Prototyping large structures with integrated electronics, like a chair that can monitor someone’s sitting posture, is typically a laborious and wasteful process.

One might need to fabricate multiple versions of the chair structure via 3D printing and laser cutting, generating a great deal of waste, before assembling the frame, grafting sensors and other fragile electronics onto it, and then wiring it up to create a working device.

If the prototype fails, the maker will likely have no choice but to discard it and go back to the drawing board.

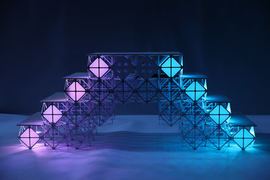

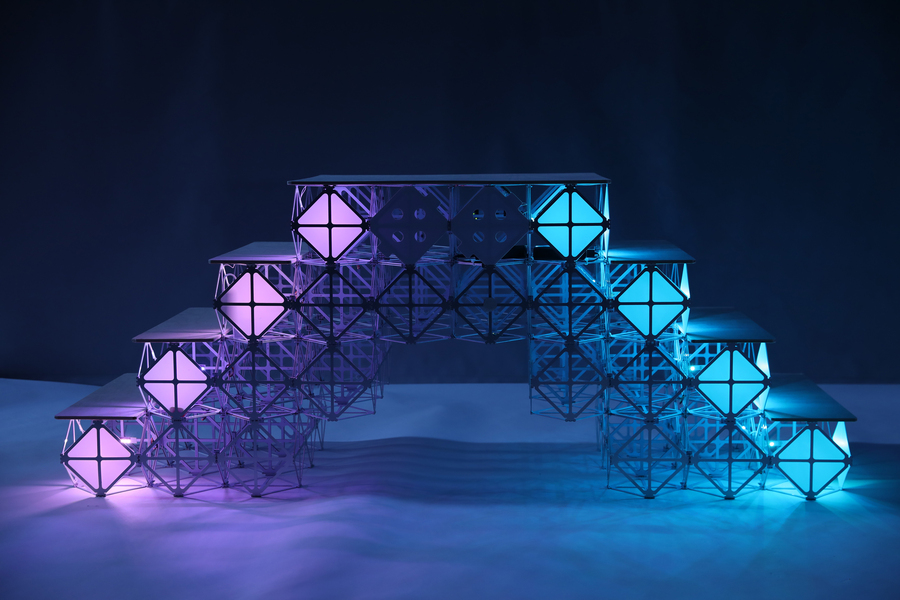

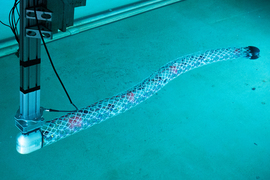

MIT researchers have come up with a better way to iteratively design large and sturdy interactive structures. They developed a rapid development platform that utilizes reconfigurable building blocks with integrated electronics that can be assembled into complex, functional devices. Rather than building electronics into a structure, the electronics become the structure.

These lightweight three-dimensional lattice building blocks, known as voxels, have high strength and stiffness, along with integrated sensing, response, and processing abilities that enable users without mechanical or electrical engineering expertise to rapidly produce interactive electronic devices.

The voxels, which can be assembled, disassembled, and reconfigured almost infinitely into various forms, cost about 50 cents each.

The prototyping platform, called VIK (Voxel Invention Kit), includes a user-friendly design tool that enables end-to-end prototyping, allowing a user to simulate the structure’s response to mechanical loads and iterate on the design as needed.

“This is about democratizing access to functional interactive devices. With VIK, there is no 3D printing or laser cutting required. If you just have the voxel faces, you are able to produce these interactive structures anywhere you want,” says Jack Forman, an MIT graduate student in media arts and sciences and affiliate of the MIT Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA) and the MIT Media Lab, and co-lead author of a paper on VIK.

