MIT tissue engineers have successfully healed airway injuries in rabbits using a technique they believe could apply to the trachea and other parts of the human body.

The work, published in the advance online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of May 5, expands researchers' understanding of the control of tissue repair and could lead to new treatments for tracheal injuries, such as smoke inhalation and damage from long-term intubation.

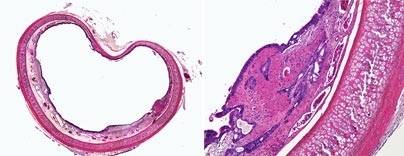

The new technique heals airway injuries by placing new tracheal cells around the injury site. Two types of tracheal cells, embedded within a three-dimensional gelatin scaffold, take over the functions of the damaged tissue.

"We can begin to replicate the regulatory role cells play within tissues by creating engineered constructs with more than one cell type," said Elazer Edelman, the Thomas D. and Virginia W. Cabot Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and senior author of the paper.

Patents on the technique have been licensed to Pervasis, a company co-founded by Edelman, which develops cell-based therapies that induce repair and regeneration in a wide array of tissues.

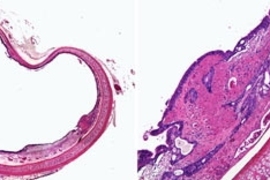

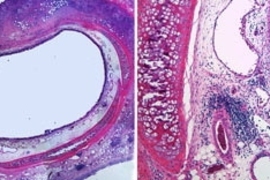

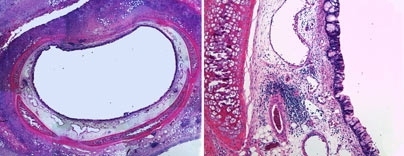

The trachea and other respiratory tubes, like most tubes in the body, have an intricate, three-layer architecture. The inner layer, or epithelium, interacts with whatever is flowing through the tube; in the case of the trachea, air. The middle layer is composed of muscle that constricts or relaxes the tube, and the outer layer consists of connective tissue that supports microvessels and small nerves.

Most attempts at tissue regeneration seek to rebuild this complex architecture with structural precision.

However, the MIT researchers found that it is not necessary to recapture the ordered layering to heal injuries. Instead, they concentrated on restoring cellular health. When cells are intact and have regained their biological function, they need only reside near the injured tissue to enhance overall repair.

Edelman and colleagues achieved this repair state by delivering a mixture of new healthy cells derived from the epithelial lining and the nourishing blood vessels. The combination of epithelial and endothelial cells take over the biochemical role lost with cell damage. The healthy cells release growth factors and other molecules necessary for healing tissue, and can modulate their delivery in response to physiological feedback control signals.

"Cells are not just an array of bricks surrounded by mortar, nor are they passive drug pumps. Cells are active elements that respond to the dynamic changes of their environment with modulated secretion of critical factors. They don't need to be stacked in one specific fashion to function, but they do need to be healthy and near the injured tissue," said Edelman, who is also a professor at Harvard Medical School and cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

To get the best results, both epithelial and endothelial cells must be replaced in the injured airway. "One cell type can't do it alone. With this complex disease, each regulatory cell offers something unique and together they optimize repair," Edelman said.

The cells must also be grown within a 3D scaffold, otherwise, the two types of cells will stay segregated and will not work as effectively.

Because of the similarities between the trachea and other tubes in the body, such as those of the vascular, genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems, the researchers believe their approach could translate to other organs.

"We can apply this same approach to so many different parts of the body," said Brett Zani, a postdoctoral associate in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology and lead author of the paper.

Other authors are Koji Kojima and Charles Vacanti of the Laboratory of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 7, 2008 (download PDF).