What happens when you put a group of experienced, high-powered champions of innovation and a bunch of MIT students with crazy-smart technology ideas in the same room? Short answer: They learn from each other. Longer answer: the new MIT Sandbox Innovation Fund.

Launched last January, MIT Sandbox is a new program for all MIT students that provides mentoring, customized educational experiences, and seed funding of up to $25,000 for new ideas. The program is structured to accommodate students who are at different stages along the spectrum of completion with their ideas, so that as they progress they become eligible for higher levels of financial support.

“Sandbox isn’t a competition, and it isn’t about picking winners,” says Ian A. Waitz, dean of MIT’s School of Engineering and the faculty director of the program. “It’s about creating opportunities for any MIT student interested in learning about innovation through doing.”

Making the Pitch

Malena Ohl ’16 did her best to keep this in mind at the inaugural meeting of the Sandbox program’s funding board on April 26. Everything felt surreal as she entered a conference room with a sweeping view of the Boston skyline and a collection of high-profile people waiting for her to tell them why her idea should be funded.

She took a deep breath and delivered the pitch for her team, Stello, which is developing a wearable medication dispenser. All the while, she watched the facial expressions before her, thinking, “Do they like it?”

Student teams had five minutes to make their case and four minutes to answer questions posed by a discerning audience. There were successful innovators, entrepreneurs, investors, and business leaders, including representatives from Amazon, Philips, Xerox, Polaris, GettyLab, General Catalyst, OCP Group, and MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

Some board members were dressed in jeans and sneakers, and others were in designer suits; they ranged in age, gender, ethnicity, and affect. Yet collectively they had two things in common: They had experience nurturing a brilliant idea into a final product with a niche in the marketplace and power in the world — and they were there to help students learn the same.

Students founds themselves addressing, or struggling with, questions about business plans, prototypes, marketing, financing, logistics, regulatory processes, and supply costs. Had the team contacted others in the industry? How was the product better than market competitors?

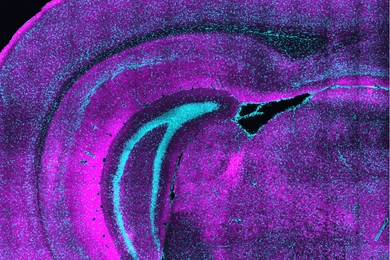

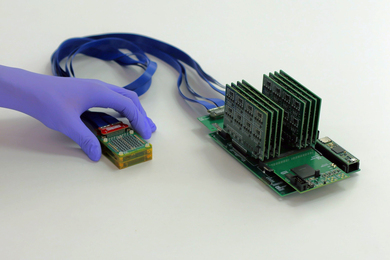

Strategies varied. Lux Labs, the product of Yichen Shen PhD ’16 and Spencer Powers MBA ’16, showed off a working prototype of an electronic display that triples brightness, conserves energy, and dynamically regulates infrared light passage. BioDomus, a team of students — Francis Lee, Ang Cui PhD ’20, Robert Hinshaw PhD, ’20 and Marc-Joseph Antonini PhD ’20 — building bioreactors for cell culture, impressed board members with their technology and, notably, their qualification of their target market: The demand for cell culture in academia and industry is increasing at 7.5 percent each year. Hidden Switch, a competitive video game startup from Benjamin Berman SM ’17 and Sen Chan ’18, gave a presentation about a first-person shooter game, Crucible, that was so steeped in industry knowledge that board members felt almost unable to judge them but believed they really knew what they were up to.

What’s right for Sandbox

The parallel, 31-presentation sessions lasted four hours, but funding board members emerged eager to discuss the presentations and revisit their earlier discussions about funding criteria. Some differences persisted, and new ones surfaced around what types of projects are right for Sandbox.

A key issue was whether to provide support for groups that appeared to be already well on their way. Many teams had received significant grants from other funding programs. Although Sandbox complements and integrates those experiences, the amount of previous backing mattered to nearly all board members. However, opinions about how much was too much varied greatly.

Take Hydroswarm. Founder Sampriti Bhattacharya, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, designed an underwater drone as part of her doctoral thesis. In 2015, she transformed that research into a company — and Exxon, Google, and the Department of Defense came knocking. Recently, Forbes listed Bhattacharya among its 30 most successful entrepreneurs under 30. The students in Hydroswarm do not intend to pursue commercial possibilities until after graduation, and they need money to work on an advanced prototype for demos. In 2015, they won $15,000 from the MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition and $50,000 from MassChallenge.

Board members were torn. Some felt Hydroswarm was just too advanced for Sandbox while others called it a great fit with high educational value, cross-disciplinary strengths, and environmental benefits. Ultimately, they decided to award the group $10,000.

At the end of the day, the board’s decisions led to the distribution of $350,000 among 108 teams. Only a portion of those pitched that day — an opportunity that requires instruction and preparation work beforehand. Twenty-five teams received more than $10,000, and the rest got between $1,000 and $5,000. Eight teams received the full amount they requested.

Students interviewed after the presentations say Sandbox offers far more than financial support. They described its help with honing a company message; acquiring insider knowledge via advisors; and, above all, developing an informed ability to truly think like an innovator.

Ohl, who made the presentation for Stello, was relieved to discover that board members responded to her pitch with warmth and encouragement. “They don’t make judgments about your idea,” she said. “Most startups fail, and lots of innovation competitions reward the winners but do nothing to help develop those still learning.”

Dexter Ang ’05 from ALS Communication Technology, which aims to create low-cost wireless communication technology for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, said Sandbox mentors guide students through the startup process. “Sandbox is a catalyst that will help accelerate my journey,” he said. “It is very proactive in helping you develop the mentality you need to be successful.”

Teams also said the program encourages a kind of focus. “Sandbox creates a formal system that helps us prioritize. It creates a structure that motivates us to carve out our time to follow through on our ideas,” said Berman from Hidden Switch.

Sandbox Executive Director Jinane Abounadi SM ’90, PhD ’98, who previously held leadership positions in two successful Boston-based startups, said the program is multifaceted. “We are supporting a community of innovators — and in turn, they support each other. The peer experience is a crucial element. They learn to draw energy and expertise from one another, as well as from us.”

The desire to educate prevailed. Even when board members felt skeptical about technical delivery, business models, and market viability, they leaned toward supporting student ambitions. They often suggested partial funding, recommending the team rethink a particular approach.

A remark by Sophie Vandebroek, the chief technology officer of Xerox Corporation, reflected the spirit of their approach: “Let’s help them keep going."