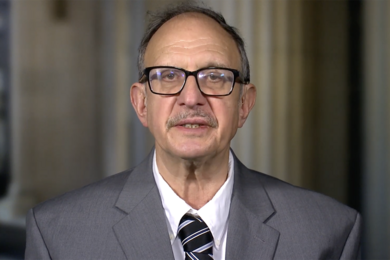

(In recognition of African-American Heritage Month, Tech Talk presents a profile of MIT's first black faculty member, Professor Joseph R. Applegate, a linguistics expert who came to the Institute in 1955 and worked on machine translation.)

In May 1956, MIT vice president and provost Julius A. Stratton issued a list of faculty promotions and appointments for the forthcoming academic year. On that list was a young African-American assistant professor of modern languages, Joseph R. Applegate.

While the list may have seemed routine enough-Professor Applegate's name appeared inconspicuously along with 45 others, indicating rank and departmental affiliation-it marked a historic event that probably went unnoticed at the time. As far as can be determined, Professor Applegate was the first black appointed to a faculty position at MIT. While there had been a handful of African-Americans in professional staff positions at MIT prior to that time, none had achieved faculty rank. Practically all of MIT's black employees were service staff-waiters, porters, cleaners, groundsmen and dormitory crew.

Born in 1925, Professor Applegate grew up in Wildwood, NJ, where his parents ran a small boarding house frequented by black entertainers such as Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. The family moved later to South Philadelphia, where he attended high school and quickly picked up Italian and Yiddish-the languages of choice in his ethnically diverse neighborhood. This early exposure blossomed into a lifelong interest in the study of languages.

Professor Applegate went on to Temple University, where he majored in Spanish and minored in German and English. After graduating in 1945, he taught Spanish and English at secondary schools in Philadelphia and became active in the teachers' unionization movement. One of the people he met through his political activities, Hilary Putnam (now a professor of philosophy at Harvard), urged him to pursue graduate work. Professor Applegate earned master's and doctoral degrees in linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania in 1948 and 1955, respectively. His PhD thesis was a formal descriptive grammar of Shilha, the Berber language of southwestern Morocco.

Professor Applegate came to MIT in July 1955 to serve on the staff of the "mechanical translation project." This project, attached to the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) and administered by Professors William N. Locke and Victor H. Yngve of the Department of Modern Languages, experimented with electronic methods of language translation. Professor Zellig Harris, chairman of the linguistics department at Penn, helped arrange Professor Applegate's appointment.

"That was part of this relationship between linguistics at Penn and machine translation at MIT," Professor Applegate recalled. "Zellig Harris and Victor Yngve had developed some kind of relationship that made it possible for Harris to say, okay, somebody is getting a doctorate at Penn in linguistics; do you have a place for that person in your machine translation project at MIT? The answer was usually yes, so there had been a steady movement of new PhDs from Penn to that project at MIT. Fred Lukoff had been there. So it was natural when we got our PhDs that this would be the job we would move into, and I was looking forward to that."

DISTINGUISHED COLLEAGUES

Other linguists with RLE at the time included Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle (now Institute Professor and Institute Professor emeritus, respectively). Like Professor Applegate, Professor Chomsky had earned his Penn doctorate in 1955; at RLE he worked on both machine translation and mathematical studies of grammars. RLE-affiliated linguists carried out a varied, vibrant research program before the establishment of linguistics as a discrete academic unit at MIT.

Professor Applegate worked for several years on mechanical translation with others in the RLE group. Following his appointment to the faculty of the modern languages department in 1956, he also taught German and intermediate and advanced subjects in "English for Foreign Students." He became director of MIT's new language laboratory in April 1959.

Also during this period, he conducted important research on language acquisition. He decoded and described the phonology of a dialect spoken by children in a black family residing in Cambridge. This study-published in Word in August 1961-concluded that the children's speech was not an imitation of the language of adults, but rather "an autonomous system with well-developed rules." Linguists often cite the study as a classic of its kind.

Although rigorous, Professor Applegate's workload at MIT was manageable in part because of the spirit of collegiality and intellectual excitement that prevailed on campus. "Jerry Wiesner was director of RLE, and Norbert Wiener was down the hall," he said. "I do recall informal conversations with Norbert Wiener, you know, just almost as casual as the time of day, but later I thought, `Oh yeah, where did I pick up that idea?' And that was the way people worked in those days. I learned a lot about computers and everything during that period, abstract theory, more or less from the informal discussions with Wiener and comments from Wiesner."

By the late 1950s, however, the mechanical translation project had not progressed as quickly as Professor Applegate and others had hoped. "We came to the conclusion that it would not be possible to develop a computer program for machine translation because we could not describe the process of translation," he said. "Until we could provide a complete description of that, we couldn't really write a computer program. There was a certain-what shall we say, not feeling of depression or anything, but sort of, 'do we really want to continue in this area?'"

This uncertainty, coupled with an offer to teach Berber languages at the University of California at Los Angeles, led to Professor Applegate's departure from MIT in 1960. He served as an assistant professor of Berber languages at UCLA from 1960 to 1966. His subsequent career took him to Howard University, where he was associate professor of linguistics from 1966-69; director of the African Studies and Research Program from 1967-69, and professor of African studies beginning in 1969.

Professor Applegate's MIT appointment stemmed from a tradition of personal ties between linguists at MIT and Penn, the institution where he earned his doctorate. It was not part of a conscious effort to recruit minority faculty and staff; the first formal efforts in this regard at MIT were still nearly two decades in the future.

GROWING AWARENESS

The five years that Professor Applegate spent at MIT, however, did coincide with a period of growing awareness of racial inequities at the Institute and, more generally, in American education. Starting about a decade earlier, there had been considerable discussion on campus about the implications for MIT of the push in the Massachusetts State House toward fair employment and fair educational practices legislation. In the early and mid-1950s, the issue of fraternities with clauses restricting entry on the basis of race or religion provoked sharp debate. A year before Professor Applegate's arrival at MIT, the US Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared "separate but equal" as unconstitutional, thus directly challenging racial segregation in academic institutions nationwide.

In March 1955, MIT hosted a three-day conference-quite likely the first of its kind held anywhere in the United States-to discuss issues of racial discrimination in higher education. The President's Office handled occasional correspondence from individuals recommending "worthwhile" black youngsters for admission.

In the midst of all this, Professor Applegate's own experience at MIT appears to have been essentially race-neutral. He did not feel singled out for special treatment, either positive or negative, because of his race. "As a member of the faculty," he says, "I don't think there was any hesitation about acceptance."

(This article draws on materials compiled for Dr. Williams's Blacks at MIT history project, including archival documents, published sources and an oral history interview conducted with Professor Applegate at Howard University in February 1996. Dr. Williams is special assistant to the president, ombudsperson, and adjunct professor of urban studies and planning at MIT. He is working on a book tentatively titled Search for Identity: A History of the Black Experience at MIT, 1865-1995. Anyone with historical information about the black experience at MIT (interesting anecdotes, personalities, events, documents, etc.) is urged to contact him in Rm 3-221, cgwm@mit.edu>, or Philip N. Alexander, research associate in the Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies, Rm 20C-109, palex@mit.edu>.)

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 5, 1997.