When the stress created by seemingly endless work and study reaches its max, many seek solace in relaxing outside activities. Some of these, even the healthiest, can be habit-forming.

So it is with the MIT Hobby Shop, where for 60 years students and others have been transferring tension to wood and metal: boring, bending and torquing those materials into fine works of craftsmanship -- or semblances thereof -- and feeding the habit long after graduation.

In celebration of 60 years of temptation, the MIT Hobby Shop will hold a reception on Thursday, Oct. 29 from 4-7pm for all those who have succumbed to its lure -- faculty, students, staff, alumni/ae and spouses -- especially those still under its influence.

Hobby Shop director Ken Stone (SB 1972) got hooked as an undergraduate ("this was my favorite place; my first project was building pledge paddles for my fraternity") and came back to head the shop in 1991 when his friend and shop mentor George Pishenin retired from a 20-year stint as shopmaster. Mr. Stone, who started his own woodworking business after getting his architecture degree, was happy to be back.

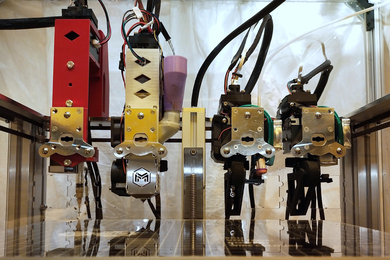

"You name it, it's been built in the Hobby Shop: electronics, model railroads, rocketry, boats and aircraft. The original transmitter for the MIT radio station was built here," he said, describing some of the rich history of the shop, which was originally located in Building 2 before moving to its present location in W31-031 in 1963.

The lore includes a photograph that Admiral Byrd sent the Hobby Shop, thanking the students for their gift of a five-foot square plaster model of the southwestern Pacific Islands, with accurate curvature of the Earth.

Another notable project was by Chuck Jordan (SB 1949), who recently wrote a letter to Mr. Stone honoring the shop's 60th. "I am forever grateful for the MIT Hobby Shop. My time spent in the Hobby Shop was a great relief from the mental exercises at MIT -- and as it turned out, had a profound influence on the rest of my life," he wrote.

As a sophomore in 1947, Mr. Jordan used the shop to build his idea of the "car of the future." He entered the prototype in a national contest sponsored by General Motors and took first prize, landing a $4,000 scholarship and job as an auto designer at GM.

"In 1992, I retired from General Motors as vice president in charge of design," wrote Mr. Jordan.

"In the early days," said Mr. Stone, "they spent as much time getting the machines running as they did using them. It was more of a club then. People came here to socialize as well as work. They even wrote a constitution that outlined how to progress from journeyman to master craftsman. In those days, you could get your own key if you were a master craftsman.

"But those days are gone. I don't give out keys any more. People join now to build something. And they expect the machines to be working. That's my job."

Besides caring for the equipment, Mr. Stone also helps Hobby Shop users plan and carry out their ideas, even toning them down when necessary.

"People come in with the idea that they're gonna build a model of the Titanic at half size," said Alex Slocum (SB 1982, SM, PhD), the Alex and Brit d'Arbeloff Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering and a shop user since his freshmen days who now serves as chair of the Hobby Shop Committee. "Ken works with them and they leave here with something on a more modest scale."

Professor Slocum's own first project was building a winch system for his truck. "I pulled myself out of many a mud hole with it," he said.

"The shop is relaxing, lowers stress and can be a positive alternative social experience. I always thought it was fun to invite date-type people to the Hobby Shop," Professor Slocum said. In fact, he and his wife, an electrical engineer, spent some time together building things before they married. "Lots of women use the shop. Sawing wood is not solely a male thing," he observed.

Dana Andrus, a senior editor at MIT Press, agrees. She took an IAP class in table-making in 1986 ("all I really meant to do then was learn enough to restore some old pieces of furniture") and wound up a Hobby Shop addict.

"Contrary to what many people might think, the Hobby Shop is not a preserve of men. Many women are active members, and this is largelydue to the generous help and expertise available from Ken Stone and Roy Talanian." (Mr. Talanian assists Mr. Stone in running the shop.)

"I ended up copying a $2,000 table I saw at Shreve's in Boston. Ever since, it's been a nonstop flow of ideas. I'll never forget George helping me duplicate a brass knob with an 18-petal chrysanthemum motif on the milling machine or Ken patiently finding a way to drill a 11/2-inch diameter hole, 24 inches long, in the shaft of a music stand," Ms. Andrus said.

Alumnus Westley Spruill (SB 1984) didn't know the shop existed when he was a student. "If I had, my grades would have suffered," he said. He discovered the shop about six years ago and has become an avid recreational user. "I walked in here and said 'Heaven is here and I didn't know it'," he said.

Mr. Spruill, an architect, has used the shop to build furniture, including several chairs he made during a period of unemployment which were later featured in Home Furniture, a woodworking magazine.

"It's a great place for a frustrated architect," said Mr. Stone.

Or a depressed engineer. "Anyone can enjoy building things: engineers, biologists, literature professors," said Professor Slocum, whose own end-table designs are sometimes plain and simple and sometimes intricate, with marble inlay and carving.

"It depends on how depressed I am. The level of depression is directly proportional to the amount of detail in the tables. I make something really detailed and I feel much better. I'm a 'manic-buildive' and this is great therapy," he said.

Members of the MIT community interested in using the Hobby Shop can contact Mr. Stone at x3-4343 for information about membership fees and shop hours.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on October 21, 1998.