Data, and more specifically using data, is not a new concept, but it remains an elusive one. It comes with terms like “the internet of things” (IoT) and “the cloud,” and no matter how often those are explained, smart people can still be confused. And then there’s the amount of information available and the speed with which it comes in. Software is omnipresent. It’s in coffeemakers and watches, gathering data every second. The question becomes how to take all the new technology and take advantage of the potential insights and analytics. It’s not a small ask.

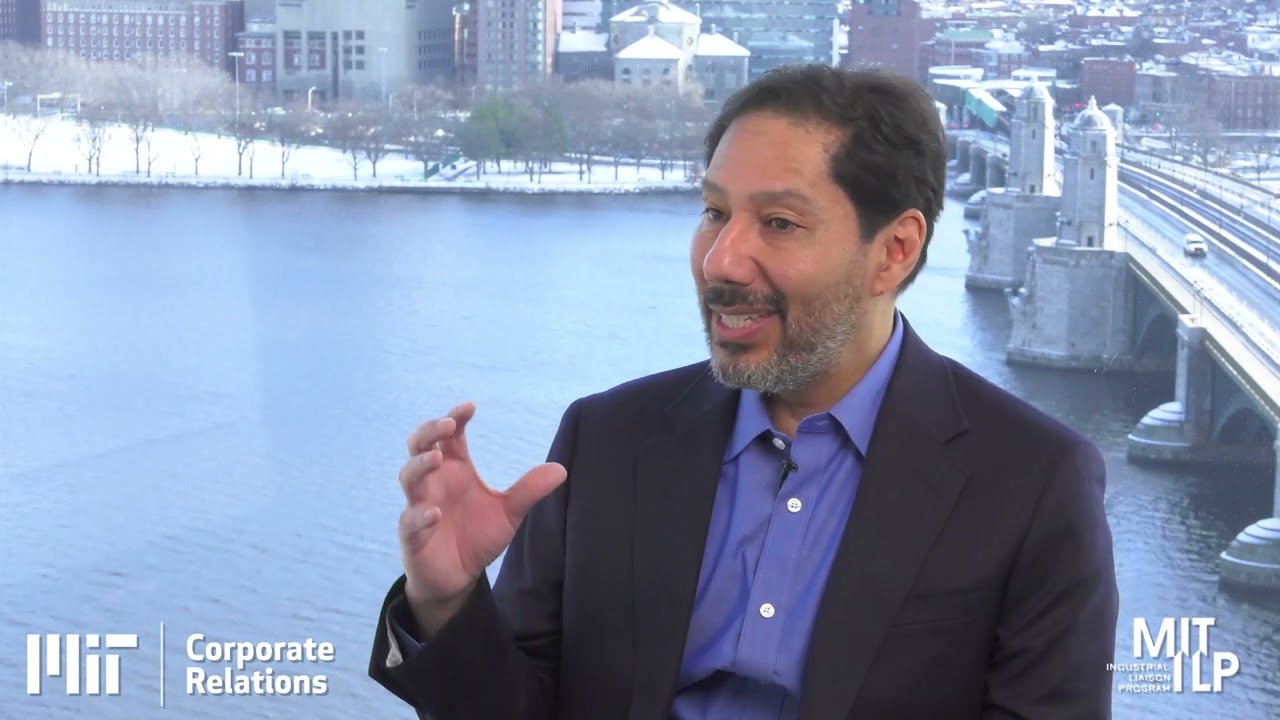

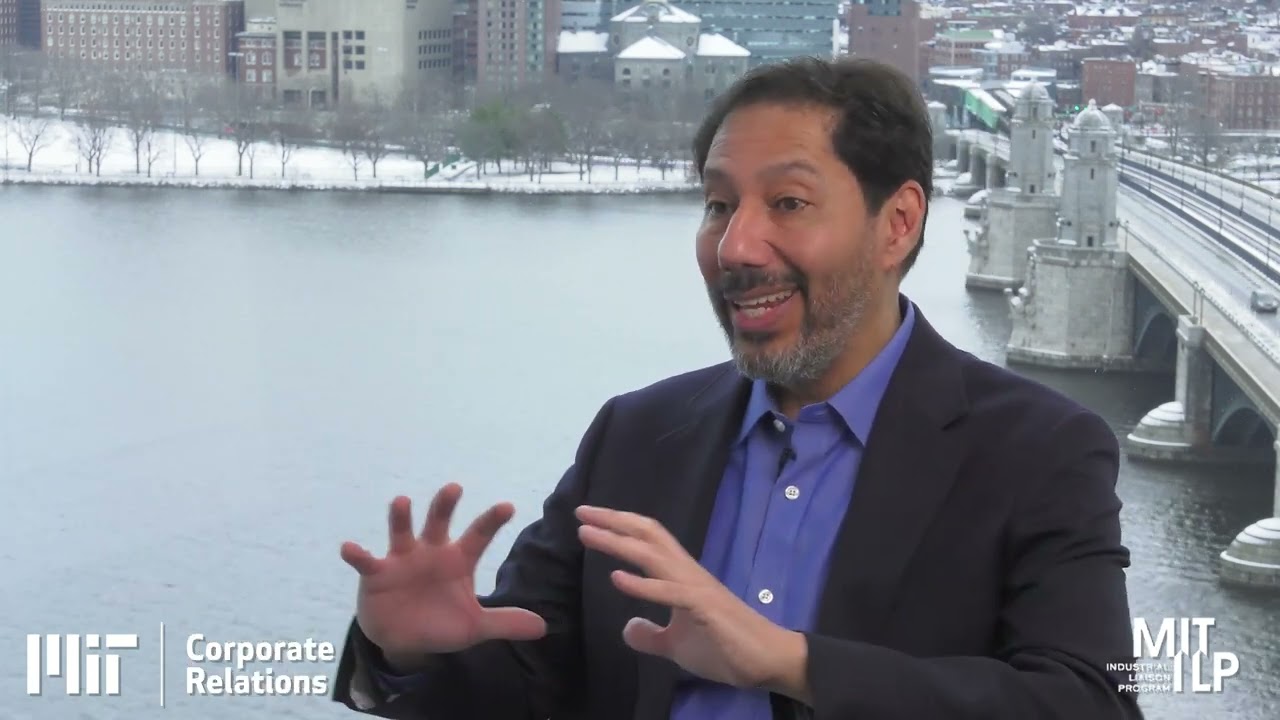

“Putting our arms around what digital transformation is can be difficult to do,” says Abel Sanchez. But as the executive director and research director of MIT’s Geospatial Data Center, that’s exactly what he does with his work in helping industries and executives shift their operations in order to make sense of their data and be able to use it to help their bottom lines.

Handling the pace

Data can lead to making better business decisions. That’s not a new or surprising insight, but as Sanchez says, people still tend to work off of intuition. Part of the problem is that they don’t know what to do with their available data, and there’s usually plenty of available data. Part of that problem is that there’s so much information being produced from so many sources. As soon as a person wakes up and turns on their phone or starts their car, software is running. It’s coming in fast, but because it’s also complex, “it outperforms people,” he says.

As an example with Uber, once a person clicks on the app for a ride, predictive models start firing at the rate of 1 million per second. It’s all in order to optimize the trip, taking into account factors such as school schedules, roadway conditions, traffic, and a driver’s availability. It’s helpful for the task, but it’s something that “no human would be able to do,” he says.

The solution requires a few components. One is a new way to store data. In the past, the classic was creating the “perfect library,” which was too structured. The response to that was to create a “data lake,” where all the information would go in and somehow people would make sense of it. “This also failed,” Sanchez says.

Data storage needs to be re-imaged, in which a key element is greater accessibility. In most corporations, only 10-20 percent of employees have the access and technical skill to work with the data. The rest have to go through a centralized resource and get into a queue, an inefficient system. The goal, Sanchez says, is to democratize the information by going to a modern stack, which would convert what he calls “dormant data” into “active data.” The result? Better decisions could be made.

The first, big step companies need to take is the will to make the change. Part of it is an investment of money, but it’s also an attitude shift. Corporations can have an embedded culture where things have always been done a certain way and deviating from that is resisted because it’s different. But when it comes to data, a new approach is needed. Managing and curating the information can no longer rest in the hands of one person with the institutional memory. It’s not possible. It’s also not practical because companies are losing out on efficiency and productivity, because with technology, “What use to take years to do, now you can do in days,” Sanchez says.