Forman is joined on the paper by co-lead author and fellow graduate student Miana Smith; graduate student Amira Abdel-Rahman; and senior author Neil Gershenfeld, an MIT professor and director of the CBA. The research will be presented at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Functional building blocks

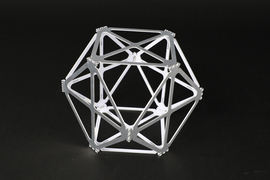

VIK builds upon years of work in the CBA to develop discrete, cellular building blocks called voxels. One voxel, an aluminum cuboctahedra lattice (which has eight triangular faces and six square faces), is strong enough to support 228 kilograms, or about the weight of an upright piano.

Instead of being 3D printed, milled, or laser cut, voxels are assembled into largescale, strong, durable structures like airplane components or wind turbines that can respond to their environments.

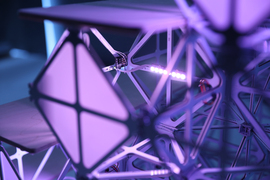

The CBA team merged voxels other work in their lab centered on interconnected electrical components, yielding voxels with structural electronics. Assembling these functional voxels generates structures that can transmit data and power, as well as mechanical forces, without the need for wires.

They used these electromechanical building blocks to develop VIK.

“It was an interesting challenge to think about adapting a lot of our previous work, which has been about hitting hard engineering metrics, into a user-friendly system that makes sense and is fun and easy for people to work with,” Smith says.

For instance, they made the voxel design larger so the lattice structures are easier for human hands to assemble and disassemble. They also added aluminum cross-bracing to the units to improve their strength and stability.

In addition, VIK voxels have a reversible, snap-fit connection so a user can seamlessly assemble them without the need for additional tools, in contrast to some prior voxel designs that used rivets as fasteners.

“We designed the voxel faces to permit only the correct connections. That means that, if you are building with voxels, you are guaranteed to be building the correct wiring harness. Once you finish your device, you can just plug it in and it will work,” says Smith.

Wiring harnesses can add significant cost to functional systems and can often be a source of failure.

An accessible prototyping platform

To help users who have minimal engineering expertise create a wide array of interactive devices, the team developed a user-friendly interface to simulate 3D voxel structures.

The interface includes a Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulation model that enables users to draw out a structure and simulate the forces and mechanical loads that will be applied to it. It adds colors to an animation of the user’s device to identify potential points of failure.

“We created what is essentially a ‘Minecraft’ for voxel applications. You don’t need a good sense of civil engineering or truss analysis to verify that the structure you are making is safe. Anyone can build something with VIK and have confidence in it,” Forman says.

Users can also easily integrate off-the-shelf modules, like speakers, sensors, or actuators, into their device. VIK emphasizes flexibility, enabling makers to use the types of microcontrollers they are comfortable with.

“The next evolution of electronics will be in three-dimensional space and the Voxel Invention Kit (VIK) is the stepping stone that will enable users, designers, and innovators a way to visualize and integrate electronics directly into structures,” says Victor Zaderej, manager of advanced electronics packaging technology at Molex, a manufacturer of electronic, electrical, and fiber optic connectivity systems. “Think of the VIK as the merging of a Lego building kit and an electronics breadboard. When creative engineers and designers begin thinking about potential applications, the opportunities and unique products that will be enabled will be limitless.”

Using the design tool for feedback, a maker can rapidly change the configuration of voxels to adjust a prototype or disassemble the structure to build something new. If the user eventually wishes to discard the device, the aluminum voxels are fully recyclable.

This reconfigurability and recyclability, along with the high strength, high stiffness, light weight, and integrated electronics of the voxels, could make VIK especially well-suited for applications such as theatrical stage design, where stage managers want to support actors safely with customizable set pieces that might only exist for a few days.

And by enabling the rapid-prototyping of large, complex structures, VIK could also have future applications in areas like space fabrication or in the development of smart buildings and intelligent infrastructure for sustainable cities.

But for the researchers, perhaps the most important next step will be to get VIK out into the world to see what users come up with.

“These voxels are now so readily available that someone can use them in their day-to-day life. It will be exciting to see what they can do and create with VIK,” adds Forman.