In June of 2018, telescopes around the world picked up a brilliant blue flash from the spiral arm of a galaxy 200 million light years away. The powerful burst appeared at first to be a supernova, though it was much faster and far brighter than any stellar explosion scientists had yet seen. The signal, procedurally labeled AT2018cow, has since been dubbed simply “the Cow,” and astronomers have catalogued it as a fast blue optical transient, or FBOT — a bright, short-lived event of unknown origin.

Now an MIT-led team has found strong evidence for the signal’s source. In addition to a bright optical flash, the scientists detected a strobe-like pulse of high-energy X-rays. They traced hundreds of millions of such X-ray pulses back to the Cow, and found the pulses occurred like clockwork, every 4.4 milliseconds, over a span of 60 days.

Based on the frequency of the pulses, the team calculated that the X-rays must have come from an object measuring no more than 1,000 kilometers wide, with a mass smaller than 800 suns. By astrophysical standards, such an object would be considered compact, much like a small black hole or a neutron star.

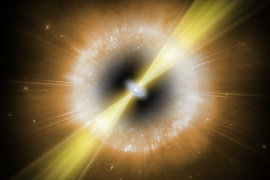

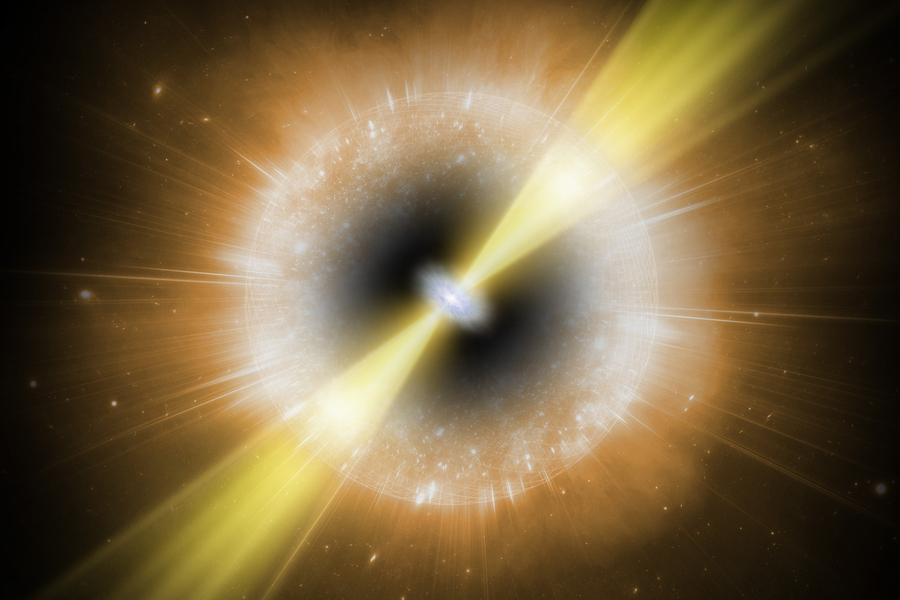

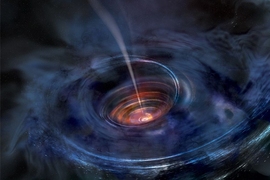

Their findings, published today in the journal Nature Astronomy, strongly suggest that AT2018cow was likely a product of a dying star that, in collapsing, gave birth to a compact object in the form of a black hole or neutron star. The newborn object continued to devour surrounding material, eating the star from the inside — a process that released an enormous burst of energy.

“We have likely discovered the birth of a compact object in a supernova,” says lead author Dheeraj “DJ” Pasham, a research scientist in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “This happens in normal supernovae, but we haven’t seen it before because it’s such a messy process. We think this new evidence opens possibilities for finding baby black holes or baby neutron stars.”

“The core of the Cow”

AT2018cow is one of many “astronomical transients” discovered in 2018. The “cow” in its name is a random coincidence of the astronomical naming process (for instance, “aaa” refers to the very first astronomical transient discovered in 2018). The signal is among a few dozen known FBOTs, and it is one of only a few such signals that have been observed in real-time. Its powerful flash — up to 100 times brighter than a typical supernova — was detected by a survey in Hawaii, which immediately sent out alerts to observatories around the world.

“It was exciting because loads of data started piling up,” Pasham says. “The amount of energy was orders of magnitude more than the typical core collapse supernova. And the question was, what could produce this additional source of energy?”

Astronomers have proposed various scenarios to explain the super-bright signal. For instance, it could have been a product of a black hole born in a supernova. Or it could have resulted from a middle-weight black hole stripping away material from a passing star. However, the data collected by optical telescopes haven’t resolved the source of the signal in any definitive way. Pasham wondered whether an answer could be found in X-ray data.

“This signal was close and also bright in X-rays, which is what got my attention,” Pasham says. “To me, the first thing that comes to mind is, some really energetic phenomenon is going on to generate X-rays. So, I wanted to test out the idea that there is a black hole or compact object at the core of the Cow.”

Finding a pulse

The team looked to X-ray data collected by NASA’s Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER), an X-ray-monitoring telescope aboard the International Space Station. NICER started observing the Cow about five days after its initial detection by optical telescopes, monitoring the signal over the next 60 days. This data was recorded in a publicly available archive, which Pasham and his colleagues downloaded and analyzed.

The team looked through the data to identify X-ray signals emanating near AT2018cow, and confirmed that the emissions were not from other sources such as instrument noise or cosmic background phenomena. They focused on the X-rays and found that the Cow appeared to be giving off bursts at a frequency of 225 hertz, or once every 4.4 milliseconds.

Pasham seized on this pulse, recognizing that its frequency could be used to directly calculate the size of whatever was pulsing. In this case, the size of the pulsing object cannot be larger than the distance that the speed of light can cover in 4.4 milliseconds. By this reasoning, he calculated that the size of the object must be no larger than 1.3x108 centimeters, or roughly 1,000 kilometers wide.

“The only thing that can be that small is a compact object — either a neutron star or black hole,” Pasham says.

The team further calculated that, based on the energy emitted by AT2018cow, it must amount to no more than 800 solar masses.

“This rules out the idea that the signal is from an intermediate black hole,” Pasham says.

Apart from pinning down the source for this particular signal, Pasham says the study demonstrates that X-ray analyses of FBOTs and other ultrabright phenomena could be a new tool for studying infant black holes.

“Whenever there’s a new phenomenon, there’s excitement that it could tell something new about the universe,” Pasham says. “For FBOTs, we have shown we can study their pulsations in detail, in a way that’s not possible in the optical. So, this is a new way to understand these newborn compact objects.”

This research was supported, in part, by NASA.