Hank Green, prolific content creator and YouTuber whose work has often focused on science and STEM-oriented topics, is delivering today’s OneMIT Commencement address. Green, along with his brother John, has built the educational media company Complexly, racking up over 2 billion views for the their content, including the channels SciShow and CrashCourse. MIT News talked with Green in advance of his commencement remarks.

Q: MIT’s president, Sally Kornbluth, often talks about the value of curiosity. How much of curiosity do you think is natural, or alternately, how do you keep cultivating your sense of curiosity?

A: There’s a line in my talk today, something like, if I could attribute my success to anything besides luck, it is always believing that there is no better use of a day than learning something new. And I don’t know where that came from. I feel like everybody is like that. I have an 8-year-old son and he’s like that. My wife texted me last night and said, “He wants to know what dark matter is.” Well, wouldn’t we all?

I don’t know exactly know how to cultivate that, but I do have strategies for orienting [toward] that. … The reality is that it’s very easy to orient my curiosity toward what would make me the most money or what makes me feel better than other people. I’m very aware of this as founder and host of SciShow, that people might watch because they want to feel superior to people who don’t know stuff. And that’s a motivation, and at least it’s oriented toward knowing more stuff, but it’s not the best motivation. I think one of the great powers people can have is being able to orient your curiosity around what your values are, and how you’d like to see the world change. And that’s something that I have worked a lot on.

Q: It seems like you’re not just learning about new things, but also, in the process, aren’t there a lot of new challenges in figuring out how to communicate things best?

A: Tons! I mean the thing about it is that the communications landscape changes very fast. Five years ago, TikTok wasn’t really a thing. When I heard about it, I thought, “You can’t do science communication in a minute. That’s impossible. All you can do is dance videos.” And then I saw people doing it and said, “Well, you can.”

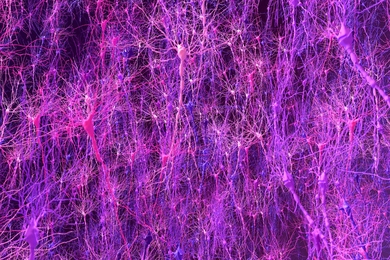

I’m also working on a book-length science communication project right now. When I say book-length, it’s a book about the biology of cancer. And that process, it doesn’t end there, but for me that’s the largest, longest communication you can do.

[But alternately] my friend Charlie made one of the first science TikToks I saw. It’s a skit about how vaccines work, where one character was a vaccine and one was an immune cell. That was probably 30 seconds long and it’s probably better than any way I would have communicated about vaccines in the midst of the Covid epidemic on the new platform, pre-bunking fear about vaccines from the very beginning, very simply explaining what they are in a way that’s very accessible and not going to turn anybody off.

Q: What are you talking about in your remarks today?

A: Yeah, I mean we are in a super-weird moment with regard to the amount of power humanity has. We’ve been in moments like this before, where the amount of power at our fingertips increases exponentially very quickly. The nuclear age is the big one in terms of the speed of that change. But it feels like biotechnology and AI and communications are all adding up to being a really big deal.

The thing I kept coming back to was — I didn’t put this in the talk, but it inspired the talk: Okay, so we had a period of time where humans powered the world through muscle. And now human muscle is not the [most] important part of how we build. Intelligence and dexterity are important, but in terms of calories expended, [that’s done] by machines. If we end up in a world where that [also] becomes more the case for intelligence, what do we still have a monopoly on? A lot of people would still answer that question with “Nothing,” I guess.

I think that’s really wrong. I think we’ll still have a near-monopoly on meaning, and what we mean to each other. So, what I wanted to get at is, all the stuff that we do, all the things that we build, at the root, the base, we do it for people in some way. It might be a playlist for your friend, or the Human Genome Project, but all of that, we’re doing for people. And so keeping [ourselves] oriented toward people, and not building around them as an obstacle but building for them, is the thing I’ve wanted to be focused on.