The race to find exoplanets — planets outside our solar system — continues to quicken. Last week NASA researchers announced that the agency's new space telescope, Kepler, has discovered five new exoplanets, expanding the number of known exoplanets to 422, an increase of about 25 percent in the past year alone. A satellite proposed by MIT researchers could accelerate these discoveries and even detect hundreds of Earth-sized planets — a few of which could be natural candidates for life.

The MIT team, led by Senior Research Scientist George Ricker of the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, is awaiting NASA approval for the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which would conduct the first-ever spaceborne survey of transiting planets, or planets that pass in front of their host stars as seen from Earth. By searching a region of the sky 400 times larger than revealed by Kepler's scope, TESS would observe 2.5 million of the closest and brightest stars when it is launched. Ricker's team predicts it would detect between 1,600 and 2,700 planets within two years, including between 100 and 300 small planets.

"Although TESS should find hundreds of small planets, only a handful would be in the 'habitable zone' and would be natural candidates for life," said MIT assistant professor of physics Joshua Winn, who is part of Ricker's team.

Most of the 422 exoplanets discovered to date (and catalogued here by astronomer Jean Schneider of the Paris Observatory) are hot Jupiters, giant planets that are likely inhospitable to biological activity. TESS would focus on finding smaller planets similar in size to Earth. Using six wide-angled, high-precision cameras to scan the sky for temporary drops in brightness caused when a planet passes in front of its star, TESS would measure the light obscured by a planet as it transits. TESS would then catalog the light curves caused by these transits so that follow-up work through ground observations and high-resolution spectroscopy can determine the planet's mass, radius and density. Spectroscopic studies with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope of bright exoplanets found by TESS could reveal details about a planet's atmosphere, such as whether water or carbon dioxide exist.

Ricker's team disclosed details about TESS in its first comprehensive public presentation at the annual American Astronomical Society conference on Jan. 6 in Washington.

A mix of science and guesswork

Winn and fellow MIT professor Sara Seager explained the science behind their estimate that TESS could detect as many as 2,700 planets, including several hundred Earth-sized planets.

Estimating how many planets TESS would find is a complicated process that Winn compares to counting how many people in a crowded stadium are waving cigarette lighters at the moment you take off a blindfold. The number would depend on how far away your eyes can detect a flame, as well as how many people are actually waving lighters at that moment. "The first question is a physics question," Winn explained. "The second question is unanswerable unless you happen to know exactly how many people carry lighters and are likely to wave them around." Add to that the fact that the flame from each lighter may have a different brightness, just as stars may differ in brightness and planets may differ in size. These factors had to be taken into account to estimate how many planets TESS might find.

To reach their estimate, the scientists made an educated guess about how many of these stars actually have planets orbiting them, based on information already known about giant planets, such as orbital distance and size. "It's a bit more complicated, but we assume in this case that all planets are equally common, and that the abundance is about the same as the abundance of giant planets," Winn said of the several hundred giant exoplanets that have been found to date. The scientists then considered certain properties of the stars and of TESS, such as stellar luminosity and the size of the camera lenses, to estimate how many Earth-like planets will transit their host stars from a distance that TESS could probe.

Schneider said that although he hasn't examined the numbers in detail, he believes the estimate and methodology are "a reasonable order of magnitude" given his experience with other satellites searching for exoplanets.

While the overall estimate is not surprising to the MIT team, it is the prospect of finding 100 to 300 Earth-sized planets that tantalizes astronomers.

The TESS project began in 2007 when NASA announced its Small Explorer (SMEX) satellite program to provide funding for science missions using small to mid-sized spacecraft. In June 2008, NASA selected Ricker's team, which includes scientists from MIT, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and NASA-Ames Research Center, to receive $750,000 for an initial feasibility study. A year later, NASA elected not to proceed with TESS, but said the MIT-led group and other teams could submit new proposals later this year.

Ricker's team is currently working on implementing modifications to the original proposal. "We are really making the case for NASA and the astronomy community as a whole to establish that this must be the next big leap that will be made in this field," Ricker said.

TESS is part of a joint effort between the Kavli Institute, the Department of Physics and the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at MIT to study exoplanets. The project also involves scientists at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, NASA Ames Research Center, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network.

Researchers say proposed satellite could represent astronomy’s ‘next big leap’ — one that may help find signs of life elsewhere in the universe.

Publication Date:

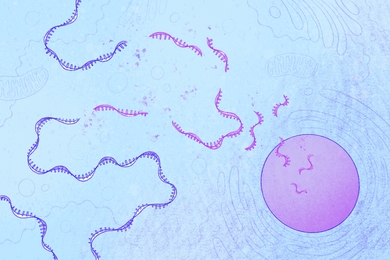

Caption:

If approved, TESS would spend two years searching the sky for planets orbiting roughly 2.5 million nearby stars.

Credits:

Image: Teague Soderman