The pint-sized model car sitting on a classroom table in Building E13 encapsulates the title of the four-part IAP seminar held in January: "Hydrogen: Hype or Hope?"

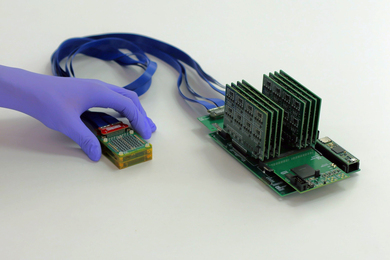

The model car, built from a kit by the seminar presenters, MIT postdoctoral associates Caetano Rodrigues Miranda and Francesca Baletto, runs on hydrogen and represents the promise of a hydrogen-based economy, with its lure of pollution-free, renewable energy.

On the other hand, the car will run maybe five minutes at a time. The days of a hydrogen-powered automobile that will rival today's gas-guzzlers are years in the future.

Yet, whether we like it or not, hydrogen may prove to be a boon to an energy-starved world, because, as Miranda and Baletto's seminar made clear, "the end of oil is coming soon." Crude oil, which supplies 37.7 percent of the world's energy, has only about 41 years of reserves left. Natural gas (19.5 percent) has 63 years of reserves and coal (21.4 percent) has 218, according to the pair.

Miranda is studying material for hydrogen storage and amorphous systems for photovoltaic applications in the group of Gerbrand Ceder, professor of materials science and engineering; Baletto is looking at key processes in catalysis, energy storage and environmentally hazardous chemical reactions in the Quasiamore research group of Nicola Marzari, associate professor of computational materials science. Together, they explored the technical challenges of a hydrogen economy, which include hydrogen production, fuel cell design, storage, distribution and transportation.

The pair provided a glimpse of a tantalizing vision of the future, with a short film on the H2PIA project, a planned community in Denmark where citizens produce and store their own hydrogen fuel, running homes and cars on renewable, pollution-free energy. "It is possible to transform this into reality," Miranda said.

However, Baletto noted, the very first step of a hydrogen economy--obtaining hydrogen--requires energy that has to be "clean." While hydrogen is plentiful in the form of water, the process of hydrolysis--which separates the hydrogen from oxygen--is currently done with gas- and coal-powered processes that produce carbon dioxide and other pollutants. For hydrogen energy to be "clean," hydrolysis must run on renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind power. It's "green hydrogen versus black hydrogen," she explained.

The model car, for example, uses a solar panel to separate hydrogen from oxygen.

Also, while hydrogen power does not produce carbon dioxide--the chief culprit in global warming--as a byproduct, it does produce water vapor which, Miranda noted, is also a greenhouse gas.

Other design challenges for a hydrogen economy include:

• Storage issues: Liquefied hydrogen has lower energy density per volume than gasoline. "Huge storage tanks are needed for very small cars," Baletto said.

• Fuel cells: Hydrogen fuel cells, while efficient, nonpolluting and silent, are complex to operate, expensive and have low durability, said Miranda.

• Storage of hydrogen in a solid form: This requires material that is strong enough to capture hydrogen atoms but weak enough to release the hydrogen when energy is needed.

A hydrogen economy would require massive changes in infrastructure, including the creation of hydrogen filling stations. Refueling a hydrogen car may take up to an hour--not an attractive option for today's drivers.

Thus, is hydrogen more hype than hope?

Miranda is optimistic--he tends to favor a "Hollywood ending," as he put it. His native Brazil, he noted, has been able to switch to more use of ethanol instead of gasoline after the government heavily subsidized ethanol's use and distribution. Now it's a free market. Hydrogen is "the best candidate for replacing oil in the long term," he said.

Baletto, however, opts for a more "European movie ending," in which obstacles take much longer to sort out and problems remain. "Hydrogen is a possibility we have to explore. In any case, we have to start to change the way to produce energy."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 7, 2007 (download PDF).