It was perhaps the most famous act of artistic destruction in modern history. After renowned Mexican artist Diego Rivera refused to alter a mural commissioned for the Rockefeller Center in New York City, the painter was sent packing and the 1933 mural demolished.

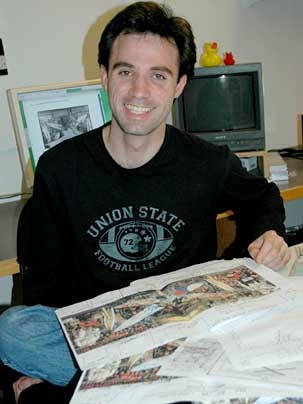

Ben Wood, a second-year graduate student in visual arts in the Department of Architecture, has long been fascinated by murals. He became intrigued with the controversy over Rivera's original commission and the copy the artist later painted in the Palacio De Bellas Artes Museum in Mexico City.

The controversy of Rivera's mural has been depicted in two recent films, "Frida" and "The Cradle Will Rock." It is well known that Rivera's design included a portrait of Lenin among the many figures; that when the press complained about it, Rivera insisted on making Lenin's figure even more prominent; and that Rivera was fired.

Wood is interested in the known and the less-known aspects of the Rivera mural tale. His research is devoted to bringing the story and the artwork to light, seeking to answer what Rivera's elaborate vision--grandiosely titled "Man at the Crossroads"--might mean to us today. Wood wondered: What is the significance of Rivera's 1934 version, even more grandiosely called "Man in Control of the Universe"? Can man ever really be in control of his destiny?

So for his MIT thesis project, Wood put together "a contemporary re-creation of Rivera's mural to consider what it means today." And now Wood has been asked to return to Mexico to create a version of his project during events marking the 50th anniversary of Rivera's death.

Wood, a native of Brighton, England, has worked on a mural project before. In 2004 he photographed a mural, completed in 1791 by Native Americans, which had been hidden for more than 200 years behind an altar in San Francisco's Mission Dolores.

Wood started working on the Rivera project in 2006; he conceived of it as a proposal to the Rockefeller Center to re-create the mural there. It didn't get accepted by the center, but "they didn't shut me down completely," he said. "I'm going to propose it again next year."

In his research in the Rockefeller Center archives, Wood obtained Rivera's original proposal for the mural, in which the artist described how man, represented as a skilled worker in the center of the mural, "looks with uncertainty but hope toward the future." He did numerous interviews here and in Mexico. He went to California to interview one of Diego's assistants and he traveled to Mexico to interview two of Diego's grandsons and his daughter. He talked to MIT's Noam Chomsky and to his own advisor, Krzysztof Wodiczko, MIT professor of visual arts. Wood's aim was to understand why the mural was destroyed, what the mural means, and what its implications might be for today.

Then, with computer technology and using an image of the 1934 mural, he made the mural "speak"; the painted figures come to life and morph into the faces of people interviewed by Wood. On May 18, Wood presented his thesis as a 17-minute video, projected on a wall at MIT.

Now Wood has a chance to take his project to Mexico. He is working with the National Museum of Art in Mexico City to create a project on Rivera's mural at the museum to mark the 50th anniversary of Rivera's death in November. He will either present a version of his thesis project--with the interviewees speaking in Spanish--or he will recreate the mural in an entirely new way, seeking people to interview to represent the themes of the work.

Rivera's own politics, his experience at the intersection of the Rockefeller family, their business interests and the political winds that blew through America during the Depression, Wood acknowledged, affected the mural's fate.

But Wood seeks to probe more deeply the context of why the mural was destroyed. "I think it's too simple to say it was the head of Lenin that was the reason for its destruction."

Wood also examines Rivera's utopian vision: how, for example, he depicted the man at the crossroads as a white Anglo Saxon. Wood is keenly interested in what is "wrong" with the mural, that is, what is there and what is not there.

Rivera's vision might even be considered "totalitarian," that is, "he is trying to present this vision of the future, the different elements that will allow a more ethical future, an ideal world. But at the same time the elements in there are prohibiting us, because they are his vision of a better world." Those elements included Rivera's vision of the growth of Communism in the capitalist, multicultural society of the United States, Wood said.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on June 13, 2007 (download PDF).