As a fiber, spider silk is so desirable that scientists have spent decades trying to find a way to mimic it. A team at MIT has been tackling the problem from two directions.

"The main goal is to be able to reproduce the enormous energy absorption and strength-bearing properties of spider silk," said Paula T. Hammond, an associate professor in MIT's Department of Chemical Engineering. "[We want] to be able to obtain a material in large quantities and cheaply ... without DNA techniques, which are expensive."

Hammond's graduate students Greg Pollock and LaShanda James-Korley presented papers on the research at the national meeting of the American Chemical Society on March 23-27. The work is part of a collaborative effort between Hammond and Professor Gareth McKinley of the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

The focus of the work is on creating materials that could create the high-strength fibers needed for artificial tendons, specialty textiles and lightweight bullet-proof gear. A light, tough material like spider silk would be ideal. But unlike sheep or silkworms, spiders cannot be penned in together or raised as a group, making them difficult to domesticate. "They're territorial and cannibalistic," explained Pollock. Hence scientists' interest in producing artificial fibers with similar properties to spider silk.

Spider silk is known to be a polymer with two distinct alternating regions. One region is soft and elastic; the other forms small, hard crystallites. It is assumed that this unusual structure is largely responsible for spider silk's remarkable properties.

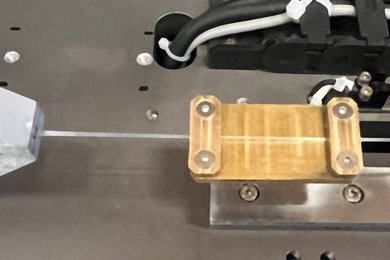

MIT researchers want to make a series of different synthetic polymers and study how changes in the chemical structures of the polymers affect the physical properties. This research is done in parallel with research focusing on processing techniques that will maintain the unusual properties of the materials produced.

Scientists at Nexia, a small startup company, have been able to harvest spider silk from the milk of genetically altered goats, but as Pollock explained, that type of solution does not solve the problem entirely. "It's some fabulous work," he said, but "no one has really figured out what nature's done and why it works.

"We're trying to understand the structure-property relationships by creating our own material with a mechanism for toughness, and seeing [if] the structural units produce toughness the same way the amino acids in spider silk produce toughness," he continued.

James-Korley's work focuses on the soft segment of spider silk. It has been suggested that this soft part has two different regions, one of which is slightly harder than the other because the polymer fibers are partially aligned. If this idea is correct, spider silk actually has three different phases: hard, soft and intermediate. The hard segments anchor the partially aligned regions, holding them in place in a matrix of soft material.

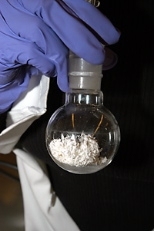

James-Korley has been trying to produce materials with such a structure to test this hypothesis. She has been studying soft-segment polymers made with two different types of materials, hoping that the two materials will form separate phases, the way oil and water do when mixed. When her two-phased soft segments are combined with a hard segment, she will have a three-phase material that she hopes can imitate some of the properties of spider silk.

Pollock is studying a different structural element--the interface between the crystallites in spider silk and the soft region around them. How the interfacial material slides past the crystallites without pulling away from them may hold the key to spider silk's toughness.

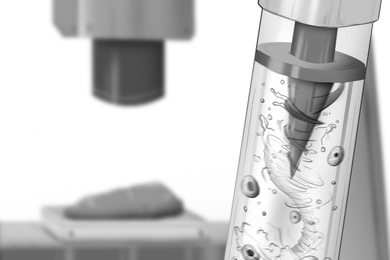

James-Korley and Pollock's work is part of a larger collaborative effort, which includes a new spinning process that may help create durable fibers from their polymeric materials. This process, called resin-spinning, was developed in the McKinley lab and is being studied in detail by graduate student Nikola Kojic.

This work is funded by the U.S. Army Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies. James-Korley is also funded by a Lucent Technologies Cooperative Fellowship.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 7, 2003.