College courses focused on energy have been proliferating widely in recent years, at MIT and elsewhere. But one new class here approaches the subject in a very different way.

Energy has typically been taught from the perspective of mechanical or electrical engineering, materials science, chemistry, or even biology. But MIT's new "Physics of Energy" (8.21) tackles the subject in terms of the basic underlying mechanisms involved, and both the promise and the limitations that are inherent in energy alternatives based on known physical principles.

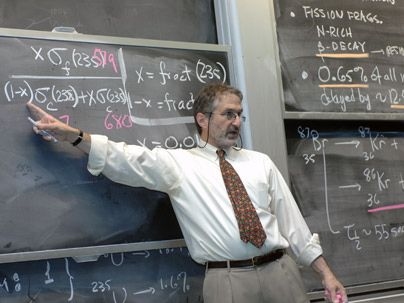

"The laws of thermodynamics, and basic physics, draw lines around what you can and can't do" in terms of harnessing various sources of energy, says Robert L. Jaffe, the Otto (1939) and Jane Morningstar Professor of Science in the Department of Physics, who co-teaches the new class with Professor of Physics Washington Taylor. The class, offered this fall for the first time, examines these fundamental constraints, and aims to give students the tools to carry out such analyses on their own, Taylor and Jaffe say.

In their online description of the course, they point out what really sets this one apart: "You may have heard about courses on the 'Physics of Energy' offered at other universities. The ones we know of are aimed at nonscientists without a background in calculus or calculus-based physics. Because MIT undergraduates are so well prepared in mathematics and physics, we will present material at a considerably more advanced level. This should make the course more exciting (and more challenging)."

At the same time, Taylor says the course is designed to be appropriate for "any undergraduate who has taken freshman physics." Jaffe adds that the class will have "the kind of intensity usually associated with physics classes."

MIT Energy Initiative Director Ernest J. Moniz says Jaffe and Taylor's approach is different from typical energy courses in its sophistication in presenting the basic, underlying science.

"As far as we know, it's unlike anything being offered elsewhere, and we hope it will provide a very useful grounding for students seeking a strong foundation in energy science, technology and policy," says Moniz, the Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor of Physics and Engineering Systems.

The motivation for creating the class, Jaffe says, came from his and Taylor's perception of the kinds of misunderstandings and misinformation that tend to surround many discussions of energy alternatives -- "things that catch your attention as a physicist, sort of like fingernails scraping on a blackboard."

For example, he says, in talking about the potential of future fusion powerplants, advocates often say the fuel supply is unlimited because there's an "unlimited amount of hydrogen in the ocean." That's true enough, but no fusion reactor would actually use ordinary hydrogen. "They use tritium," a relatively unstable radioactive form of hydrogen that is "made by bombarding lithium with neutrons. So that future is dictated by the availability of lithium, and the feasibility of manufacturing fuel in this complex way."

In this class, "we hope to give people a foundation so they won't be easily deceived," Jaffe says. They plan to present the basic science and calculations underlying issues such as the relative efficiency of different engine designs, and the effectiveness and potential of technologies such as solar thermal power and wind power.

The class will spend roughly a third of the semester each on three basic areas: first, the uses of energy, looking at various kinds of machines and engines and electromagnetic systems; second, the sources of energy, including fossil fuels, nuclear fission and fusion, and the whole range of renewables -- wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower, and so on; and third, the role of conservation and efficiency.

Two other new courses on energy are being taught here this fall as well. One is "Fundamentals of Photovoltaics," a graduate class in mechanical engineering taught by Professor Tonio Buonassisi, the SMA Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Manufacturing, which will cover everything from the efficiency of different PV materials to manufacturing and life-cycle analysis. The other is "Enabling an Energy Efficient Society," taught by Harvey Michaels, a research scientist in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on October 22, 2008 (download PDF).