Technology being developed at MIT promises to pave the way for the next generation of wireless networks, saving consumers hundreds of billions of dollars over the next 20 years.

Wireless companies are investing big in new infrastructure that can handle the ever-increasing demand for inexpensive delivery of voice and data. But the solid-state amplifiers that the nation's roughly 200,000 wireless base stations now use to communicate with cell phones and other electronic devices are costly, generate excessive heat (requiring bulky cooling equipment) and need large backup batteries.

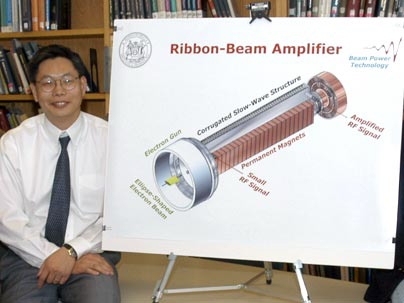

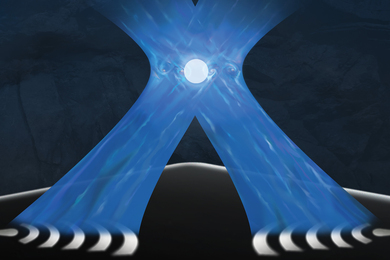

MIT researchers are developing an alternative: the first radio frequency (RF) power amplifier based on a ribbon-beam vacuum electron device. The new amplifier combines a half-century-old technology-vacuum electron devices, or "vacuum tubes" in the old terminology-with a recent MIT breakthrough: an elliptical, or "ribbon," electron beam.

A ribbon electron beam is much more efficient for RF amplification than the one-dimensional, pencil-like electron beam that conventional vacuum electron devices emit. A ribbon-beam vacuum electron device requires less energy than either conventional vacuum electron devices or the solid-state transistors that replaced them in many applications decades ago.

In January, Chiping Chen, principal research scientist in the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center, and his colleagues published a paper for the American Physical Society on the first-ever successful demonstration of a ribbon electron beam.

Ronak Bhatt, a physics graduate student involved in the project, received a best-student-paper prize at the Particle Accelerator Conference in Knoxville, Tenn., this spring for a paper describing how a ribbon beam is generated.

To build the amplifier, the team also invented a ribbon-beam focusing system and a coupling device between the beam and the RF signal.

"This technology could change how radio-frequency amplifiers are made," said Chen.

Ribbon beam amplifiers (RBAs) are smaller, generate less heat, require smaller backup batteries, are more electrically efficient and cost thousands of dollars less than solid-state amplifiers. And because they could be mounted directly on a base-station tower, less signal decay would occur during transmission.

These new amplifiers would enable the completion of next-generation wireless networks by dramatically improving throughput and reducing the cost of base stations by 65 percent. Chen believes RBAs have the potential to reduce the cost of delivering voice and data from the current 50 cents per megabyte to five cents per megabyte.

Moreover, their high power and their capacity to operate at low and high frequencies (from 1.9 GHz for third-generation U.S. wireless base stations to 5.8 GHz for WiMAX, or wireless broadband networks) make them "future-proof" for successive generations of wireless networks.

Wireless and power-amplifier companies such as Ericsson, Nokia, Motorola, Andrew and PowerWave have expressed interest in RBA technology and are willing to test prototypes, said Chen. He expects that the first RBA will be on the market in two years.

RBAs are a broad-platform technology with a range of applications in not only communication (telephony, WiMAX, satellite communications), but also defense (radar, missile defense) and scientific research (particle acceleration).

This work is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and the MIT Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation.