Imagine that the head of a company office is misbehaving, and a disillusioned employee reports the problem to their manager. Instead of the complaint getting traction, however, the manager sidesteps the issue and implies that raising it further could land the unhappy employee in trouble — but doesn’t deny that the problem exists.

This hypothetical scenario involves an open secret: a piece of information that is widely known but never acknowledged as such. Open secrets often create practical quandaries for people, as well as backlash against those who try to address the things that the secrets protect.

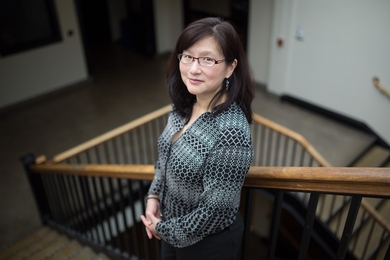

In a newly published paper, MIT philosopher Sam Berstler contends that open secrets are pervasive and problematic enough to be worthy of systematic study — and provides a detailed analysis of the distinctive social dynamics accompanying them. In many cases, she proposes, ignoring some things is fine — but open secrets present a special problem.

After all, people might maintain friendships better by not disclosing their salaries to each other, and relatives might get along better if they avoid talking politics at the holidays. But these are just run-of-the-mill individual decisions.

By contrast, open secrets are especially damaging, Berstler believes, because of their “iterative” structure. We do not talk about open secrets; we do not talk about the fact that we do not talk about them; and so on, until the possibility of addressing the problems at hand disappears.

“Sometimes not acknowledging things can be very productive,” Berstler says. “It’s good we don’t talk about everything in the workplace. What’s different about open secrecy is not the content of what we’re not acknowledging, but the pernicious iterative structure of our practice of not acknowledging it. And because of that structure, open secrecy tends to be hard to change.”

Or, as she writes in the paper, “Open secrecy norms are often moral disasters.”

Beyond that, Berstler says, the example of open secrets should enable us to examine the nature of conversation itself in more multidimensional terms; we need to think about the things left unsaid in conversation, too.

Berstler’s paper, “The Structure of Open Secrets,” appears in advance online form in Philosophical Review. Berstler, an assistant professor and the Laurance S. Rockefeller Career Development Chair in MIT’s Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, is the sole author.

Eroding our knowledge

The concept of open secrets is hardly new, but it has not been subject to extensive philosophical rigor. The German sociologist Georg Simmel wrote about them in the early 20th century, but mostly in the context of secret societies keeping quirky rituals to themselves. Other prominent thinkers have addressed open secrets in psychological terms. To Berstler, the social dynamics of open secrets merit a more thorough reckoning.

“It’s not a psychological problem that people are having,” she says. “It’s a particular practice that they’re all conforming to. But it’s hard to see this because it’s the kind of practice that members, just in virtue of conforming to the practice, can’t talk about.”

In Berstler’s view, the iterative nature of open secrets distinguishes them. The employee expecting a candid reply from their manager may feel bewildered about the lack of a transparent response, and that nonacknowledgement means there is not much recourse to be had, either. Eventually, keeping open secrets means the original issue itself can be lost from view.

“Open secrets norms are set up to try to erode our knowledge,” Berstler says.

In practical terms, people may avoid addressing open secrets head-on because they face a familiar quandary: Being a whistleblower can cost people their jobs and more. But Berstler suggests in the paper that keeping open secrets helps people define their in-group status, too.

“It’s also the basis for group identity,” she says.

Berstler avoids taking the position that greater transparency is automatically a beneficial thing. The paper identifies at least one kind of special case where keeping open secrets might be good. Suppose, for instance, a co-worker has an eccentric but harmless habit their colleagues find out about: It might be gracious to spare them simple embarrassment.

That aside, as Berstler writes, open secrets “can serve as shields for powerful people guilty of serious, even criminal wrongdoing. The norms can compound the harm that befalls their victims … [who] find they don’t just have to contend with the perpetrator’s financial resources, political might, and interpersonal capital. They must go up against an entire social arrangement.” As a result, the chances of fixing social or organizational dysfunction diminish.

Two layers of conversation

Berstler is not only trying to chart the dynamics and problems of open secrets. She is also trying to usefully complicate our ideas about the nature of conversations and communication.

Broadly, some philosophers have theorized about conversations and communication by focusing largely on the information being shared among people. To Berstler, this is not quite sufficient; the example of open secrets alerts us that communication is not just an act of making things more and more transparent.

“What I’m arguing in the paper is that this is too simplistic a way to think about it, because actual conversations in the real world have a theatrical or dramatic structure,” Berstler says. “There are things that cannot be made explicit without ruining the performance.”

At an office holiday party, for instance, the company CEO might maintain an illusion of being on equal footing with the rest of the employees if the conversation is restricted to movies and television shows. If the subject turns to year-end bonuses, that illusion vanishes. Or two friends at a party, trapped in an unwanted conversation with a third person, might maneuver themselves away with knowing comments, but without explicitly saying they are trying to end the chat.

Here Berstler draws upon the work of sociologist Erving Goffman — who closely studied the performative aspects of everyday behavior — to outline how a more multi-dimensional conception of social interaction applies to open secrets. Berstler suggests open secrets involve what she calls “activity layering,” which in this case suggests that people in a conversation involving open secrets have multiple common grounds for understanding, but some remain unspoken.

Further expanding on Goffman’s work, Berstler also details how people may be “mutually collaborating on a pretense,” as she writes, to keep an open secret going.

“Goffman has not really systematically been brought into the philosophy of language, so I am showing how his ideas illuminate and complicate philosophical views,” Berstler says.

Combined, a close analysis of open secrets and a re-evaluation of the performative components of conversation can help us become more cognizant about communication. What is being said matters; what is left unsaid matters alongside it.

“There are structural features of open secrets that are worrisome,” Berstler says. “And because of that we have to more aware [of how they work].”