The evolutionary split between humans and chimpanzees is much more recent -- and more complicated -- than previously thought, according to a new study by scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and colleagues.

The work was published in the May 17 online edition of Nature.

The results show that the two species split no more than 6.3 million years ago and probably less than 5.4 million years ago. This is about 1 million to 2 million years more recent than previous estimates. Moreover, the time from the beginning to the completion of divergence between the two species ranges over more than 4 million years. This range is much larger than expected.

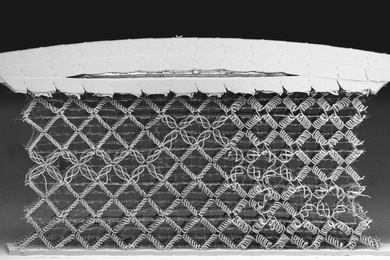

The study also showed that the X chromosome is on average 1.2 million years "younger" than the 22 autosomal (non-sex) chromosomes. This indicates that the separation of the two species, or speciation, was unusual -- possibly involving an initial split followed by later interbreeding before a final separation.

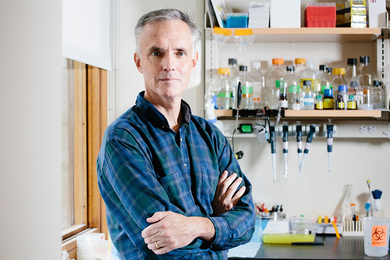

"The genome analysis revealed big surprises, with major implications for human evolution," said Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute, co-author of the Nature paper and an MIT biology professor. "First, human-chimp speciation occurred more recently than previous estimates. Second, the speciation itself occurred in an unusual manner that left a striking impact across chromosome X. The young age of chromosome X is an evolutionary 'smoking gun.'"

Previous molecular genetic studies have focused on the average genetic difference between human and chimpanzee. By contrast, the new study exploits the information in the complete genome sequence to reveal the variation in evolutionary history across the human genome.

The previous estimate that humans and chimpanzees split 6.5 million to 7.4 million years ago is based on the famous Toumaï hominid fossil, which has features thought to be distinctive to the human lineage.

"It is possible that the Toumaï fossil is more recent than previously thought," said Nick Patterson, a senior research scientist and statistician at the Broad Institute and first author of the Nature paper. "But if the dating is correct, the Toumaï fossil would precede the human-chimp split. The fact that it has humanlike features suggest that human-chimp speciation may have occurred over a long period with episodes of hybridization between the emerging species."

The possibility of "hybridization" -- that is, initial separation of the two species, followed by interbreeding and then final separation -- would also explain the strange phenomenon seen on chromosome X. Interbreeding is known to place strong selective pressures on sex chromosomes, which could translate to a very young age for chromosome X.

Hybridization is commonly observed to play a role in speciation in plants, but evolutionary biologists do not generally view it as an important way to produce a new animal species.

"A hybridization event between human and chimpanzee ancestors could help explain both the wide range of divergence times seen across our genomes, as well as the relatively similar X chromosomes," said David Reich, senior author of the Nature paper, an associate member of the Broad Institute and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School's Department of Genetics.

"That such evolutionary events have not been seen more often in animal species may simply be due to the fact that we have not been looking for them," he said.

As the researchers note in the Nature paper, it should be possible to refine the timeline of speciation and test the possible explanations based on complete genome sequencing of the gorilla and other primates, which is already under way at several centers, including the Broad Institute.

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute and Burroughs-Wellcome.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 24, 2006 (download PDF).