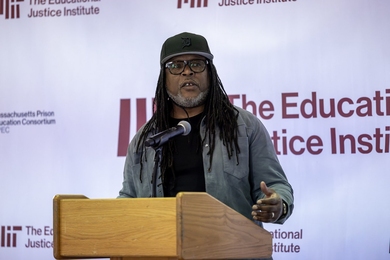

The research, presented in a paper by MIT economist David Autor, along with economist David Dorn, helps add nuance to the nation’s job picture. While a widening gap between highly trained and less-trained members of the U.S. workforce has previously been noted, the current study shows in more detail how this transformation is happening in stores, restaurants, nursing homes, and other places staffed by service workers.

Specifically, workers in many types of middle-rank positions — such as skilled production-line workers and people in clerical or administrative jobs — have had to migrate into jobs as food-service workers, home health-care aides, child-care employees, and security guards, among other things.

“This polarization that we see is being driven by the movement of people out of middle-skill jobs and into services,” says Autor, a professor of economics at MIT. “The growth in service employment isn’t that large overall, but when you look at people with a noncollege education, it’s a very sharp increase, and it’s very concentrated in places that were initially specialized in the more middle-skill activities.”

Indeed, the portion of all U.S. labor hours logged by service workers grew by 30 percent between 1980 and 2005. That growth has not been enough to accommodate all the displaced workers from other industries, but it clearly is where some job-seekers have wound up: For instance, people working as machine operators and assemblers constituted 9.9 percent of U.S. labor hours in 1980, compared to 4.6 percent in 2005. Meanwhile, service occupations comprised 9.9 percent of labor hours in 1980, and are 12.9 percent today.

‘Not an improvement in job quality’

The transition to service-sector jobs presents mostly bad news — along with a bit of good news — for people making the shift. The bad news, in part, is that service-sector positions, beyond the inherent difficulties of some of the jobs, tend to come with less leverage and more insecurity for employees.

“This is not an overall improvement in job quality,” Autor observes. “The problem with many of these jobs is they require fairly generic skill sets, which means workers have limited negotiating power and are fairly interchangeable. These are not, in general, attractive jobs.”

That said, the good news is that service-sector jobs have seen surprising growth in wages since 1980: an average of 6.4 percent per decade, adjusted for inflation. That has happened despite the increased supply of workers available for service-sector jobs, which should, in theory, depress those wages.

Thus the paper also teases out an issue of interest to economic researchers, concerning the reasons for this wage increase. Autor and Dorn suggest that increased productivity has lowered the prices of some goods, allowing people to pay more for some services, such as home health care.

Additionally, after examining 700 “commuting zones” around metropolitan areas in the United States, the study also finds that the change to service-sector jobs has happened both in traditional industrial areas, such as Chicago and Detroit, and in areas with a high proportion of office jobs, such as New York and San Francisco. In both cases, technological advances have automated a significant number of existing jobs.

“This is a case where technology, at present, is playing a larger role in eliminating middle-skill activities than it is in eliminating low-skill activities,” Autor explains.

More standards to help service-sector workers?

The paper, “The Growth of Low Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market,” was published in the American Economic Review. Dorn, an economist at the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies in Madrid, is currently a visiting professor at Harvard University.

The paper has been well received by other scholars. “The problems caused by the stagnation or even decline of the incomes of the middle class is one of the defining issues of the moment,” says Alan Manning, a professor at the London School of Economics, who has read the study. “This paper provides the most complete account to date of the causes of this polarization in the U.S. labor market, fingering technological change and consumer preferences as the root cause. Next stop: What can we do about it?”

In Autor’s view, studies of this kind have clear implications for policymakers: The findings, he says, can “alert people to the changing opportunity set faced by contemporary workers. I think that is relevant to education policy and labor standards.”

For instance, he suggests, recognizing that an increasing number of workers are in the service sector might lead some policymakers to endorse regulations about hours and working standards that would help these parts of the American workforce.

“It seems like people in these jobs are treated almost gratuitously badly,” Autor says. “If you work in retail, it’s possible you won’t even know your hours until the beginning of the week. … Having uncertainty about your schedule from week to week, [when] you need to get your kids off to school, makes life that much tougher. … These jobs offer flexibility, but mostly to the employer.”

The United States, he adds, “is unusual in offering almost no standards in this type of work.” And while such standards would impose some costs on employers, Autor suggests that those trade-offs could be part of a larger debate about employment today.

The findings also feed into a larger project Autor is pursuing, about the extent to which wealth and achievement are linked from generation to generation.

“Changes in labor demand have very serious social ramifications, not just in terms of work and employment, but for household structure and the transmission of disadvantage versus the transmission of achievement,” Autor says.