Two MIT Nobel Prize-winning scientists outlined the potential impact of recent security measures on education and on scientific progress in lectures on Sept. 23 in Kresge Auditorium.

Institute Professors Jerome I. Friedman, who won the Nobel Prize in phsyics in 1990, and Phillip A. Sharp, a 1993 Nobelist in physiology or medicine and director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, spoke on "Defining the Boundaries: Homeland Security and its Impact on Scientific Research," the sixth Ford/MIT Nobel Laureate Lecture.

"The well-being of the nation will suffer if the exchange of ideas in science is threatened. Overzealous efforts to protect the nation actually weaken it," Friedman said.

Friedman commented on the differences between classified research conducted on behalf of national security during World War II and research conducted at universities today. He cited early secret work on the Manhattan Project conducted at the University of Chicago, and research on radar at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT. In those secure facilities, all work was classified as secret, he said.

"During World War II, it was easy to distinguish research on fissionable materials from other things. During the war, research on uranium was classified. Such clear separations aren't so easy with biological research," he said.

Friedman emphasized MIT's commitment to public service and to helping the nation as it did during the war through classified research.

"Such help is and should be conducted in secure facilities like Lincoln Lab," he said.

MIT's decision to have no classified research conducted on its campus reflected concern for the vitality of science and for the well-being of its students.

"If you try to restrict the communication of research results, science does not progress," he said.

Also, if graduate students work on classified projects, they are shut out of review by the general scientific community. They aren't able to discuss their work with potential employers. And it is divisive when some students, faculty or staff have security clearances; it creates two classes of people on campus, Friedman said.

"We concluded the free flow of information was the best way for MIT to serve the public interest. An environment of free and open communication, with peer reviews, open sharing and debate, insures continued progress. Openness attracts the best students," Friedman said.

In a concrete and sometimes moving way, Sharp illuminated the dangers of focusing narrowly on bioterrorism.

"Nature has created better diseases than we could design--smallpox, polio, Ebola, malaria. The biological community worries about the reemergence of a 1919 pandemic flu. Infection by known, natural pathogens is a much bigger threat than bioterrorism.

"Consider HIV, discovered recently. Over the past 20 years, 20 million have died and 40 million are affected. That's a greater death toll than any biological weapon," Sharp said.

History has already featured the scenario now haunting biologists and others. "The most damaging example of biological warfare was the transfer of diseases such as smallpox from Europe to the indigenous people of the New World," he said.

"We must preserve public health and research policies that do no harm. There is no such thing as complete protection. Expanding funding for more research into known pathogens means we'll all be more safe," Sharp said. He recommended updating the small pox vaccine, now 50 years old, and developing and delivering new vaccines.

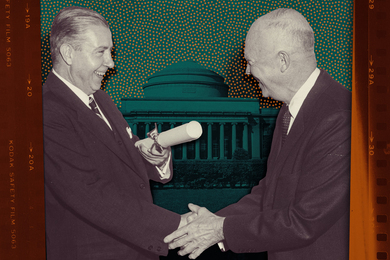

President Charles M. Vest, who served as moderator, sketched developments in national security policies over the past two years.

"Balance is possible between the need to keep the nation and the world secure and basic American values of openness," he said.

"Openness is one of MIT's greatest strengths."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on October 1, 2003.