Researchers led by an MIT graduate student have discovered a bacterium that is a magnetic misfit of sorts.

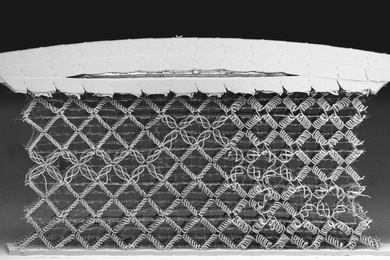

Magnetotactic bacteria contain chains of magnetic iron minerals that allow them to orient in the Earth's magnetic field, like living compass needles. These bacteria have long been observed to respond to high oxygen levels in the lab by swimming toward geomagnetic north in the Northern Hemisphere and geomagnetic south in the Southern Hemisphere.

But now researchers from MIT, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Iowa State University have found a bacterium in New England that does just the opposite: a Northern Hemisphere creature that swims south.

Because this behavior doesn't make sense in the natural environment of the bacteria, where swimming south would take them away from areas with their preferred oxygen level, the researchers believe there must be other explanations for why some magnetotactic bacteria swim in particular directions.

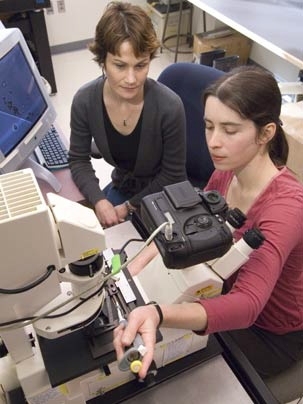

The team dubbed the bacterium the barbell for its appearance. In a study reported in the Jan. 20 issue of Science, they describe how they used genetic sequencing and other laboratory techniques to identify the barbell, which was found coexisting with other previously described magnetotactic bacteria in Salt Pond on Cape Cod.

Magnetotactic bacteria are found throughout the world in chemically stratified marine and freshwater environments, said lead author Sheri Simmons, a graduate student in the MIT Department of Biology and the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography and Applied Ocean Science and Engineering.

The coexistence of magnetotactic bacteria with north and south polarity in the same environment contradicts the currently accepted model of magnetotaxis, which says that all magnetotactic bacteria in the Northern Hemisphere swim north and downward to reach their desired habitat when exposed to high-oxygen conditions.

Simmons and colleagues studied the bacteria under laboratory conditions and say the behavior of the bacteria in situ could be different from laboratory behavior. Their results, however, suggest new models are needed to explain how these magnetotactic bacteria behave in the environment.

This work was supported by the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute, Ocean Life Institute and Ocean Ventures Fund, as well as the National Science Foundation and a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 1, 2006 (download PDF).