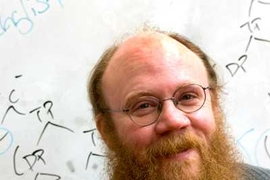

Back in the spring of 2022, professor of linguistics David Pesetsky was talking to an undergraduate class about relative clauses, which add information to sentences. For instance: “The senator, with whom we were speaking, is a policy expert.” Relative clauses often feature “who,” “which,” “that,” and so on.

Before long a student, Kanoe Evile ’23, raised her hand.

“How does this account for the ‘whom of which’ construction?” Evile asked.

Pesetsky, who has been teaching linguistics at MIT since 1988, had never encountered the phrase “whom of which” before.

“I thought, ‘What?’” Pesetsky recalls.

But to Evile, “whom of which” seems normal, as in, “Our striker, whom of which is our best player, scores a lot of goals.” After the class she talked to Pesetsky. He suggested Evile write a paper about it for the course, 24.902 (Introduction to Syntax).

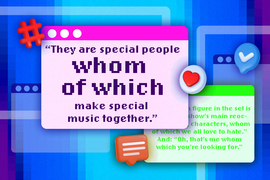

“He said, ‘I’ve never heard of that, but it might make an interesting topic,’” Evile says. She started hunting for online examples that evening. Some of the material she ultimately found came from social media; one example was in a Connecticut state government document. Among her finds: “Dave, Carter, Stefan, LeRoi, Boyd, and Tim are special people whom of which make special music together.”

And: “Our 7th figure in the set is one of the show’s main reoccurring [sic] characters, whom of which we all love to hate.”

And: “Oh, that’s me whom which you’re looking for.” (Sometimes “of” is dropped.)

Evile, a biological engineering major, wrote the paper and went back to studying cells. But Pesetsky, after querying colleagues and others, found that “whom of which” was a largely overlooked phenomenon; virtually no scholars had heard of it. He thought the subject merited further scrutiny. In early 2023, he and Evile set up an independent study project: How does “whom of which” work?

As Evile and Pesetsky show in a newly published paper, “whom of which” obeys very specific rules, whose nature contributes to a larger discussion about sentence construction. The paper, “Wh-which relatives and the existence of pied piping,” appears this month in the journal Glossa.

“It seems to be brand new, and it’s very colloquial, but it’s extremely law-governed,” says Pesetsky, the Ferrari P. Ward Professor of Modern Languages and Linguistics at MIT.

Diversity and unity

When Evile and Pesetsky formally analyzed their “whom of which” examples, they found that, pertaining to its semantics, people consistently use “whom of which” the same way they use “whom.” The expression is not random gibberish.

“With things like this, people are not being silly or uneducated,” Pesetsky says.

Evile and Pesetsky then dug into syntax matters. As many MIT linguists emphasize, human language is both diversified and unified. Languages seem wildly different from each other, but scholars have identified many universal features. These often involve syntax, the organization of sentences.

On this front, “whom of which” relates to “wh-movement,” the way certain sentences are reordered. Suppose we say, “Anna bought something.” To turn that into a question with wh-words, we might say, “What did Anna buy?” In the process, wh-words are placed to the left, and others get reshuffled.

But sometimes multiple words move left, a phenomenon the linguist John Roberts Ross PhD ’67 identified and called “pied piping” in his MIT dissertation. In the question, “Which kind of wine did Anna buy?” not only the wh-word, “which,” but also “kind of wine” moved to the front of the sentence — the wh-word acting like the pied piper of legend, with other words following it.

“The question has always been, why does pied piping exist?” Pesetsky says. “If the left edge of a question or relative clause wants to have a wh-word in it, why doesn’t it just take the wh-word? Why does it take a bunch of other words along with it?”

This is partly why Pesetsky was excited to examine the “whom of which” issue: It provides a new multiword construction for studying wh-movement. What Evile and Pesetsky found, though, was unexpected.

Pied piper chat

In the first place, Evile and Pesetsky found that “whom of which” may provide evidence for a controversial theory about the pied piping phenomenon, developed by linguist Seth Cable PhD ’07. What is puzzling about pied piping is its randomness, the wh-word pulling other words along with it for no apparent reason. Cable noticed that in the Alaskan language Tlingit, questions that look like they feature pied piping always have a particle, “sá,” following the moved words. In the sentence “Aadóo yaagú sá ysiteen?” — “Whose boat did you see?” — what looks like pied piping is just the normal reordering of “sá” plus the words that depend on it. To linguists, what is moving is not random, but the phrase “headed” by the particle.

Evile and Pesetsky think “of” has much of the same function as “sá” in the “whom of which” sentences.

“Our idea is that the ‘of’ is really this sá-like element,” Pesetsky says. “The ‘of’ is really the head of the relativizing phrase, just as Tlingit “sá” is the head of the question phrase.”

Normally, linguists would expect that word to appear on the far left-hand side of the relative clause because that is where heads of phrases appear in English. (Tlingit is the opposite.) But in “whom of which” sentences, “of” is not on the far left. “Whom” is. However, as the paper notes, a similar puzzle occurs in the Mayan language Ch’ol, for which the linguist Jessica Coon PhD ’10 has provided a solution that Evile and Pesetsky easily adapted to the “whom of which” construction.

“In ‘whom of which,’ the whom moves to the left of a relative marker,” Pesetsky notes.

But that is not the end of the story. The “whom of which” construction also appears to tolerate quite complex examples with “recursive” instances of movement not predicted by the proposals of Cable and Coon. Here, however, Evile and Pesetsky find a parallel in the way pied piping works in Finnish, and conjecturally advance a unified proposal for all these languages together.

So, it remains a somewhat open question how much the “whom of which” evidence undercuts or supports pied piping. And another, seemingly less technical question lingers on. As Evile and Pesetsky note in the paper, “the surprising preference for whom over who remains unexplained.”

Why say it?

Whatever the best interpretation is, the whole issue reinforces how syntax systems shape language.

“All this stuff is law-governed,” Pesetsky says. “Websites say, ‘You shouldn’t talk like this.’ That could be a stylistic decision. People who are condemning ‘whom of which’ call it wordy, and if you’re an editor, maybe you want to red-pencil it for that reason. But it’s never sloppy or non-lawlike. It’s always following, when you poke at it, rules of its own.”

Still, in everyday life, why do people say “whom of which,” and not just “who” or “whom”?

“My first explanation was, it felt more formal to me,” Evile says. “Also, if I’m trying to explain something slowly, by taking the extra time to use the phrase, it helps people process it a bit easier. But it’s interesting that we’ve found opposite cases, where people use it casually.”

Evile and Pesetsky think “whom of which” use may be a generational thing. But it is not, as online searches show, a regional phenomenon. “It’s spontaneously popping up around the world,” Evile says. “I’m from Hawai’i and people I know in Hawai’i use it, but my only friend at MIT who would accept the phrase was from Chicago.”

Evile, now a medical student at Columbia University, says studying the issue helped broaden her intellectual horizons.

“It pushed me to do my minor in linguistics,” Evile says. “This was a really fun experience. I am grateful to David and the linguistics department. It’s good to have this scientific mindset, but instead of only applying it in the lab, applying it to language.”

Pesetsky also posted a draft of the paper online for other linguists, some of whom of which quickly responded.

“Innovative nonstandard forms with ‘whom,’ what a time to be alive,” quipped New York University linguist Gary Thoms.

That amused Pesetsky, for whom which the paper’s unresolved issues remain a subject of keen curiosity.

“We discovered some interesting things,” Pesetsky says. “There are also some important questions we end up without answers to. But we’ve launched a discussion.”