The new player

The above exemplifies what’s been involved with coordinating data along four intertwined components: IoT, AI, the cloud, and security. The first two create the information, which then gets stored in the cloud, but it’s all for naught without robust security. But one relative newcomer has come into the picture. It’s blockchain technology, a term that is often said but still not fully understood, adding further to the confusion.

Sanchez says that information has been handled and organized a certain way with the World Wide Web. Blockchain is an opportunity to be more nimble and productive by offering the chance to have an accepted identity, currency, and logic that works on a global scale. The holdup has always been that there’s never been any agreement on those three components on a global scale. It leads to people being shut out, inefficiency, and lost business.

One example, Sanchez says, of blockchain’s potential is with hospitals. In the United States, they’re private and information has to be constantly integrated from doctors, insurance companies, labs, government regulators, and pharmaceutical companies. It leads to repeated steps to do something as simple as recognizing a patient’s identity, which often can’t be agreed upon. With blockchain, these various entities can create a consortium using open source code with no barriers of access, and it could quickly and easily identify a patient because it set up an agreement, and with it “remove that level of effort.” It’s an incremental step, but one which can be built upon that reduces cost and risk.

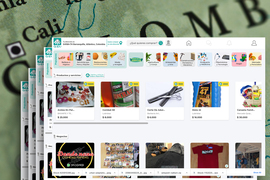

Another example — “one of the best examples,” Sanchez says — is what was done in Indonesia. Most of the rice, corn, and wheat that comes from this area is produced from smallholder farms. For the people making loans, it’s expensive to understand the risk of cultivating these plots of land. Compounding that is that these farmers don’t have state-issued identities or credit records, so, “They don’t exist in the modern economic sense,” he says. They don’t have access to loans, and banks are losing out on potential good customers.

With this project, blockchain allowed local people to gather information about the farms on their smartphones. Banks could acquire the information and compensate the people with tokens, thereby incentivizing the work. The bank would see the creditworthiness of the farms, and farmers could end up getting fair loans.

In the end, it creates a beneficial circle for the banks, farmers, and community, but it also represents what can be done with digital transformation by allowing businesses to optimize their processes, make better decisions, and ultimately profit.

“It’s a tremendous new platform,” Sanchez says. “This is the promise.”