Editor's Note: The page turner prototype described in this article is used to teach the mechanical design process. Unfortunately, it is NOT available for purchase, and we are unable to respond to inquiries on this subject or provide any further information.

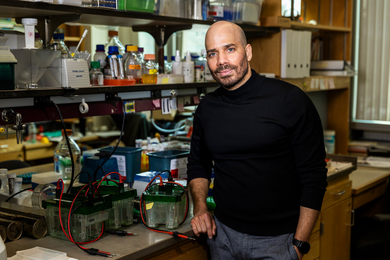

An MIT inventor recently built a device that matches the futuristic requirements of George Jetson with the technological know-how of Leonardo da Vinci. Ernesto Blanco designed a page turner that automatically turns the pages of a book without the reader lifting a finger.

The device was created at the request of musicians, who don't always have a free hand for turning the pages of their music while they're playing. But it could also prove useful for people with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease or other medical conditions.

The high-tech gadget offers an improvement on a very low-tech medium: printed books.

"The technology I'm using here was available to Leonardo da Vinci in 1490; we're 500 years behind in inventing this," said Adjunct Professor Ernesto Blanco of mechanical engineering, who invented his first page turner in response to a request from his violin-playing niece, his second in response to a pianist friend, and the third for an exhibit at MIT's List Visual Arts Center. He's currently working on a fourth.

"There are a few page turners on the market already, but they're very expensive and very unreliable," said Professor Blanco. "This one cost only about $150 to make. And it works."

The device utilizes a mechanical arm with a small spool of sticky tape that lifts each page and turns it. The musician or reader can operate it with the push of a button, or set a timer. Professor Blanco built the prototypes himself using molded plastic and circuitry; only the small motor and the batteries were off-the-shelf items.

He built the first one about 23 years ago.

"My niece asked if I could build one for her. I said 'Yes, it should be very easy.' I went to work and found it wasn't so easy. So I told her that I was very, very busy right then," said Professor Blanco, who explained that his difficulty was in designing a system that would work on any size page of any weight of paper. After a couple of weeks, he became frustrated.

"I stood up in front of the machine and said, 'Why can't I do this? Am I not good enough?' I've found that when you reach the point where you begin to wonder whether it can be done, you become very, very creative. Unfortunately, that's when most people give up. Instead, you should try something -- anything -- whether it's logical or not so logical," he said.

Professor Blanco teaches engineering design courses at MIT and uses the page turner as a case study on the design process. Part of its beauty is that it has an inexpensive design using basic mechanics, but demanded ingenuity to come up with a workable solution.

For instance, in this case suction wouldn't work as the mechanism for lifting pages, because paper is porous. And sticky tape, which works well now, proved difficult at first; once it stuck to the paper, the page wouldn't fall off. Professor Blanco finally realized the paper would fall off when the tape was rolled, and thus hit upon the answer: a spool of sticky tape that rolls a bit and strips off easily.

"After I came up with the answer, I thought, 'Why didn't I think of this before?' Then I consoled myself with the thought that no one else had thought of it either," he said.

Professor Blanco said he hasn't marketed any of his page turners yet because a market study done at Sloan revealed discouraging prospects.

"If market research had been done on the airplane, would anyone have put the money into its development? How can anyone determine the importance of something unknown to society through a marketing study?" asked Professor Blanco, who holds 14 patents and has filed for another for the most recent page turner. Most of his patents are on medical devices. One patent is for Flip-it, an automatic pancake-flipper currently being made in China that will be marketed in the United States.

The sticky-tape page turner was designed at the request of Jennifer Riddell, assistant curator at the List Visual Arts Center, who needed it for an art exhibit last fall.

Lewis de Soto's Recital revolved around a book called An Atlas of the Brain of a Pianist about a deceased pianist/composer, Chiyo Tuge, whose neurosurgeon husband dissected her brain in an effort to capture the essence of her creativity. In de Soto's exhibit, a player piano performed with the book resting on the piano in place of printed music. The page-turner automatically turned the pages every three minutes. The gallery had purchased a page turner that didn't work. It was returned after Professor Blanco agreed to supply a reliable model.

"The page turner really made the exhibit. The whole thing was very evocative and elegiac. You walked into a darkened room and heard this music and there was nobody playing it," said Ms. Riddell, who said the exhibit has now moved on to Milan, sans the page turner.

"MIT is probably one of the few places in the world where we could have found someone to engineer a page turner from scratch in the space of about two months. Meanwhile, a company whose specialty is making such products for the disabled cannot seem to get it right," Ms. Riddell said.

It's fitting that Professor Blanco's work was used for an art exhibit exploring the creative portion of the brain, something he tries to get at in his teaching. He urges his students, as well as his consulting clients, to approach problems unconventionally.

"My vocation is to show our very competent engineers that they can be creators and not just optimizers. We at MIT develop the left side of the brain, the analytical side. We're not paying enough attention to the other half of the brain, the more creative side," said Professor Blanco, who taught at MIT from 1960-64 and returned in 1977, after spending many years working full-time in industry on a wide range of innovations.