Magnetic resonance imaging, first developed in the early 1970s, has become a standard diagnostic tool for cancer, cardiovascular disease and neurological disorders, among others. MRI is ideally suited to medical imaging because it offers an unparalleled three-dimensional glimpse inside living tissue without damaging the tissue. However, its use in scientific studies has been limited because it can’t image anything smaller than several cubic micrometers.

Now scientists are combining the 3-D capability of MRI with the precision of a technique called atomic force microscopy. This combination enables 3-D visualization of tiny specimens such as viruses, cells and potentially structures inside cells — a 100-million-fold improvement over MRI used in hospitals.

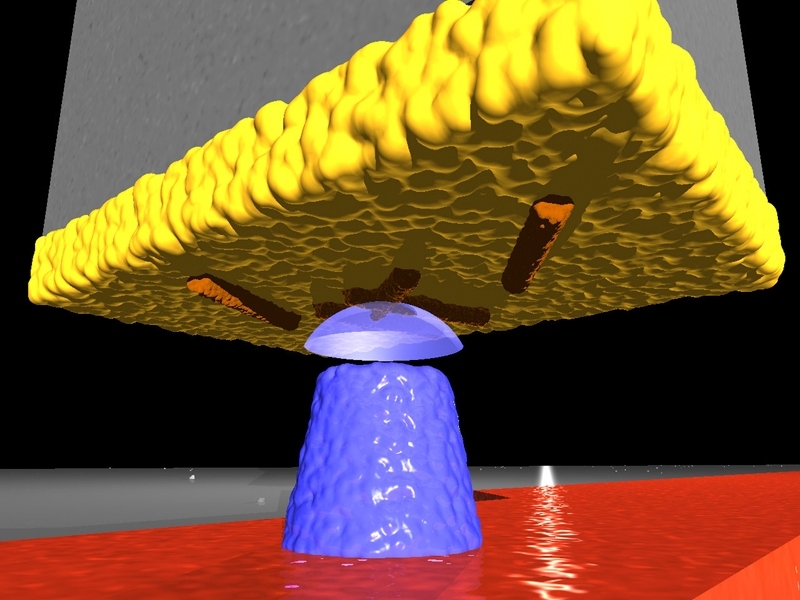

Last year, Christian Degen, MIT assistant professor of chemistry, and colleagues at the IBM Almaden Research Center, where Degen worked as a postdoctoral associate before coming to MIT, used that strategy to build the first MRI device that can capture 3-D images of viruses. Last weekend, their paper reporting the ability to take an MRI image of a tobacco mosaic virus was awarded the 2009 Cozzarelli Prize by the National Academy of Sciences, for scientific excellence and originality in the engineering and applied sciences category.

“It’s by far the most sensitive MRI imaging technique that has been demonstrated,” says Raffi Budakian, assistant professor of physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who was not part of the research team.

Using nanoscale MRI to reveal the 3-D shapes of biological molecules offers a significant improvement over X-ray crystallography, which was key to discovering the double-helix structure of DNA but is not well suited to proteins because they are difficult to crystallize, says Budakian. “There’s really no other technique that can go in molecule by molecule and determine the structure,” he says. Figuring out such structures could help scientists learn more about diseases caused by malformed proteins and identify better drug targets.

Improving on MRI

Traditional MRI takes advantage of the very faint magnetic signals emitted by hydrogen nuclei in the sample being imaged. When a powerful magnetic field is applied to the tissue, the nuclei’s magnetic spins align, generating a signal strong enough for an antenna to detect. However, the magnetic spins are so weak that a very large number of atoms (usually more than a trillion) are needed to generate an image, and the best possible resolution is about three millionths of a meter (about half the diameter of a red blood cell).

In 1991, theoretical physicist John Sidles first proposed the idea of combining MRI with atomic force microscopy to image tiny biological structures. IBM physicists built the first microscope based on that approach, dubbed magnetic resonance force microscopy (MRFM), in 1993.

Since then, researchers including Degen and his IBM colleagues have improved the technique to the point where it can produce 3-D images with resolution as low as five to 10 nanometers, or billionths of a meter. (A human hair is about 80,000 nanometers thick.)

