Researchers at MIT and Harvard Medical School have identified a compound that interferes with the pathogenic effects of Huntington's disease, a discovery that could lead to development of a new treatment for the disease.

There is no cure for Huntington's, a neurodegenerative disorder that now afflicts 30,000 Americans, with another 150,000 at risk. The fatal disease, which is genetically inherited, usually strikes in midlife and causes uncontrolled movements, loss of cognitive function and emotional disturbance.

"There are now some drugs that can help with the symptoms, but we can't stop the course of the disease or its onset," said Ruth Bodner, lead author on a paper that appears this week in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and which will appear in the print edition March 14. Bodner is a postdoctoral fellow in MIT's Center for Cancer Research.

The compound developed by Bodner and others in the laboratories of MIT Professor of Biology David Housman, Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor Aleksey Kazantsev and Harvard Medical School Professor Bradley Hyman might lead to a drug that could help stop the deadly sequence of cellular events that Huntington's unleashes.

"Depending on its target, any one compound will probably block only a subset of the pathogenic effects," Bodner said.

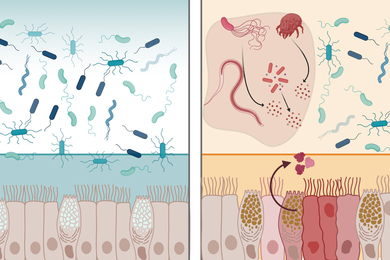

Huntington's disease is caused by misfolded proteins, called huntingtin proteins, that aggregate and eventually form large clump-like "inclusions." The disease is characterized by degeneration in the striatum, an area associated with motor and learning functions, and the cortex. The proteins may disrupt the function of cellular structures known as proteasomes, which perform a "trash can" function for the cell -- disposing of cellular proteins that are misfolded or no longer needed, said Bodner.

Without a functional proteasome, those cellular proteins accumulate, poisoning brain cells and impairing patients' motor and cognitive function.

Until now, most researchers looking for Huntington's treatments have focused on compounds that prevent or reverse the aggregation of huntingtin proteins. However, recent evidence suggests that the largest inclusions may not necessarily be harmful and could in fact be protective, said Bodner. So, the MIT and Harvard scientists decided to look for compounds that actually promote the formation of large inclusions.

The highest concentration of protein inclusions was found when the researchers applied a compound they called B2 to cells cultivated in the laboratory. The compound also had a strong protective effect against proteasome disruption, thus blocking one of the toxic effects of the huntingtin protein.

The B2 compound also promoted large inclusions and showed a protective effect in a cellular model of Parkinson's disease, another neurodegenerative disorder caused by misfolded proteins.

In Parkinson's disease, the mutant proteins destroy dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra. Normally, the dopamine transmits signals to the corpus striatum, allowing muscles to make smooth, controlled movements. When those dopamine-producing cells die, Parkinson's patients exhibit the tremors that are characteristic of the disease.

The researchers are now working on finding a more potent version of the compound that could be tested in mice.

This work was funded by the Hereditary Disease Foundation, Massachusetts Biotechnology Research Council, National Institutes of Health, American Parkinson's Disease Association and the MassGeneral Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 8, 2006 (download PDF).