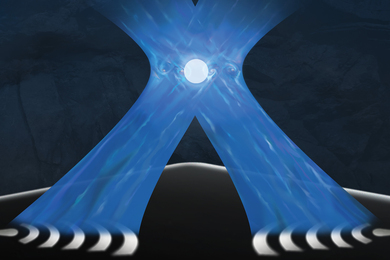

Smoke from the massive forest fires that plagued Mexico earlier this year caused three times the normal number of positively charged lightning strikes to ground in the southern plains of the United States, an MIT researcher and his colleagues reported in the October 2 issue of Science.

The smoke that migrated up the Mississippi River valley "appeared to have a substantial influence on the electrical characteristics of thunderstorms over the central United States," said Earle Williams, principal research scientist in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering's Parsons Laboratory at MIT. "In some way, the smoke from these fires significantly altered the electrical characteristics of a wide variety of storm types during all phases of their life cycles.

"Ordinarily, thunderstorms produce negative flashes to the ground," Dr. Williams said. "For two months this spring, these shifted to positive dominance, which is very bizarre." Another instance of hefty numbers of cloud-to-ground flashes of positive polarity occurred during the severe fires in Yellowstone National Park in 1988, he said.

Between April and June, nearly half a million flashes in the southern plains were positively charged. These thunderstorms also produced abnormally high numbers of mesospheric optical sprites. These fleeting red jellyfish-shaped glows are the signature of massive thunderstorms called mesoscale convective systems that occur in the wee hours of the morning in the Earth's upper atmosphere.

Smoke usually provides particles of matter on which cloud vapor condenses, leading to bigger drops of water which in turn can affect the ice-based mechanisms responsible for separating the lightning's charge, he said. But there is currently no hard-and-fast explanation for the physical mechanism behind this phenomenon, he added. "Very little is known about the microphysics of lightning."

The ominous haze of smoke and other pollutants that hovers over cities in the planetary boundary layer -- a 500-to1,000-meter band of air -- only gets cleaned out when it rains or snows. When a high amount of smoke, soot, contaminants or aerosols are in the atmosphere, they can get "ingested" by storms and affect lightning production.

It's only within the past 10 years that scientists have been able to accurately calibrate lightning characteristics, thanks to the US National Lightning Detection Network, which routinely locates all cloud-to-ground flashes in the United States to within a kilometer and identifies their polarity and timing to within a microsecond.

Positive flashes were once thought to be so rare that it was only after these routine measurements were established that scientists realized that they occurred with any regularity at all -- about 10 percent of the time.

Dr. Williams speculated that El Ni���o, which has caused the Earth's three major tropical zones to get warmer and has led to increased fires and drought in some regions, may influence the global electrical circuit by generating more positive lightning. This potentially significant impact on the global circuit would be of interest to scientists but wouldn't have any noticeable effect on the population, he said.

The research team includes Walter A. Lyons and Thomas E. Nelson at the Yucca Ridge Field Station in Fort Collins, CO, and John A. Cramer and Tommy R. Turner at Global Atmospherics in Tuscon, AZ. This research was conducted in part with support from the National Science Foundation, NASA and the US Department of Energy.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on October 7, 1998.