In poorer countries, economic development projects tend to get built with the aid of partner countries and companies, and multilateral development organizations. One line of thought is that such projects work better when the outside partner is also from a lower-income country, what is often referred to as the “Global South.” Suppose the Brazilian cooperation agency works on an agreement to build sewer lines in Mozambique. The existence of “South-South Cooperation” (SSC) means, in theory, that the outside partner will likely produce a better result, compared to the work of a partner with little understanding of its host.

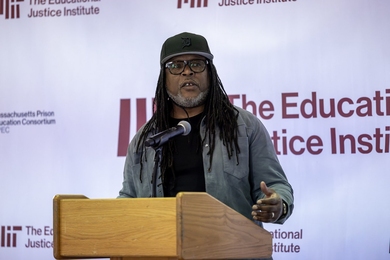

That is a common view, but does it have merit? After years of field research in Mozambique, MIT’s Gabriella Carolini holds a different conclusion. In her view, the best development projects involve close cooperation between proximate peers: the sharing of information among partners, a consistent presence on the ground, non-hierarchical governance, and a drive towards “equity,” in many forms, as a key project goal.

“There has been this idea of South-South Cooperation being better, not just in terms of producing economic growth, but really the fuller sense of what development means,” notes Carolini, an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

Instead, Carolini finds, SSC projects have mixed results. At the same time, project partners from all over the globe are capable of delivering projects well or badly; the key to a successful project is creating many “proximities,” that is, working closely with local residents, experts, and officials to produce benefits.

“It’s not to say you’re not going to get equity in South-South Cooperation, but it’s not because of the label South-South Cooperation,” Carolini adds. “It’s going to be because of all these other factors.”

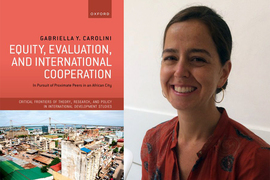

Now Carolini has synthesized her research into a new book, “Equity, Evaluation, and International Cooperation,” just published by Oxford University Press. In it, she details several projects in Mozambique, and arrives at her somewhat heterodox conclusion that, as she writes, “the convenient traditional proxy of geopolitical and hemispheric categories of cooperation predicted little about what drove a cooperation project’s material outcomes.”

On the ground in Maputo

Carolini’s book is the product of extensive field work in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique. In all, she spent about 18 months on the ground in Maputo, from 2009 to 2015, doing research, developing surveys, and speaking extensively with local workers, NGO staff members, government officials, and other stakeholders in development efforts. The projects she examined involved principal partners from Brazil, China, Italy, Japan, and Spain. (In general, the major national players in SSC projects tend to be China, Brazil, India, and South Africa.)

However, Carolini observes in the book, it is not a simple matter to define which projects are examples of South-South Cooperation, and which are not. Suppose you have workers from the Philippines representing a Japanese firm on a project in Mozambique. Does that count as South-South Cooperation? How about a key Colombian staff member working for a Spanish firm in Maputo? To begin with, Carolini finds, textbook definitions often do not apply well to real-world cases.

“What I found on the ground didn’t match, whatsoever, the labels that had been afforded to these different typologies of cooperation,” Carolini says.

Indeed, she adds, “The reality is messier. There’s a great deal of what I call ‘turbidity’ [cloudiness] in the cooperation space. The actual composition of international development cooperation at the project level reveals the misleading nature of the labels, which speak to macro-level politics, perhaps, but not project-level realities.”

Moreover, as Carolini details in the book, development projects spearheaded by the same country can work out very differently. Brazil would seem a good development partner for Mozambique, sharing a language and perhaps solidarity as another former Portugese colony. But two projects with Brazilian partners that Carolini studied had underwhelming outcomes. One, attempting to establish a workers’ cooperative among trash pickers in Maputo’s main city dump, failed to gain traction as intended. Another, a sewer and drainage project, ran into planning and financing problems, and ended up being completed by an experienced Italian NGO called AVSI.

“Even with the same national project partners, there were differences at the project level in in how they were governed, in the theories of practice that people brought in, in their embeddedness, and how present they [foreign staff] were,” Carolini says. “Those things mattered in terms of the equity that is promised in terms of South-South cooperation.”

Meanwhile, some non-SSC projects showed cooperative promise. One Japan-backed project involving waste and recycling in Maputo was not an SSC effort. Still, Carolini found that the Japanese staff were, in certain ways, very attentive to local feedback, modifying project details like the kind of composting that was possible in Maputo.

What works best?

Through this kind of close observation and critical thinking, Carolini has developed her own views on what helps projects succeed. As she writes in the book, after the scholar Peter Marcuse, “it is not enough to simply expose that which does not work.”

In general, Carolini believes, the more cooperative projects are — the more “proximities” they contain — the better they will be in broad terms. That’s because the goal of development projects in not merely material gains; it is also the joint development and transfer of know-how, experience, and high-level learning, among all parties in the project, which also matter. If increasing local equity is the project goal from the start — not just in material terms, but in matters of governance and knowledge-sharing — then the project is far more likely to be a success.

To reinforce this in international development circles, from the United Nations and World Bank to NGOs, Carolini contends, the development world needs to change the way it evaluates its efforts, shifting away from a material focus to the values of equitable learning and governance.

“What I’m trying to advocate is that we’re a little bit more nuanced in our evaluation of projects,” Carolini says. She adds: “Perhaps cooperation partners and the design of projects will pay attention, so that you have a more continuous system where equity is considered at all stages of a project.”

And while Carolini would like anyone interested in urbanism, development, or Africa to become engaged in the book, she hopes her critique and conclusions about development will find an audience among professionals in the field.

“What I would love is for any international partner, whether they’re from the North or the South, to be paying attention to some of these proximities that matter in advancing equity,” Carolini says.