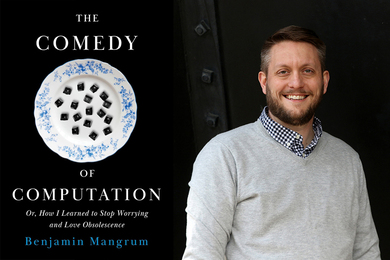

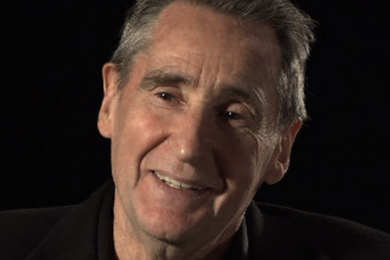

Professor of Biology Rudolf Jaenisch took an active role last week in standing up for responsible science and being a spokesperson against embarking on human cloning.

In media interviews, a testimony to a House subcommittee and an editorial in Science magazine, Professor Jaenisch told the public, Congress and scientists that we are not ready to clone humans.

"The successes in animal cloning have led some to suggest that the technology can now be applied to humans. Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, all research to date suggests that cloning is inefficient and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future," said Professor Jaenisch, a Whitehead Institute researcher.

The hearing by the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations was called after two groups announced plans to clone a human being.

To date, five mammalian species (sheep, mice, goats, cows and pigs) have been cloned, and the great majority of all clones (of all five species) died either at various stages of embryonic development, at birth or soon after birth, with a variety of malformations. Many newborn clones are overweight and have an increased and dysfunctional placenta.

Those that survive the immediate perinatal period may die within days or weeks after birth with defects such as kidney or brain abnormalities, or with a defective immune system. Even apparently healthy adult clones may have subtle defects that cannot be recognized in the animal.

"Given the failure rate, it would be dangerous and irresponsible to attempt human cloning. The risks to the fetus and the developing child are unacceptable. If human cloning is attempted, those embryos that do not die early may live to become abnormal children and adults. Both are troubling outcomes," said Professor Jaenisch.

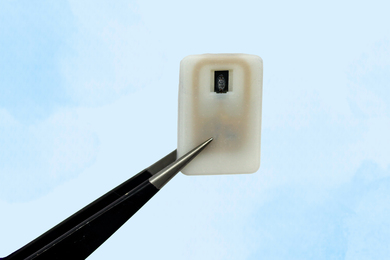

He explained that the most likely cause of abnormal clone development is faulty reprogramming of the genome. This may lead to abnormal gene expression of any of the 30,000 genes residing in the animal. Faulty reprogramming does not lead to chromosomal or genetic alterations of the genome, so methods that are used in routine prenatal screening to detect chromosomal or genetic abnormalities in a fetus cannot detect these reprogramming errors. There are no methods available now or in the foreseeable future to assess whether the genome of a cloned embryo has been correctly reprogrammed.

"The experience with animal cloning allows us to predict with a high degree of confidence that few cloned humans will survive to birth, and of those, the majority will be abnormal," Professor Jaenisch said.

The cloning controversy was stirred last month when an international group of fertility experts announced it would begin the world's first concerted effort to clone a human being. The team, including Kentucky fertility expert Panos Zavos and an Italian collague, obstetrician Severino Antinori, met in Rome to work on their plan and declared that they would attempt to clone a human within a year.

Most cloning experts agree that it would be too dangerous to attempt human cloning.

Professor Jaenisch became an spokesperson in taking this message to the public. In interviews with several newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post, the New York Times and the Boston Globe, as well as in TV interviews with CNN, ABC, CBS, WGBH and Fox, Professor Jaenisch clearly laid out the issues that made attempting human cloning irresponsible and dangerous.

"Every success in animal cloning has been accompanied by an enormous number of failures," he said. "For every animal that has been cloned, there have been hundreds of others that have failed. They either died during embryonic development or soon after birth, most with fatal defects of the heart, lung, kidneys or the immune system." Given this knowledge, how can we justify cloning humans, he asked.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on April 4, 2001.