that it depends on how long ago a person passed away,” says Ishii. “Right after death, when it’s very difficult for many people, this representation matters. But you have to make important informed decisions about whether this drags out the grief too long.”

TeleAbsence could comfort the dying, he says, by “knowing there is a means by which they are going to live on for their descendants.” He encourages people to consider curating “high-quality, condensed information,” such as their social media posts, that could be used for this purpose.

“But of course many families do not have ideal relationships, so I can easily think of the case where a descendant might not have any interest” in interacting with their ancestors through TeleAbsence, Ishii notes.

TeleAbsence should never fully recreate or generate new content for a loved one, he insists, pointing to the rise of “ghost bot” startups, companies that collect data on a person to create an “artificial, generative AI-based avatar that speaks what they never spoke, or do gestures or facial expressions.”

A recent viral video of a mother in Korea “reunited” in virtual reality with an avatar of her dead daughter, Ishii says, made him “very depressed, because they’re doing grief as entertainment, consumption for an audience.”

Xiao thinks there might still be some role for generative AI in the TeleAbsence space. She is writing a research proposal for MirrorFugue that would include representations of past pianists. “I think right now we’re getting to the point with generative AI that we can generate hand movements and we can transcribe the MIDI from the audio so that we can conjure up Franz Listz or Mozart or somebody, a really historical figure.”

“Now of course, it gets a little bit tricky, and we have discussed this, the role of AI and how to avoid the uncanny valley, how to avoid deceiving people,” she says. “But from a researcher’s perspective, it actually excites me a lot, the possibility to be able to empirically test these things.”

The importance of emptiness

Along with Ishii’s mother, the PRESENCE paper was also dedicated “in loving memory” to Elise O’Hara, a beloved Media Lab administrative assistant who worked with Tangible Media until her unexpected death in 2023. Her presence — and her absence — are felt deeply every day, says Ishii.

He wonders if TeleAbsence could someday become a common word “to describe something that was there, but is now gone.”

“When there is a place on a bookshelf where a book should be,” he says, “my students say, ‘oh, that’s a teleabsence.’”

Like a sudden silence in the middle of a song, or the empty white space of a painting, emptiness can hold important meaning. It’s an idea that we should make more room for in our lives, Ishii says.

“Because now we’re so busy, so many notification messages from your smartphone, and we are all distracted, always,” he suggests. “So emptiness and impermanence, presence of absence, if those concepts can be accepted, then people can think a bit more poetically.”