A perpetual motion machine, or one that moves forever with no source of energy from the outside, is considered impossible by organizations including the American and British patent offices (the latter will not accept patent applications on this subject; the US requires a working model).

So what could be a better problem for MIT undergraduates to tackle?

Two students have won honorable mentions in MIT's first Perpetual Motion Competition. Carl C. Dietrich, a junior in aeronautics and astronautics, and David A. Shear, a sophomore in mechanical engineering, each received $250 for their written proposals describing machines they believe fit the criteria. They will receive their prizes at a reception May 14 .

Six undergraduates entered the competition. None succeeded in winning the $500 first prize by stumping the judges -- students in a class taught by Dr. Yuri B. Chernyak within the Concourse Program directed by Professor Robert M. Rose. However, the entries from Mr. Dietrich and Mr. Shear were so well done that the judges agreed they merited some acknowledgment and split the money between them.

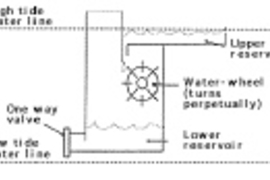

Mr. Dietrich submitted his entry, which presented three machine designs, "on the premise that this design competition is not some form of elaborate April Fool's Day joke." (The deadline for entries was April 1.) He went on to describe a water wheel that turns perpetually based on tidal motion, a second water wheel that employs solar energy to do the same, and a generator flying in space that uses "the flux of ions emanating from the sun" to move about.

Mr. Shear described a continuously spinning top that works via magnets inside the top and under the concave dish the top spins in. Although the judges eventually debunked this submission, too, "the model kept us busy for some time," they wrote in a letter to Mr. Shear.

Why are two MIT instructors "espousing such a major crackpot idea?" said Dr. Chernyak, a NASA senior fellow at MIT. Answer: it's a great teaching vehicle. "There's some very serious physics behind the humor," he said. "You have to understand the physics of the world to understand why a perpetual motion machine will or won't work��������������������������� The ability to find errors in some fine presentations is a vitally important feature of a scientist."

Dr. Chernyak teaches Problems in Electricity and Magnetism, a Concourse Program enrichment course for students in their second term of physics. "The problems presented are meant to stretch their minds, and give them a better intuitive feel for physics," said Professor Rose, of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

In past semesters, some of those problems led to the students' unintentionally inventing their own perpetual motion machines, some of which seemed to create energy where there was none before. The appearance of such seemingly simple solutions to global energy and environmental problems led to spirited arguments, analysis, and, according to Professor Rose, "a much deeper understanding of freshman physics��������������������������� Then it occurred to us that we should extend this challenge to the MIT community at large," and so the Perpetual Motion Competition was born.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 13, 1998.