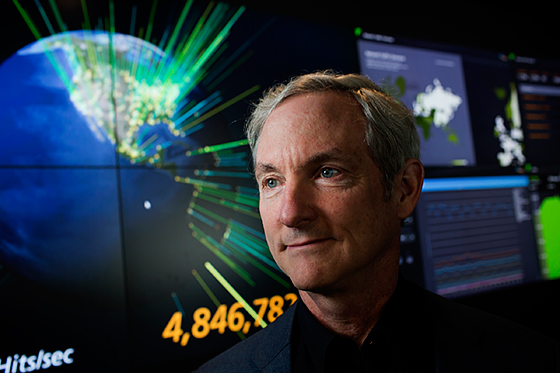

Tom Leighton, co-founder and CEO of Akamai Technologies Photo: M. Scott Brauer

Second in a two-part series (Read part one: "Birthplace of biotech")

At 8 Cambridge Center — in the heart of Kendall Square, a stone’s throw from MIT — sits the headquarters of Akamai Technologies, a web-services company that provides one of the world’s largest distributed-computing platforms. Much as nearby Biogen Idec got its start during Kendall’s rebirth as a life-sciences hub in the 1970s and 1980s, Akamai opened during the tech boom of the late 1990s.

Akamai has moved its operations to several different locations in Kendall Square since its 1998 founding, “but never more than a few blocks from MIT,” says co-founder and CEO Tom Leighton, a former professor of applied mathematics at MIT. (He stopped teaching at the Institute after becoming Akamai’s CEO in January.)

Indeed, MIT was a big part of why the company opened and stayed in Kendall Square: Many of the company’s first employees, engineering and technology licenses came from the Institute. In Kendall, Leighton says, “You are at the epicenter in terms of the university, in terms of MIT, and Harvard, and that’s special. So it makes perfect sense that you grow around that.”

Leighton and Akamai co-founder Daniel Lewin ’98 — along with others from MIT, including a postdoc and students in the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program — worked on the company’s early, novel coding, called consistent hashing, in what is now MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Consistent hashing would evolve into the core of Akamai’s commercial technology, essentially duplicating a client’s online content — HTML code, media, software downloads, and so on — and redirecting its customers to an Akamai server with the best connection for faster download times and fewer vulnerabilities to network issues.

From concept to company

During Akamai’s earliest phases, Leighton’s group had no intention of founding a company; that decision was spurred by the team’s 1997 participation in the $50K Entrepreneurship Competition (the precursor to today’s $100K contest). “It was through that process that we learned about forming a company and met people who would be helpful to do that,” says Leighton, who served as Akamai’s chief scientist for 15 years before becoming CEO. “In late ’98, we decided to form a company, seeing it as the only way to get the technology used in practice.”

Since then, the firm has grown and grown: As of 2012, Akamai has roughly $1.3 billion in annual revenue and employs more than 3,000 employees in some 50 locations worldwide. Its network houses the most-distributed cloud-optimization platform, with more than 127,000 servers in 81 countries.

As Akamai grew, Leighton watched tech firms and other businesses sprout up around its headquarters, transforming Kendall Square from a “rundown, tired industrial area” to a veritable tech mecca. Leighton says Kendall’s high-tech infrastructure and innovative culture is now rivaled only by Silicon Valley.

“Outside that, I don’t see anywhere better,” Leighton says. “The more [the infrastructure] draws people to the area, it creates more of a talent pool to draw from. And we’re part of a vibrant community with a lot of ideas, the desire to start something different. That’s the type of culture we want to have at Akamai. You want to have people in the ecosystem and workforce like that: It keeps the company young and agile.”

Akamai has been a reigning leader in its field for years. But growth inevitably brings competition: Kendall newcomer Amazon is not only a potential competitor for Akamai’s service, but also for its talent. Leighton says he isn’t worried — in fact, he says, competition is another upside of a vibrant Kendall Square.

“We want to be a better place to work than those guys,” Leighton says. “So we compete for employees, when they’re right next door. It keeps you on your toes.”

The ecosystem has helped fuel Akamai, but does the recent boom — which comes with an influx of big businesses, and a resulting rise in prices — threaten to dissuade startups from moving to Kendall Square? Leighton thinks not: “Here you can get all the talent and resources you need and really focus on building a company,” he says.

HubSpot, rising tech star

An example of Kendall Square’s ongoing lure is HubSpot, an inbound-marketing software company co-founded in 2006 by MIT Sloan School of Management graduates Brian Halligan MBA ’05 and Dharmesh Shah SM ’06. The firm’s “inbound marketing,” a marketing strategy that helps companies leverage social media and other digital tools to attract customers, has itself attracted more than 8,600 customers in 50-plus countries. It recently pushed past the 500-employee mark, opened a branch in Dublin, and made business headlines when it reported an 82 percent growth in annual revenue in 2012, to $52.5 million.

Brian Halligan MBA ’05, co-founder of HubSpot Photo: M. Scott Brauer

Although large now, HubSpot operated for four years in Kendall Square’s startup haven, the Cambridge Innovation Center — which was founded in 1999, and now houses more than 450 startups, many MIT-affiliated — before moving half a mile up the road.

Despite Kendall’s rising prices, Halligan says it was a “no-brainer” for his small company to remain local rather than heading off to Silicon Valley. “In the Valley, you’re a small fish in a large pond,” he says. “And talent is more expensive. The war for talent is heated there. There’s something in the culture of the Valley: It’s entrepreneurial and that makes it great, but it’s also hard to retain people. We would have had a much harder time building HubSpot if we moved there.”

HubSpot set up shop in Kendall Square early enough for Halligan to witness today’s innovation ecosystem spring up around his company; that atmosphere, he says, helps feed his company. “It’s nice being around a lot of other smart people,” Halligan says. “There’s certainly an energy and a buzz that’s infectious. It’s very hard to quantify that stuff, but there’s something to it: It’s a very attractive place to work.”

The company was hatched when Halligan and Shah realized that the “old-school” marketing techniques used in most businesses — cold-calling, online ads, email, and so on — weren’t working. “The playbook was the same everywhere, and the problem was the playbook was broken,” Halligan says.

So the two changed the playbook: They created software and services that now help businesses convert to HubSpot’s inbound-marketing strategy, which uses Facebook, blogs, Twitter, and other social media to gather leads. The concept involves several stages: attract traffic to websites; convert visitors to leads; convert leads to sales; turn customers into repeat, higher-margin customers; and analyze for continuous improvement. “It’s like a gym membership,” Halligan says. “The more you use it, the better shape you get in.”

Despite its growth, HubSpot plans to remain headquartered near Kendall Square, Halligan says — not only for access to MIT’s intellectual capital, but also to help promote Boston as the next big innovation hub. For Halligan, this goal is personal: “When I was a kid, my dad worked for BBN [Technologies], another MIT-founded company,” he says. “When he was my age, Boston dominated. Then, we missed the PC, then the Internet. But I want to bring Boston back. I want HubSpot to be an anchor company, if we can pull it off.”

So, to all tech startups seeking an area to develop, Halligan says, “You should stay in Boston. There’s plenty of access to capital, plenty of know-how, and tons of talent.”