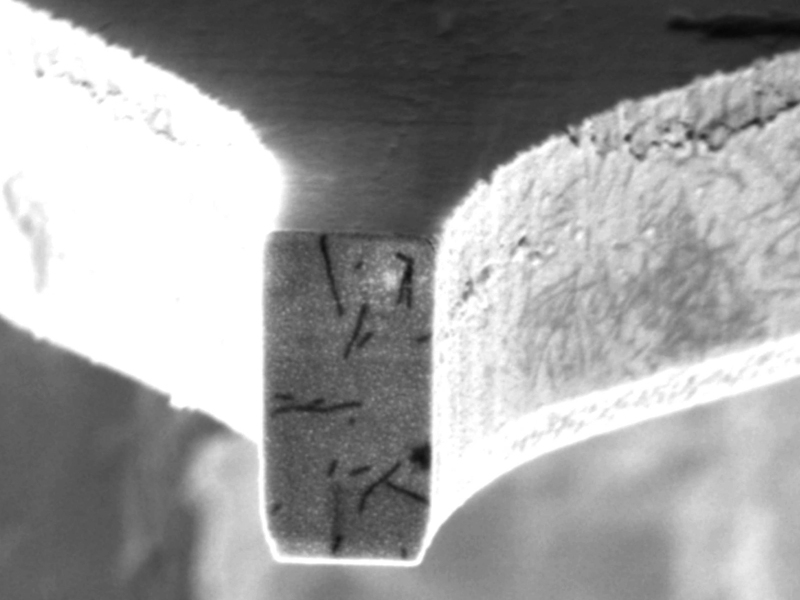

With MRFM, the sample to be examined is attached to the end of a tiny silicon cantilever (about 100 millionths of a meter long and 100 billionths of a meter wide). As a magnetic iron cobalt tip moves close to the sample, the atoms’ nuclear spins become attracted to it and generate a small force on the cantilever. The spins are then repeatedly flipped, causing the cantilever to gently sway back and forth in a synchronous motion. That displacement is measured with a laser beam to create a series of 2-D images of the sample, which are combined to generate a 3-D image.

MRFM resolution is nearly as good (within a factor of 10) of the resolution of electron microscopy, the most sensitive imaging technique that biologists use today. However, unlike electron microscopy, MRFM can image delicate samples like viruses and cells without damaging them.

New targets

Degen, who became interested in pursuing new MRI techniques after seeing an electron microscope demonstration in college, says his work could help structural biologists discover new drug targets for viruses.

“Usually if you want to find out how things work, you have to find the structure. Otherwise you don’t know how to design drugs,” he says. “You’re operating in a blind spot.”

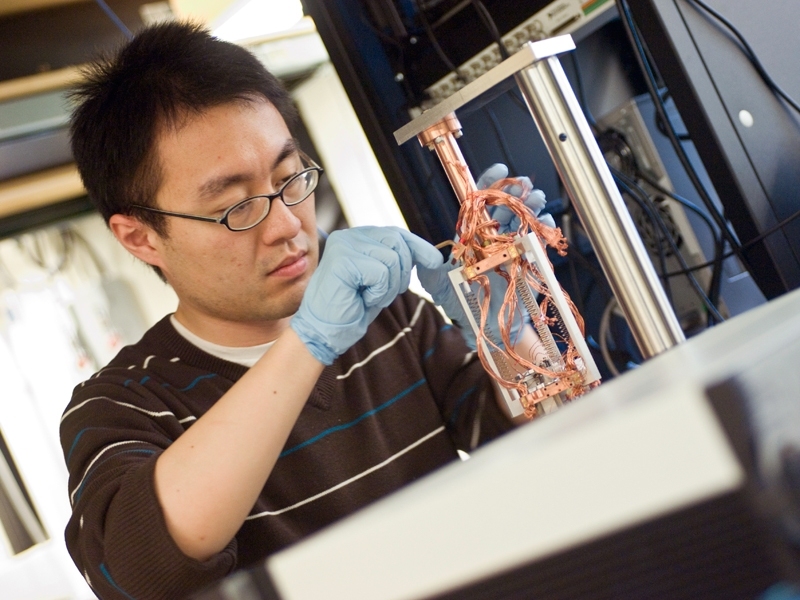

Degen and chemistry graduate student Ye Tao are now building an MRFM microscope in the basement of MIT’s Building 2. When completed, the microscope will be one of just a handful of its kind in the world. Most of the parts are in place and functioning, but Degen and Tao still need to obtain the refrigeration unit that will cool the system to just above absolute zero. The system must be cooled to 50 millikelvins to minimize thermal vibrations, which interfere with the cantilever’s magnet-induced displacement signal.

Degen hopes to receive the refrigeration unit in late May or early June, but shipment could be delayed by an ongoing shortage of helium isotopes, which are required to achieve the necessary cooling. If all goes according to plan, the microscope could be generating images by the end of this year.

Degen and two of his students are also pursuing another new approach to nanoscale MRI. This approach uses fluorescence instead of magnetism to image samples. Their new microscope replaces the magnetic tip with a diamond that has a defect in its crystal structure. The defect, known as a nitrogen-vacancy defect, functions as a sensor because its fluorescence intensity is altered by interactions with magnetic spins. This setup does not have to be cooled, so samples can be imaged at room temperature.

Now scientists are combining the 3-D capability of MRI with the precision of a technique called atomic force microscopy. This combination enables 3-D visualization of tiny specimens such as viruses, cells and potentially structures inside cells — a 100-million-fold improvement over MRI used in hospitals.

Last year, Christian Degen, MIT assistant professor of chemistry, and colleagues at the IBM Almaden Research Center, where Degen worked as a postdoctoral associate before coming to MIT, used that strategy to build the first MRI device that can capture 3-D images of viruses. Last weekend, their paper reporting the ability to take an MRI image of a tobacco mosaic virus was awarded the 2009 Cozzarelli Prize by the National Academy of Sciences, for scientific excellence and originality in the engineering and applied sciences category.

“It’s by far the most sensitive MRI imaging technique that has been demonstrated,” says Raffi Budakian, assistant professor of physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who was not part of the research team.

Using nanoscale MRI to reveal the 3-D shapes of biological molecules offers a significant improvement over X-ray crystallography, which was key to discovering the double-helix structure of DNA but is not well suited to proteins because they are difficult to crystallize, says Budakian. “There’s really no other technique that can go in molecule by molecule and determine the structure,” he says. Figuring out such structures could help scientists learn more about diseases caused by malformed proteins and identify better drug targets.

Improving on MRI

Traditional MRI takes advantage of the very faint magnetic signals emitted by hydrogen nuclei in the sample being imaged. When a powerful magnetic field is applied to the tissue, the nuclei’s magnetic spins align, generating a signal strong enough for an antenna to detect. However, the magnetic spins are so weak that a very large number of atoms (usually more than a trillion) are needed to generate an image, and the best possible resolution is about three millionths of a meter (about half the diameter of a red blood cell).

In 1991, theoretical physicist John Sidles first proposed the idea of combining MRI with atomic force microscopy to image tiny biological structures. IBM physicists built the first microscope based on that approach, dubbed magnetic resonance force microscopy (MRFM), in 1993.

Since then, researchers including Degen and his IBM colleagues have improved the technique to the point where it can produce 3-D images with resolution as low as five to 10 nanometers, or billionths of a meter. (A human hair is about 80,000 nanometers thick.)

With MRFM, the sample to be examined is attached to the end of a tiny silicon cantilever (about 100 millionths of a meter long and 100 billionths of a meter wide). As a magnetic iron cobalt tip moves close to the sample, the atoms’ nuclear spins become attracted to it and generate a small force on the cantilever. The spins are then repeatedly flipped, causing the cantilever to gently sway back and forth in a synchronous motion. That displacement is measured with a laser beam to create a series of 2-D images of the sample, which are combined to generate a 3-D image.

MRFM resolution is nearly as good (within a factor of 10) of the resolution of electron microscopy, the most sensitive imaging technique that biologists use today. However, unlike electron microscopy, MRFM can image delicate samples like viruses and cells without damaging them.

New targets

Degen, who became interested in pursuing new MRI techniques after seeing an electron microscope demonstration in college, says his work could help structural biologists discover new drug targets for viruses.

“Usually if you want to find out how things work, you have to find the structure. Otherwise you don’t know how to design drugs,” he says. “You’re operating in a blind spot.”

Degen and chemistry graduate student Ye Tao are now building an MRFM microscope in the basement of MIT’s Building 2. When completed, the microscope will be one of just a handful of its kind in the world. Most of the parts are in place and functioning, but Degen and Tao still need to obtain the refrigeration unit that will cool the system to just above absolute zero. The system must be cooled to 50 millikelvins to minimize thermal vibrations, which interfere with the cantilever’s magnet-induced displacement signal.

Degen hopes to receive the refrigeration unit in late May or early June, but shipment could be delayed by an ongoing shortage of helium isotopes, which are required to achieve the necessary cooling. If all goes according to plan, the microscope could be generating images by the end of this year.

Degen and two of his students are also pursuing another new approach to nanoscale MRI. This approach uses fluorescence instead of magnetism to image samples. Their new microscope replaces the magnetic tip with a diamond that has a defect in its crystal structure. The defect, known as a nitrogen-vacancy defect, functions as a sensor because its fluorescence intensity is altered by interactions with magnetic spins. This setup does not have to be cooled, so samples can be imaged at room temperature.